Special Issue, April 2016: Exploring the Frontiers of Digital Gaming

MATHIAS FUCHS

Leuphana University

Abstract

This article traces back a games-related phenomenon that is currently called gamification, but has been known, theoretised about, used, misused and exploited avant la lettre. The notion of gamification is often said to have been coined in 2002 by Pelling and popularized in the 2010s by Deterding, Khaled, Dixon and Nake, McGonigal, Zichermann and others. There are, however, precursors to the idea of our society being permeated by games. This article presents examples for gamification from the second half of the 18th century, before the term gamification even existed, and refers to ideas brought forward by Tersteegen, Kirnberger, Bernoulli, and others.

Keywords: gamification, ludification, lottery, Spielsaeculum, eighteenth century

Résumé en français à la fin du texte

“The century that we live in could be subsumed in the history books as . . .

the Century of Play“

(Daniel Bernoulli, 1751)

This article traces back a games-related and allegedly brand-new phenomenon that is called gamification, but has been known, theorised, used, misused and exploited avant la lettre. The notion of gamification is often said to have been coined in 2002 by Pelling and popularized in the 2010s by Deterding, Khaled, Dixon and Nake (2011), McGonigal (2011), Zichermann (2011), and Werbach and Hunter (2012). There are, however, precursors to the idea of our society being infiltrated, revolutionised or spoiled by play. I will present examples for gamification before the word even existed and will refer to ideas brought forward by Gerhard Tersteegen, Johann Philipp Kirnberger, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Mozart, Daniel Bernoulli, the Roentgens, and others. The focus of the historical comparison is on the second half of the 18th century.

The hypothesis is that gamification is not exclusively linked to digital cultures and that processes that can with good reason be compared to and called gamification are constituted by human playfulness in the context of various constellations of historic and economic settings. Rococo game craze (ludomanie) and the impact of Lotto di Genova on 18th century society can be compared to the hyped monetary expectations resulting from gamification and the social phantasms created in our contemporary context. Eighteenth century and twenty-first century ludofetishism (and jeu pathologique) will be analysed as particular forms of zeitgeist and lifestyle. Musique aléatoire by the successors of Marcel Duchamp will be critically rethought with a look back on aleatoric composition and the ludification of music in the second half of the 18th century.

Economic Drivers[1]

If we believe what renowned US-American market analysts tell us unanimously, then we have to accept that nothing will influence our lives as much as these: mobility, social media and gamification. The latter is said to have the strongest impact. “Gamification is projected to be a $1.6 billion market by 2016“ (Corry 2011). Other sources predict $2.8 billion for 2016 (Palmer, Lunceford, and Patton 2012) and $5.5 billion for 2018 (Markets and Markets 2013). In 2011 marketing analyst Gartner said “by 2015 more than 50 per cent of organizations that manage innovation processes will gamify those processes” (Gartner 2011). Yet one year later Gartner said: “Gamification is currently being driven by novelty and hype. By 2014 80% of gamification applications will fail to deliver” (Fleming 2012). But irrespective of whether gamification will change little, something or everything, no one can deny that it became a buzzword that describes what many fear or hope to happen right now. The process of a total permeation of our society with methods, metaphors, values and attributes of games (Fuchs 2011, 2013)[2] has been baptised gamification in 2002 (Marczewski 2012) and has since then been popularised by US marketing companies and their respective PR departments. Even though there have been attempts to differentiate between games-related and play-related phenomena, or by processes that could be seen as either driven by ludus or paidia (Caillois 2001/1958), gamification has remained the buzzword. Greek, Italian, Spanish, Swedish and German terminological creations have been introduced and discussed in the scholarly world, but neither παιγνιδοποίηση, ludicizzazione, ludificação, gamificación, ludización nor the German-Latin ludifizierung could compete with the Anglo-American gamification. The reason for this might be that the Californian league of gamification evangelists such as Zichermann (2011), McGonigal (2011) and company have already been sowing on the semantic field at a time when European game scholars were not quite sure whether the ludification they observed was more of a curse than a gift. Flavio Escribano’s terminological creation of a “ludictatorship” points in that direction (Escribano 2012).

The US politician Al Gore did not seem to be worried about what gamification might bring to our society when at the 8th Annual Games for Change Festival in June 2013 he declared: “Games are the new normal”. On the one hand this seems to be the Democrat’s or even the democratic assumption that everybody should have the right to play. On the other hand, it declares total play with the hidden implication that those who cannot play society’s games and those who do not want to play them are not to be considered normal. Even though 2002 is usually said to be the year when the term gamification was coined, it was only around the beginning of this decade that gamification became a buzzword. Deterding, Dixon, Khaled and Nacke (2011), Schell (2010),[3] Reilhac (2010)[4] and others presented different flavours of gamification, some of them design-oriented, others psychological or judgemental. For Sebastian Deterding and his colleagues

it is suggested that ‚gamified’ applications provide insight into novel, gameful phenomena complementary to playful phenomena. Based on our research, we propose a definition of ‘gamification’ as the use of game design elements in non-game contexts (Deterding et al. 2011).

All of the definitions of gamification that have been proposed since 2002 are based on the idea that the digital computer and digital computer games are a reference without which gamification could not be conceived. There are, however, predigital predecessors of gamification long before digital computers became popular. A decade before programmable computers such as the Z3, Colossus or the ENIAC were introduced, a playful labour attitude had been mentioned and praised by the author Pamela Lyndon Travers. As early as in 1934 Travers rhymed for her Mary Poppins Character:

In ev’ry job that must be done

There is an element of fun

You find the fun, and snap!

The job’s a game! (Travers 1934).

This is obviously what we would nowadays call the gamification of labour. It is precisely the use of game elements in non-game contexts, as the definitions of Zichermann, Reilhac, Schell, Deterding et al. suggest.

This article intends to present examples for gamification avant la lettre and compares these predigital forms of ludification with recent approaches that build heavily on the historic ideas, concepts and gadgets. In particular the following fields of predigital gamification will be looked at: religious practice, music, magic, education, lifestyle and styles for killing.

