MEGHAN BLYTHE ADAMS

University of Western Ontario

Abstract

Based on close textual analysis of Tomb Raider (2013) and Rise of the Tomb Raider (2015), this article uses Georges Bataille’s work on the role of ritual sacrifice to interrogate the video game industry’s depictions of women in need of rescue. Tomb Raider (2013) and its sequel present the endangerment, rescue, and death of women as sites of pleasure for the player; additionally, the player can experience both the role of sacrificer and proxy-sacrifice through gameplay. Through an exploration of these themes, this article ultimately questions the player’s culpability with regards to the proliferation of the female sacrifice trope in games and the treatment of women in game culture.

Keywords: Tomb Raider, ritual sacrifice, damsel in distress, video games, culpability

Résumé en français à la fin du texte

Introduction

Through close textual analysis and Georges Bataille’s work on the role of identity in ritual sacrifice from The notion of expenditure (1933) and Hegel, death and sacrifice (1955), I interrogate depictions of women in need of rescue in Tomb Raider (2013) and Rise of the Tomb Raider (2015). I argue that at the narrative level, the game subverts this trope, but the consistent staging of endangerment, rescue and death as sites of pleasure for the player prevents the subversion from going any deeper than the text’s surface. Ultimately, this paper aims to raise questions of player culpability with regards to the proliferation of the female sacrifice trope in games. Rather than looking at player-character death as a game mechanic, as much of the key critical work on death in video games does (Westfahl, 1996; Aarseth, 1997; Juul 2005; Galloway, 2006; Tocci, 2008; Juul, 2013; Flynn-Jones 2015), I will consider the narrative use of female sacrifice more broadly. First, I will discuss the cultural trope of the damsel in distress, then I will look at how this trope operates in video games specifically. I want to articulate how the depiction of women in peril provides important context for the concept of player-character death as a form of ritual sacrifice: the thrill of sacrifice relies on our fascination with how the erotic and the violent intersect in the body of the female victim. I will then look at the representation of sacrifice in Tomb Raider (Crystal Dynamics, 2013) and Rise of the Tomb Raider (Crystal Dynamics, 2015) in detail before considering the role of the game industry and the game player with regards to this trope’s future in light of Gamergate.

Your Princess is in Another Castle (Still Chained Up)

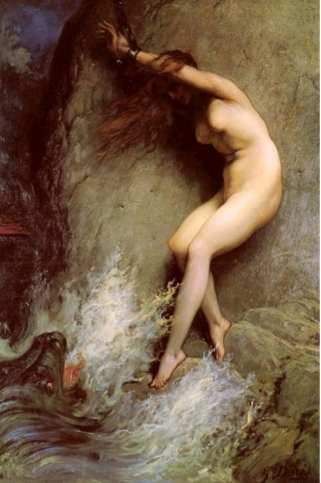

I would like to begin with the image of a character that prefigures the sacrificial female in video games: Andromeda of Greek myth, chained to the rocks and about to be sacrificed to a monster, before being rescued by hero Perseus (Figure One).

Figure 1: Gustave Doré’s Andromeda (Wikimedia Commons)

Gustave Doré’s 1869 painting depicts Andromeda as nude, helpless, and restrained by chains. From the lower left-hand corner of the image, a monster approaches. Perseus is absent and it appears that Andromeda is about to be killed. I want to draw attention to the fact that typically, in both classical and modern art, Andromeda is depicted naked (or nearly naked) and helplessly bound while awaiting rescue or death. The image of Andromeda in art is charged with a high degree of erotic potential. This erotic potential derives not only from Andromeda’s nudity and chains, but more specifically in relation to her peril and the potential staging of her ritual sacrifice to the monster. In Hegel, death and sacrifice, Georges Bataille describes “the palpable and intentional excitement of sacrifice […] The excitement of which [he] speak[s], is definable; it is sacred horror: the richest and most agonizing experience” (1955, p. 94). Part of the erotic appeal of Andromeda on the rocks is the prospect of this excitement – the possibility of her sacrifice continuing uninterrupted by the arrival of the rescuing hero. The possibility that Andromeda will be devoured, rather than rescued, is a possibility charged with both erotic and horrific appeal, agonizing because some part of the spectator’s mind anticipates the perverse pleasure of seeing her killed. Consider the appeal of spectator sports like NASCAR; the real thrill is the possibility of a fatal crash.