- Gamifying Architecture, Furniture and Lifestyle in the “Century of Play”

In 1751 Daniel Bernoulli tried to catch the Zeitgeist of his century by saying: “The century that we live in could be subsumed in the history books as: […] the Century of Play“ (Bauer 2006, 377).[5] Bernoulli expressed an observation about the gamification of lifestyle that was based on observations in Vienna, but was valid for the main European capitals like Paris, Rome, London, Den Haag, Rome and Naples. The gaming culture was a pan-European phenomenon based on widely distributed types of games and game rules. L’Hombre, e.g., a game of cards that was originally developed in Spain, then picked up by Maria Theresia, the wife of Louis XIV, and was within a few years played in all European countries with a few local variations only.[6] This made it possible for a new travelling social class that extended beyond aristocracy to engage in gaming as a European lingua franca. Frequent travellers such as Mozart or Johann Wolfgang von Goethe could expect to find a gaming community in almost every city in Europe that they could share experiences and social skills with. Hazardous games or jeux de contrepartie, such as the Pharo game or Hasard were temporarily banned in certain regions, but by the mid-18th century it became common practice to play these games in private and in public places.

Instructions for games like the mid-18th century “Pleasant Pastime with enchanting and joyful Games to be played in Society” (Bauer 2006: 383)[7] were translated into most of the European languages and became popular amongst people of different social classes (Bauer 2006, 383). Lotteries could be found everywhere and became a source of income for some and a serious economic problem for others. Pope Benedict XIII’s threat of excommunication for lotto players in 1728 started a controversy about the legality and piety of gaming practices. Benedict XIII was also known to have limited the use of wigs and luxury suits. The pope’s fierce standpoint that threatened players and lottery providers alike with excommunication and galley slavery started a dynamic process of prohibition, punishment, and increasing acceptance of public lotteries in most European countries including the Catholic countries. (Krünitz 1807, 124)

A few years after Benedict XIII’s verdict the lotto-friendly attitude of his successor, Pope Clement XII, helped reinstalling lotteries. Clement XII, who was elected in July 1730 at the age of 78, conceded to legalize commercial gaming in 1731, if the profits would exclusively be used for helping “young unmarried women with children”. The revenue from the lotteries was, however, also used to finance a series of new projects, the main one being the new façade of S. Giovanni in Laterano.

Pius VI in 1785 finally fully installed lotteries for commercial purposes and used the revenue for various works of piety or profane interest, e.g. to buy back real estate. The lottery profits were deposited in Depositeria General, at the free disposal of the pope who, at its discretion, spent the money for purposes such as the reclamation of the Pontine marshes.

With a small number of isolated attempts to organise huge lotteries in the 16th and 17th century in non-papal terrain, the late 17th century saw London, Utrecht und Amersfoort staging huge public lotteries to state public expenses and for private profit making. The Amersfoort lottery is said to have sold 16.000 lots and it took longer than 4 weeks.[8] The top price amounted to 75000 guilders, and the city made a total profit of 30000 guilders, which has been said to be “little in total, but considering the enormous popularity of the event that attracted visitors from various places, all accomodation has been rent out and enormous profits have been made”[9]> (Zedler 1791). With the beginning of the 18th century lotteries became completely legal and developed into a popular cultural phenomenon that changed leisure behaviour of a wide range of social groups and created a pan-European gambling industry.

In 1751 Empress Maria Theresia introduced a lottery called “Lotto di Genova” with 90 numbers to choose from and put the rights to run the business on auction. Earl Cataldi bought the privilege to exploit the lottery business and on 21 November 1752 the drawing of lots started at Vienna Augustinerplatz. In the German city of Braunschweig Duke Karl I started a lottery in 1771 with 50 drawings of lots per year. Three years later the traditional banking Haus Barara & Comp started investing in the gambling business and made a fortune from that.

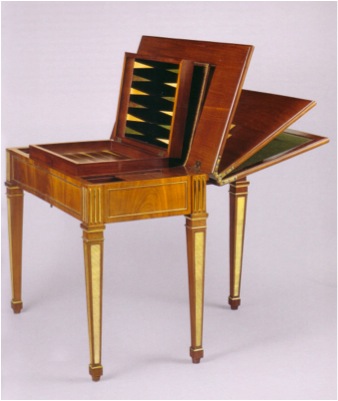

The 18th century was also the time when “apartements pour le Jeu”, i.e. play rooms, were introduced in the houses of the aristocracy as well as in houses of the bourgeoisie. Special furniture to display popular games or to hide less appreciated games from the eyes of the visitors was designed.[10] Abraham Roentgen (1711-1793) and his son David Roentgen (1743-1807) from the German region of Neuwied have arguably been the most successful furniture designers of their times. They were design superstars and fashion celebrities that produced for the courts of France, Prussia and Russia, and they made their international success by gamifying furniture (Koeppe 2012). The products of the Roentgen luxury brand created profits that equalled those of the porcelain manufacture of Meissen. Hidden drawers, portability, technically advanced mechanisms and playful, multi-referential artwork made the cabinets, tables and desks play-furniture par excellence. The game table they produced in the 1780s could be dismounted and transported easily (Fig. 1). Multi-hinged tops demonstrated a profound knowledge of French and English cabinet technology, and marquetry à la grecque served not only as decoration but as a visual statement of the owner of the table that he was well versed in history and mythology and that he was educated in a European esprit that was rich of cultural references across centuries and borders.

Of course high-tech games-gear of this kind was not inexpensive. Not only was the price of the piece of furniture high, but maintenance contracts had to be bought as well to keep the gamified table in shape. David Roentgen offered a contract as “artiste-ébéniste et machinist du prince” for one of his devices. This contract consisted of periodic check-up and even updates of the machine. (Koeppe 2012, 9)

Fig. 1.: Game table by David Roentgen (ca. 1780-83). Oak and walnut, veneered with mahogany, maple, holly, iron, steel, brass and gilt bronze. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The table met a demand of upper- and middle-class houses, when dicing and playing cards, chess and backgammon had become widely popular (Koeppe 2012, 163). The Roentgens reached out to ambitious middle-class clientele, but were eager to market the brand through commissioned work for the extravagant members of the royal courts in Versaille, Potsdam and Petersburg. Following a business model introduced by Dutch cabinet makers, the Roentgens started selling their expensive items at furniture lotteries. These events met the aristocracy’s love of gambling and created publicity for Roentgen products at the same time (Koeppe 2012, 8).

The way the gamification of social lifestyle changed from the 17th to the 18th century was via increased availability, trans-European distribution channels, and an esteem of playfulness that transcended class and social group. It is for this reason that Bernoulli’s proposition to call the 18th century the “Century of Play” makes a lot of sense. Having said so, Bernoulli was not able to see how another wave of gamification would change another century: the 21st century is about to repeat the games craze of the 18th century. Today we see ubiquitous availability, trans-planetary distribution channels, and an acceptance of computer games that transcends class and social group, and games do not any longer belong to an age group, ethnicity, gender or subculture.

- Gamifying Religious Practice

Gods from antique Greek myths knew how to play tricks on each other. Indian avatars experienced lust and joy and even the warrior gods from Nordic mythology had a lot of fun every now and then. The Loki character from Edda is a joker and a jester. Little fun however has been reported from the Christian god, son of god or the corresponding spirits. Protagonists in Jewish-Christian mythology never laugh, never make love, and they rarely play. Einstein is said to have commented on God’s resistance to play with his famous phrase of “God doesn’t throw the dice”. If playing or gambling is reported of in the bible, it is usually the bad guys who do so. The maximum offence against piety and the example par excellence of how not to behave in the vicinity of Christ are the soldiers at the cross who dare to play when Christ is dying. Completely in line with the negative sanctioning of playfulness is the prohibition of any gambling practice in Christian culture. Play, that was felt to be the pastime of the Gods in other religions, was rather associated with the devil in Christianity. Who could have invented such a nuisance as play? Reinmar von Zweter, a poet from the 13th century had no doubt about that when he wrote in a truly Christian spirit: “The devil created the game of dice”:

Der tuivel schouf das würfelspil,

dar umbe daz er selen vil

da mit gewinnen will (Wolferz 1916).

His anger about dice games is actually exemplifying a much wider rejection of play in general. Almost every century in Western European history knows about legal sanctions on gambling, prohibition of certain games and of violent destruction of games (Ritschl 1884). On 10th August of 1452 Capistrano, a sermoniser from the city of Erfurt in Germany was said to have collected games that he labelled “sinful luxury items” and piled them up to an impressive mountain of 3640 board games, some 40,000 dice games and innumerable card games. The games have then been burnt publicly (Dirx 1981, 82).[11]

It is frightening to see that game burning preceded book burning and that in both cases it was not the medium that was intended to be destroyed but a cultural practice and a practicing group.

In Western Europe gambling that involved monetary benefits was often prohibited. Reports about public houses that were accused of being gambling houses were used in many cases to shut down the pubs or to penalize the innkeepers. A class action from 1612 in Ernsdorf united the village mayor and members of the parish choir to sue an innkeeper who served alcoholic drinks in order to “attract gamblers and scallywags to visit his inn” (Schmidt 2005: 255).[12] In 1670 a list of all the inhabitants that were suspected of playing games was posted in the very same village of Ernsdorf. Nine years later the court usher was told to withdraw bowling pins from children on the day of their catechism classes (Ibid).

Yet real politics within Christian ethics developed ways and means to play and be pious at the same time. Already in the 1ate 17th century there have been board games based on religious instruction and learning. Young Protestant women who have been converted to Catholicism after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes were introduced to the ethics of their new conviction via a game that was called “L’Ecole de la Vérité pour les Nouveaux Convertis”.[13] The game, based on a variation of a jeu de l’oie, held gameplay information that delivered messages to the players that clarified who is right and who is wrong. On the side of the good ones Louis XIV featured as “Louis Le Grand”, and if the player was lucky enough to hit field 35, the place where Louis resided, she would proceed to field 59 directly: Jerusalem.[14] Less lucky were those who happened to arrive at field 11, the pulpit of pestilence, that was described in the game as the very location of the “spirit of fallacy”.[15] Games as propagandistic tools for Catholic or Protestant interests have been reported to be in use publicly or in a clandestine way by the end of the 17th century.[16] Gerhard Tersteegen can be called an 18th century gamification expert for religious practice. His Pious Lottery[17] was a card game consisting of 365 cards that contained words of wisdom and advice for the believers. By randomly selecting a card from the deck of cards the pious gambler would perform two activities at the same time: playing an aleatoric game of cards and practicing Christian-minded devotion. Tersteegen’s gamified prayer book was successful because of the popularity of profane lottery practice of the 18th century that his game appropriated and adapted for Tersteegen’s own purposes. The sermonist announces his game as a lottery with no danger of losing. If however, you hit the jackpot (“drawing the best lot”) your price will be unsurpassable:

This is a lottery for Believers,

and nothing can be lost,

Yet nothing would be better,

than drawing the best lot (Tersteegen 1769, title).[18]

Not everybody was happy with Tersteegen’s ludification of serious content. One of his contemporaries and critics, Heinrich Konrad Scheffler, mocked the pious lottery in his essay from 1734 on strange religious practice: “Praxis pietatis curiosa” (Brückner 2010, 261) as not pleasing to God.

The itinerant preacher Tersteegen was faced with a problem that is not unlike today’s problems of selling products with low use-value as desirable – or boring work as fun. Common 18th century practice of prescribing a prayer per day must have been extremely fatiguing for the average believers. When the radical pietist Tersteegen introduced alea (Caillois 2001/1958) he achieved what today’s gamification evangelists try to accomplish: increase customer loyalty via fun elements. “Gamification is Driving Loyalty“ (Goldstein 2013), “Motivation + Big Data + Gamification = Loyalty 3.0” (Paharia 2013), “Gamification = Recognition, Growth + Fun” (DeMonte 2013). More than 200 years before the notion of gamification had been introduced, similar practices were already in use: establish loyalty by hiding the primary company’s goal and offering “peripheral or secondary mechanics” (Ciotti 2013) that establish pseudo goals and re-direct the attention of the customers aka gamers.

- Gamifying Music and Dance

Contemporary to Gerhard Tersteegen, Johann Philipp Kirnberger, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach and Maximilian Stadler worked on something that could be called the gamification of music[19] when introducing a ludic generator for musical composition.[20] Kirnberger’s Ever-Ready Minuet and Polonaise Composer[21] was first published in 1757 and then again in a revised version in 1783. The game preceded the Game of Musical Dice[22] from 1792 that has dubitably been attributed to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. If Mozart was the author of the Musikalisches Würfelspiel, his intention was most likely to present and sell another virtuosity stunt and not to question the nature of composition. It is probably also fair to say that Mozart was not particularly hesitant in appropriating material and concepts from fellow composers and to polish them in his personal way to make them a successful commodity. The idea of Kirnberger’s gamified system of composition as well as that of Mozart’s was to propose that music could be conceived as a game that follows certain rules and is affected by an element of chance, or alea – as Caillois would name it (Caillois 2001/1958). This idea is completely anti-classical and anti-romantic, but was epistemically coherent with the 18th century thought. It is therefore not surprising that systems like the Ever-Ready Minuet and Polonaise Composer, or the Musical Dice have been devised by various 18th century composers.

In 1758 Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach’s A Method for Making Six Bars of Double Counterpoint at the Octave Without Knowing the Rules[23] introduced a game for short compositions as a demonstration of method and a tool for rule-based composition. It would not be appropriate to criticize Johann Sebastian Bach’s son for a mediocre quality of the counterpoint compositions produced. The compositional spirit of the 18th century was different to classical musical thinking and for a late Baroque composer the main achievement was to produce as effective as possible what fitted the rules of musical craftsmanship. Aesthetic subtlety was not the point then.

Maximilian Stadler was another composer who worked with a set of dice. His Table for composing minuets and trios to infinity, by playing with two dice[24] was published in 1780 and might well have been the inspiration for Mozart’s Würfelspiel. Stadler was friend to Mozart, Haydn and Beethoven and it would not be too surprising if Mozart had picked up a few ideas from Stadler when meeting in Vienna. Innovative ideas were not copyright protected at the time of Mozart, and Mozart was reported to have appropriated material, ideas and concepts from fellow composers. But it is also possible that Haydn, another friend of Stadler’s, might have influenced Stadler, Mozart or both of them when presenting his Game of Harmony, or an Easy Method for Composing an Infinite Number of Minuet-Trios, Without Any Knowledge of Counterpoint[25] that was published in 1790 or in 1793 in Naples by Luigi Marescalchi. The piece that is said to have been written in the 1780s, is very close in concept and terminology to Stadler’s Table. À la infinite is what Stadler had in mind and Haydn, if he really wrote the Gioco himself, refers to as “infinito numero”. Once more, it was the easy method – maniera facile – that served as key motivation for composers of the 18th century to use gamification for the compositional process.

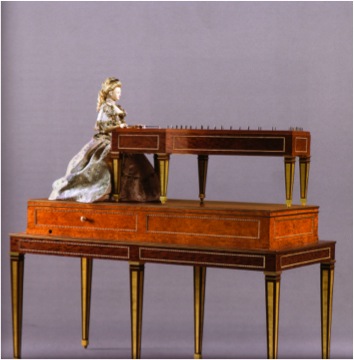

The gamification of music was on one hand implemented in the software of music production, i.e. generative algorithms, but it was also inscribed into the hardware of the time. Playful musical automata have been constructed by Jaquet-Droz and David Roentgen and have been enjoyed by the aristocracy, men and women from various social groups and been discussed by philosophers, pious scholars and poets. Roentgen’s la Joueuse de tympanon has been delivered to the court of Louis XVI in December of 1784 and created a huge wave of discussion about human soul, automata and playfulness (Koeppe 2012, 146). Marie Antoinette found it appropriate to have the android assessed by members of the Cabinet de l’ Académie des Sciences in 1784 before using it for her amusement.

Fig. 2.: Automaton of Queen Marie Antoinette, called la Joueuse de tympanon (The dulcimer player) by David Roentgen (1784). Mahogany, thuja burl wood, oak, ivory, textiles, brass and iron. Musée des arts er metiers, Paris.

Leonard Meyer observes that the practices of aleatoric and ludic methods in musical composition and in musical performance are for good reasons present in the 18th century but hard to find in the 19th century musical practice:

“Eighteenth-century composers constructed musical dice games while nineteenth century composers did not . . . [W]hat constrained the choice of figures were the claims of taste, coherent expression and propriety, given the genre of work being composed, rather than the inner necessity of a gradually unfolding, underlying process [as in nineteenth century music]” (Meyer 1989, 193).

I would argue here that gamification provides methods for coherence and propriety in the context of music – as has been demonstrate by Meyer –, but also in other contexts such as design (compare the section above), religious practice (compare the section above) and dance. That is why the 18th century is a time when examples of predigital gamification can be found in many cases. Processes that are driven by gradually unfolding underlying structures are much harder to be gamified. The ludic turn of the 18th century became apparent not only in the passion for games, in ludified social manners, in religious practice or in music. It also shaped the way people used to dance then. In her “Sociology of Dance on Stage and in Ballrooms”, Reingard Witzmann notices that dance was conceived as a game in Mozart’s Vienna. At the end of the last act of Le Nozze di Figaro Mozart calls the actors of Le Nozze to reassemble on stage and proclaim what could be called the motto of the century: “Sposi, Amici, al Ballo, al Gioco!” (Witzmann 2006, 403).[26]

- Gamifying the Magic Arts

In 1762 Wolfgang Schwarzkopf published a book in the German city of Nürnberg that presented an enlightened and new take on what formerly has been said to be black magic or pre-modern sorcery. Schwarzkopf subtitled the book Playground of rare Sciences[27] and combined a description of mathematical and mechanical skills with essays about card games, dice games and an encyclopaedic section of prestidigitator tricks. This book was one of many scientific attempts of the 18th century to reclaim magic and enchantment as playful activities – and to separate it from any connotations to diabolic and irrational activities. In their book Rare Künste, Brigitte Felderer and Ernst Strouhal lay out how the cultural history of magic took a dramatic turn in the 18th century and abandoned medieval black magic in favour of a ludic activity (Felderer and Strouhal 2006). This new form of edutainment was based on an enlightened concept of popular science, socially embedded empirical research and a post-religious belief in the fact that the new type of magic had much more in common with science then with ritualistic or obscure practices from the past. As James George Frazer put it in his Golden Bough:

Magic is much closer to Science than it is to Religion. Different to what religion tells us, Magic and Science both are based on the presupposition that identical causes result in identical effects (Frazer 1989, 70).

As a consequence, it made a lot of sense for the 18th century publisher to talk about “natural magic” – as Schellenberg did in 1802[28] – or “the magic of nature” – as done by Halle in 1783.[29] The reappearing pattern of legitimation for the act of talking about magic as a game and as science is the rhetoric figure that magic is useful in societal daily life and that it is entertaining: “Revised to Take Account of Entertainment and Serious Applications“ (Halle in Huber 2006, 335) or “Useful for Social Life” (Schellenberg, ibid). This line of argumentation can be followed via Goethe’s bon mot of “scientific games like mineralogy and the likes”[30] (Kaiser 1967, 37) up to the present.[31] This is probably not the place to develop the idea, but I would speculate that the notion of serious games can be followed back to the 18th century programmatic efforts to declare magic as a game, and do so in introducing the idea that science can be entertaining and that entertainment can be scientifically relevant. Today we call this project edutainment.

There are two points I want to make here by putting examples from the magic arts, furniture design, and music and dance in close vicinity to the gamification of religious practice of the very same decades:

- I’d like to propose a concept of gamification as “permeation of society with methods, metaphors, values and attributes of games” (Fuchs 2011, 2013) as opposed to the idea that gamification can fully be understood as the transfer of game design elements to non-game contexts with no regard to the historical and social framing. The latter is symptomatic for most of the scholarly attempts to define gamification (Deterding et al. 2011[32], Schell 2010[33], Werbach and Hunter 2013). If I understand Deterding, Dixon, Khaled and Nacke, Shell, Werbach and Hunter correctly then a single instance of adapting game design elements for non-game contexts could qualify as gamification. I differ from understanding gamification that way and would be extremely hesitant to theorize societally isolated actions like convenience store marketing or flight sales optimisation as relevant for the phenomenon of gamification, if they are detached from a historical view and a social perspective that includes cultural analysis on a global scale.

The way I want use the notion of gamification is in line with various “fications“ and “izations“ that have been introduced in the social sciences during the past 20 years. Globalization (Robertson 1992, Ritzer 2011), McDonaldization (Ritzer 1993), Californication (Red Hot Chilli Peppers 1999),[34] Ludification (Raessens 2006), Americanization (Kooijman 2013) or Disneyfication (Bryman 1999, Hartley and Pearson 2000) are all based on the assumption that we observe large societal changes that are driven by apparatuses that influence various sectors of society at a time. Of course, McDonaldization cannot be attributed to a society just by spotting a few fast-food restaurants in countries other than the USA. It is a way of living based on an economic structure, a power structure, a number of neologisms and changes in spoken language, introduction of a set of manners and habits and a perceptual shift, that make McDonaldization what it is (Kooijman 2013). I would in analogy claim that “game design elements applied to non-game contexts” do not make a society gamified. It is the permeation of many societal sectors with methods, metaphors and values that stem from the sphere of play that produce gamification.

- I want to show here that certain historical constellations have been a fertile breeding ground for the process of predigital gamification. The second half of the 18th century certainly was one of those. The intention is also to explain why certain moments in history lent themselves to foster gamification, and to propose a few good reasons why our decade seems to be one of those as well.

Conclusion

This article cannot provide the reader with a complete history of gamification and gamification-related historical documents, to prove that something that we call gamification now has happened in former centuries already. I also cannot sum up all of the possible differences that might exist between games of former centuries and computer games of our days. My main hypothesis is though, that we can detect similarities in aspects of games hype, games craze, the seriousness of games, and of a process that transforms non-game contexts into playgrounds for ludic activities and of ludic experience across centuries. Such playgrounds could once be found in learning, religious practice, music, magic, dance, theatre and lifestyle. Such playgrounds for ludic activities can equally well be spotted nowadays, when we look at theatre theory and find “Game Theatre” (Rakow 2013), when we look at religious blogs and find “Gamifying Religion” (Toler 2013), when we look at the information from Health services and find “Fun Ways to Cure Cancer” (Scott 2013) or “Dice Game Against Swine Flu” (Marsh and Boffey 2009), or when we investigate collective water management and find “Games to Save Water” (Meinzen-Dick 2013).

It is the width of applications and not the individual example that support the hypothesis that gamification takes place as a global trend, a new form of ideology, or as a dispositif – if you want so. This is not exclusively dependant on the digitalisation of society or the massive economic success of computer games. What I have tried to demonstrate here, is a historic perspective on an understanding of gamification as a way of living (and dying), making music, selling and buying, engaging in economic processes and power structures, communicating and introducing new manners and habits for a decade or a whole century. This can be the decade of the 2010s, but it can also be the 18th century, the “Century of Play” – “Spielsaeculum” – as Bernoulli called the century he was living in in 1751.

The second half of the 18th century shared “pragmatic-relevant networking” (Lachmayer 2006, 35) with our days. The contemporaries of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Schikaneder, Tersteegen, Casanova, Bernoulli, Schwarzkopf and Stadler were deeply involved in a European “supra-nationality” (ibid) that assembled a multiplicity of languages, styles, games and sources of knowledge that somehow resembles our world wide web – without being worldwide then. Still powered by the naivety of a desire for unfiltered access to a variety of scientific, semi-scientific, popular or superstitious forms of knowledge, the enlightened and the not so enlightened ones of the 18th century were striving for visions of progress. Playfulness on a personal level that included mimesis, alea and ilinx (Caillois 2001/1958) was a driver for caprice and virtuality rather than flat realism. The ludicity of the times was conductive to multi-faceted identities and strictly contradictory to a monosequential development of character and career that later centuries requested as a prerequisite for social inclusion. It might be that we have returned to the state of a Mozartesque playfulness and that the gamification of our society sets up a scenario for an intelligent plurality of expression, experience and knowledge at a global level. Not completely serious, but myth-making and myth-breaking at the same time.

It might, however, also be true that our decade resembles the second half of the 18th century in a way that Doris Lessing once described with these words: “This country becomes every day more like the eighteenth century, full of thieves and adventurers, rogues and a robust, unhypocritical savagery side-by-side with people lecturing others on morality“ (Fielding 1992, 762). Rococo culture developed a style that was jocular, florid and graceful and at the same time full of sophisticated coarseness. And is this not identical to the state that our discourse on gamification is at? We want to be SuperBetter and want to enjoy “self-expansion escapism” (Kollar 2013). We are slightly worried about it and we speculate about a forthcoming “Revolution” (Zichermann 2013), yet we shout out loudly “Gamification is Bullshit!” (Bogost 2011). We finally discover that “gamification is transforming our world, contaminating it like never before” (Reilhac 2010). Isn’t this very much an expression of Neo-Rococo identity?

In due consideration of the striking similarities of 18th century ludification and the gamification phenomenon we encounter today, one has to concede that there are differences in what makes a society a ludic society then and now. This article intends to shed light on complementarities and structural differences of gamification at present and in the past. The analytical approach is based on a comparison of rhetorics, the technological basis and material infrastructure of gamification – now and in former centuries. A differentiation of “gamifications” points out that there are differences in technology, state of mobility of the respective cultures, differences in the speed of dissemination and in a new form of governmentality (Foucault 2004). All of these factors contribute to different perceptions of a phenomenon that shares a lot of features: gamification might in our days be and might in the late 18th century have been the most prominent method, metaphor and toolset for processes of the power-knowledge relationship and for technologies of the self.

Works cited

BOGOST, Ian (2011). “Gamification Is Bullshit! My Position Statement at the Wharton Gamification Symposium.“ Ian Bogost Blog, August 8. http://www.bogost.com/blog/gamification_is_bullshit.shtml.

BOURDIEU, Pierre (1980). Le Sens pratique, Minuit.

BRÜCKNER, Shirley (2010). “Losen, Däumeln, Nadel, Würfeln.” In Spiel und Bürgerlichkeit. Passagen des Spiels I, edited by Ernst Strouhal and Ulrich Schädler. Wien, New York: Springer.

CAILLOIS, Roger (2001 [1958]). Man, Play and Games. Urbana: University of Illinois.

CIOTTI, Gregory (2013). “Gamification and Customer Loyalty: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly.” Help Scout, May 1. https://www.helpscout.net/blog/gamification-loyalty/.

CORRY, Will (2011). “Games for Brands Conference, Launching I London on October 27th. » TheMarketingblog Extra, September 11. http://wcorry.blogspot.de/2011_09_11_archive.html.

D’ALLEMAGNE. Ca (1690). L’Ecole de la Vérité pour les Nouveaux Convertis. Paris: Jollain.

DEMONTE, Adena (2013). “What Motivates Employees Today?” Accessed February 25, 2014. http://badgeville.com/what-motivates-employees-today/.

DETERDING, Sebastian, Dan DIXON, Rilla KHALED and Lennart NACKE (2011). “From Game Design Elements to Gamefulness: Defining Gamification.” In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments, 9-15. New York: ACM.

ESCRIBANO, Flavio (2012). “Gamification as the Post-Modern Phalanstère“ In: Zackariasson, Peter & Timothy L. Wilson (eds.) The Video Game Industry. London: Routledge

FELDERER, Brigitte and Ernst STROUHAL (eds.) (2006). Rare Künste. Vienna, New York: Springer.

FLEMING, Nic (2012). “Gamification: Is It Game Over?” BBC, December 5. Accessed January 9, 2014. http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20121204-can-gaming-transform-your-life.

FOUCAULT, Michel (2004). Naissance de la biopolitique: cours au Collège de France (1978-1979). Paris: Gallimard & Seuil.

FUCHS, Mathias (forthcoming 2016). “Subversive Gamification.” In Playing the System: The Playful Subversion of Technoculture, edited by Daniel Cermak-Sassenrath, Chek Tien Tan and Charles Walker. Singapore: Springer.

FUCHS, Mathias, Sonia FIZEK, Niklas SCHRAPE and Paolo RUFFINO (eds) (2014). Rethinking Gamification. Lüneburg: meson press.

FUCHS, Mathias (2013). “Serious Games Conference 2013: Erfolgreiches Comeback Nach Einjähriger Pause.” Accessed February 27, 2014. http://www.biu-online.de/de/presse/newsroom/newsroom-detail/datum/2013/03/13/serious-games-conference-2013-erfolgreiches-comeback-nach-einjaehriger-pause.html

FUCHS, Mathias (2011). Ludification. Ursachen, Formen und Auswirkungen der ‘Ludification’. Potsdam: Arbeitsberichte der Europäischen Medienwissenschaften an der Universität Potsdam.

GARTNER (2011). “Gartner Says By 2015, More Than 50 Percent of Organizations That Manage Innovation Processes Will Gamify Those Processes.” Accessed January 9, 2014. http://www.gartner.com/newsroom/id/1629214.

GOLDSTEIN, Mark (2013). Reinventing Loyalty with Gamification. Accessed March 31, 2014.

http://de.slideshare.net/gzicherm/mark-goldstein-gamificationpresto.

HUBER, Volker (2006). “Magisch-Bibliographische Erkundungen.” In Rare Künste, edited by Ernst Strouhal, and Brigitte Felderer, 313-338. Vienna, New York: Springer.

KOEPPE, Wolfram (2012). Extravagant Inventions. The Princely Furniture of the Roentgens. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, distributed by Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

KOLLAR, Philip (2013). ”Jane McGonigal on the Good and Bad of Video Game Escapism.” Polygon, March 28. http://www.polygon.com/2013/3/28/4159254/jane-mcgonigal-video-game-escapism.

Krünitz, D. Johann Georg (1807). D. Johann Georg Krünitz’s ökonomisch-technische Encyklopädie oder allgemeines System der Staats-, Stadt-, Haus- und Landwirthschaft, und der Kunstgeschichte in alphabetischer Ordnung. Ed. by Heinrich Gustav Flöge. Berlin: Buchhandlung des Königs. Preuß. Geh. Commerzien-Rathes Joachim Pauli.

LACHMAYER, Herbert (2006). Mozart. Aufklärung im Wien des Ausgehenden 18. Jahrhundert, Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz.

MARCZEWSKI, Andrzej (2012). Gamification: A Simple Introduction & a Bit More. Self Publishing.

MARKETS AND MARKETS (2013). “Gamification Market.” Accessed January 9, 2014. http://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/gamification-market-991.html.

McGONIGAL, Jane (2011). Reality Is Broken. Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World. New York: Penguin.

MEYER, Leonard (1989). Style and Music: Theory, History, and Ideology. Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press.

MOSCA, Ivan (2012). “+10! Gamification and deGamification.” In GAME 1(1). http://www.gamejournal.it/plus10_gamification-and-degamification/#.UwtTd_R5OA8.

NIERHAUS, Gerhard (2009). Algorithmic Composition: Paradigms of Automated Music Generation. Wien, New York: Springer.

PAHARIA, Rajat (2013). Loyalty 3.0: Big Data and Gamification Revolutionizing Engagement. http://de.slideshare.net/gzicherm/rajat-pahariag-summit2013.

PAMLER, Doug, Steve LUNCEFORD and Aaron J. PATTON (2012). “The Engagement Economy: How Gamification is Reshaping Businesses.” Deloitte Review 11: 52–69.

RAESSENS, Joost (2006). “Playful Identities, or the Ludification of Culture.” Games and Culture 1(1): 52–57. London: SAGE Journals.

REILHAC, Michel (2010). “The Game-ification of Life.” Power tot he Pixel, October 26. http://thepixelreport.org/2010/10/26/the-game-ification-of-life/.

SCHELL, Jesse (2010). When Games Invade Real Life. Accessed March 31, 2014. http://www.ted.com/talks/jesse_schell_when_games_invade_real_life.html.

SCHMIDT, Sebastian (2005). Glaube – Herrschaft – Disziplin. Konfessionalisierung und Alltagskultur in den Ämtern Siegen und Dillenburg (1538-1683). Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh.

TERSTEEGEN, Gerhart (1729–1769). Geistliches Blumen=Gärtlein Inniger Seelen. oder, Kurtze Schluß=Reimen, Betrachtungen und Lieder, Über Allerhand Wahrheiten des Inwendigen Christentums. Frankfurt and Leipzig: G.C.B. Hoffmann.

WERBACH, Kevin and Dan HUNTER (2012). For The Win. How Game Thinking Can Revolutionize Your Business. Philadelphia: Wharton Digital Press.

WITZMANN, Reingard (2006). “’Sposi, Amici, al Ballo, al Gioco!…’ Zur Soziologie des Gesellschaftstanzes auf der Bühne und im Ballsaal.” In Mozart. Experiment Aufklärung, edited by Herbert Lachmayer, 403-414. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz.

ZEDLER, Johann Heinrich (1791). Grosses vollständiges Universallexikon Aller Wissenschaften und Künste. Halle and Leipzig: Zedlers Verlag. Digital Version available from Bayrische Staatsbibliothekat. http://www.zedler-lexikon.de/index.html?c=blaettern&bandnummer=01&seitenzahl=40&suchschluessel=ze010040

ZICHERMANN, Gabe and Christopher CUNNINGHAM (2011). Gamification by Design: Implementing Game Mechanics in Web and Mobile Apps. Sebastopol: O’Reilly.

ZICHERMANN, Gabe and Joselin LINDER (2013). The Gamification Revolution. How Leaders Leverage Game Mechanics to Crush the Competition. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional.

Ludography

Der allezeit fertige Menuetten- und Polonaisencomponist. 1757. Developed by Johann Philipp Kirnberger. musical game.

Der Frommen Lotterie. 1769. Developed by Gerhard Tersteegen. card game.

Einfall, einen doppelten Contrapunct in der Octave von sechs Tacten zu machen ohne die Regeln davon zu wissen. 1758. Developed by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. musical game.

Gioco filarmonico, o sia maniera facile per comporre un infinito numero di minuetti e trio anche senza sapere il contrapunto : da eseguirsi per due violini e basso, o per due flauti e basso. 1790 (or 1793). Probably developed by Joseph Haydn. musical game. Luigi Marescalchi.

Hasard. fourteenth century (or earlier). dice game.

L’Hombre. fourteenth century. Spain. card game.

Musikalisches Würfelspiel. 1792. Developed by Nikolaus Simrock (or arguably Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart). musical game.

Pharo. eighteenth century. card game.

SuperBetter. 2012. Jane McGonigal. https://www.superbetter.com

Author

Mathias Fuchs studied computer science in Erlangen and Vienna (Vienna University of Technology), and composition in Vienna (Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Wien) and in Stockholm (EMS, Fylkingen). He has pioneered in the field of artistic use of games and is a leading theoretician on game art and games studies. He is an artist, musician, media critic and professor at Leuphana University Lüneburg. He is also director of the Leuphana Gamification Lab.

Résumé

Cet article retrace l’historique d’un phénomène aujourd’hui appelé ludification, mais déjà vu, revu et exploité avant l’ère numérique. On lit souvent que le concept de ludification a été inventé par Pelling et rendu populaire dans les années 2010 par Deterding, Khaled, Dixon et Nake (2011), McGonigal (2011), Zichermann (2012) et al.

Le discours universitaire sur la ludification a vraiment commencé en 2006 avec Joost Raessens. Il y a pourtant des précurseurs à l’idée que notre société est habitée et infiltrée par le jeu. Dans cet article, l’auteur présente des exemples de cette ludification avant la lettre et se réfère aux idées développées depuis la 2è partie du XVIIIe siècle, entre autres par Gerhard Tersteegen, David Roentgen, CPE Bach, et Mozart.

Mot-clés : gamification, ludicisation, lotterie, Spielsaeculum, 18ème sièce

Notes

[1] A few sections (2, 3 and 4) of this article are based on a text on gamification that has been published in the volume « Rethinking Gamification“ (Fuchs et al. 2014)

[2] German original: “Gamification ist die Durchdringung unserer Gesellschaft mit Metaphern, Methoden, Werten und Attributen aus der Welt der Spiele” (Fuchs 2013).

[3] “Gamification is taking things that aren’t games and and trying to make them feel more like games“ (Schell 2010).

[4] “There is no doubt that video games are the emergent form our times and that the process of gamification is transforming our world, contaminating it like never before“ (Reilhac 2010).

[5] Translation by the author, German original: “Das gegenwärtige Jahrhundert könnte man in den Geschichtsbüchern nicht besser, als unter dem Titel: Das Freygeister=Journal und Spielsaeculum nennen”.

[6] In Spain the game was called “Juego del tresillo” and there was the Spanish set of cards used lacking the eights and nines.

[7] Translation by the author, German original: “Angenehmer Zeitvertreib lustiger Scherz-Spiele in Compagnien”. (anonymous 1757. Frankfurt and Leipzig, quoted by Bauer 2006: 383)

[8] The lottery started on 25 February 1695 and lasted for four weeks.

[9] Translation by the author, German original: “zwar ein geringes, doch trug die gute Nahrung von dem ganz ungemeinen Zulauf der Fremden, da alle Häuser bis unter die Dächer voll gestecket, ein weit größeres ein.“ Zedler, Universallexikon (1791)

[10] See Salomon Kleiners “Apartement pour les Jeu” from the first half of 18th century as found in Lachmayer 2006.

[11] Translation by the author, German original: “Er errichtete einen Berg von 3640 Brettspielen, an die 40.000 Würfel, Kartenspiele ohne Zahl und 72 Schlitten und verbrannte dieses sündhafte Luxuswerk” (Dirx 1981, 82).

[12] Translation by the author, German original: “so daß sich allerhand Gesinde bei ihm einfinde und spiele” (Schmidt 2005).

[13] I owe Sébastien Genvo and Carl Therrien thanks for having made me aware of this game with the goal of gamifying religious content.

[14] “Celuy qui arrivera au nombre 35. ou est LOUIS LE GRAND, ne payera rien, et jra au nombre 59. ou est Ierusalem par ce que c’est luy qui à beaucoup travaillé a la revision.” (D’Allemagne ca. 1690, 210)

[15] “La chaire de pestilence, ou preside l’esprit d’erreur (Psalm.1).” (D’Allemagne ca. 1690, 210)

[16] cf. Descamps Elise (2006) A Metz, le temple Neuf raconte l’histoire des huguenots. le 17/11/2006 http://www.la-croix.com/Archives/2006-11-17/A-Metz-le-temple-Neuf-raconte-l-histoire-des-huguenots.-_NP_-2006-11-17-276891

[17] Translation by the author, German original: Der Frommen Lotterie. The Pious Lottery was part of Tersteegen’s Geistliches Blumengärtlein. This book included the Pious Lottery at latest in the fourth edition, published in 1769.

[18] Translation by the author, German original: “Diß ist der Frommen Lotterie,/ wobei man kann verlieren nie,/ das Nichts darin ist all so groß,/ als wann dir fiel das beste Los”.

[19] When 18th century musicians used card games and dice to facilitate composition processes, they aimed at something that is similar to contemporary gamification attempts in the field of marketing: the former wanted to implement a layer of fun and entertainment and they wanted the audience to believe that they were composing. Actually the audience did not compose; they were just instrumental in starting algorithmic processes. The latter try to implement a layer of fun and entertainment above the functional level of marketing and they want the customers to believe that they desire what they are told to desire. In both cases rule-based ludic systems service as persuasive devices for a subject matter that is not play. That is why I speak of gamification in the context of music and in the context of recent marketing, even if the object of gamification differs in both cases.

[20] The examples for aleatoric composition methods given here do not claim to tell about the earliest attempts to do so. There is a history of aleatoric composition in the 18th century, in the digital age (Nierhaus 2009) and much earlier than that. Already in the 17th century, composers had begun thinking of a music piece as a system of units which could be manipulated according to chance processes. Around 1650, the Jesuit Athanasius Kircher invented the arca musurgica, a box filled with cards containing short phrases of music. By drawing the cards in combination, one could assemble polyphonic compositions in four parts.

[21] Translation by the author, German original: Der allezeit fertige Menuetten- und Polonaisencomponist.

[22] Translation by the author, German original: Musikalisches Würfelspiel.

[23] Translation by the author, German original: Einfall, einen doppelten Contrapunct in der Octave von sechs Tacten zu machen ohne die Regeln davon zu wissen.

[24] Translation by the author, French original: Table pour composer des minuets et des Trios à la infinie; avec deux dez à jouer.

[25] Translation by the author, Italian original: Gioco filarmonico, o sia maniera facile per comporre un infinito numero di minuetti e trio anche senza sapere il contrapunto : da eseguirsi per due violini e basso, o per due flauti e basso.

[26] English: “Beloved ones, Friends, let’s Dance, let’s Play!”.

[27] Translation by the author, German original: Spielplatz rarer Künste.

[28] The full title of Schellenberg’s book is A Glance/ at/ Döbler’s and Bosko’s/ Magical Cabinet,/ consisting of/ New Enchantment from the Field of/ Natural Magic/ that is Useful for Social Life. (Translation by the author, German original: Ein Blick/ in/ Döbler’s und Bosko’s/ Zauberkabinet,/ bestehend/ in neuen Belustigungen aus dem Gebiete/ der natürlichen Magie,/ im gesellschaftlichen Leben anwendbar, Huber 2006, 335).

[29] Johann Sebastian Halle’s book was published by Joachim Pauli in 1783 in Berlin as Magic,/ or/ Magical Power of Nature,/ Revised to Take Account of Entertainment and Serious Applications. (Translation by the author, German original: Magie,/ oder, die/ Zauberkräfte der Natur,/ so auf den Nutzen und die Belustigung/ angewandt worden,/ von/ Johann Samuel Halle,/ Professor des Königlich=Preußischen Corps des Cadets/ in Berlin, Huber 2006, 335).

[30] Translation by the author, German original “wissenschaftliche Spiele wie die Mineralogie”.

[31] Johan Wolfgang von Goethe’s autobiographical raisonnement called From my Life: Poetry and Truth (German original: Aus meinem Leben. Dichtung und Wahrheit) was written between 1808 and 1831. It is said to be a reflection on Goethe’s life in the 1750s to1770s. The phrase about „scientific games“ is quoted from Kaiser 1967.

[32] “Based on our research, we propose a definition of ‘gamification’ as the use of game design elements in non-game contexts” (Deterding et al. 2011).

[33] “Gamification is taking things that aren’t games and trying to make them feel more like games” (Schell, 2010).

[34] The Video to the rock song with the title of Californication by the Red Hot Chilli Peppers is a perfect example for gamification of pop music.