In video games, we see Andromeda transposed in the classic damsel in distress character. While this common set-up of a vulnerable female romantic object that must be rescued from the possession of a monster or a villain is not exclusive to games, it is a key game plot that relies heavily on the trope of the sacrificial female, who resembles the classic depictions of Andromeda.[1] Anita Sarkeesian identifies the myth of Andromeda as a forerunner of the damsel in distress in “Damsel in Distress: Part 1 – Tropes vs Women.” Like Andromeda, the sacrificial female helplessly awaits rescue by a hero who claims her as a romantic conquest in exchange for saving her. Both are often physically restrained while being menaced by a monster or villain. Some iterations of this trope are post-sacrifice: the hero must avenge the sacrificial female, who dies at the beginning or the middle of the game’s plot. The original Donkey Kong arcade game (Nintendo, 1981) features the earlier pre-sacrifice example, while WATCH_DOGS (Ubisoft, 2014) has multiple depictions of both the pre- and post-sacrifice examples. As noted by Mia Consalvo in Hot dates and fairy-tale nights: Studying sexuality in video games, the common video game trope of the damsel in need of rescue hails back to early examples such as the character first named Lady, then Pauline, in 1981’s Donkey Kong (2003, p. 172). Consider the first stage of the game: the player must control Jumpman, avoid rolling barrels, and maneuver him up the girders to rescue Pauline from the monstrous ape that has kidnapped her. We see her calling for help, which reinforces that the game is not merely about mastering the skill and timing required to jump over barrels; these are actions in the service and context of rescuing a woman from a monster. This trope has been discussed in detail in Anita Sarkeesian’s Tropes vs. Women series in a three-part series on the Damsel in Distress (2013). The sheer abundance of games utilizing this trope is staggering; Sarkeesian points to Donkey Kong as the most famous early example of its use in video games in “Damsel in Distress: Part 1 – Tropes vs Women in Video Games”. In the years since the release of Sarkeesian’s first season of Tropes vs. Women, little has changed in terms of the prevalence of the damsel in distress. There are three sacrificial females in WATCH_DOGS (Ubisoft, 2014): the protagonist Aiden loses or risks losing his niece Lena, his associate Clara, and his sister Nicole. Lena is killed early in the game by assassins attempting to kill Aiden, while Clara is killed at Lena’s gravesite. Nicole manages to survive the events of the game, though Aiden’s efforts to rescue her from a kidnapping are a significant portion of the gameplay. WATCH_DOGS’ largely non-romantic examples of sacrifice depict women over whom Aiden has a familial or social sense of responsibility, which viewed through a patriarchal lens still may entail degrees of ownership.

Across video game history, iconic series such as Super Mario and The Legend of Zelda feature kidnapped romantic interests. The rescue arc initiated by the kidnap of these romantic interests presents both the pleasure of preparing the sacrifice, and averting it. This arc offers players the opportunity (and sometimes even the necessity) of metaphorically chaining naked Andromeda to the rock, enjoying the scopophilic pleasure of observing her in her bound state, and culminates in heroically rescuing her (Mulvey 1975).[2] The endangered sacrificial female in video games titillates while presenting an opportunity for heroism. By playing the game, the player participates in the damsel’s endangerment as much as her heroic rescue and is encouraged to enjoy both actions. While instances drawn from the rebooted Tomb Raider series are my key examples in this paper, these dual pleasures can be found across game genres and periods. How a player might experience this offer likely differs from one individual to another, but the prospect is consistently presented as a site of, and opportunity for, pleasure.

A Threefold Sacrifice: Bataille, Identity and Ritual

The philosophy of Georges Bataille, particularly as expressed in his texts The notion of expenditure (1933) and Hegel, death and sacrifice (1955), provides a theoretical context for my use of the ritual sacrifice concept. In his reading of Hegel, Bataille explains the specific method through which humanity attempts to circumvent the problem of misrepresenting death, namely, the act of ritual sacrifice:

Concerning sacrifice, I can essentially say that, on the level of Hegel’s philosophy, Man has, in a sense, revealed and founded human truth by sacrificing; in sacrifice he destroyed the animal in himself, allowing himself and the animal to survive only as that noncorporeal truth which Hegel describes and which makes of man, in Heidegger’s words, a being unto death (Sein zum Tode), or, in the words of Kojève himself, “death which lives a human life”. (1955, p. 194)

In Bataille’s reading, sacrifice is a response to the necessity of dwelling with the negative, using both representative and literal means which combine sacrifice as well as play. I would like to assert here that player-character death can be considered as a kind of ritual sacrifice performed by the player in the space of the game. In ritual sacrifice, the one performing the sacrifice identifies with the sacrificial object, much like the player does with the player-character. Bataille writes, “In the sacrifice, the sacrificer identifies himself with the animal that is struck down dead. And so he dies in seeing himself die, and even, in a certain way, by his own will, one in spirit with the sacrificial weapon” (1955, p. 194-195). In sacrifice, identity becomes plural, shared among the key elements of sacrifice. The role-playing game Dragon Age: Origins (Bioware, 2009) enacts this plurality in the latter stages of the game. The player-character, a Grey Warden charged with protecting the kingdom of Ferelden against the encroaching armies of the orc-like Darkspawn, is presented with a quandary. Grey Wardens traditionally are charged with killing the dragon leading the Darkspawn armies; in doing this, the Grey Warden takes in the soul of the dragon so both of them permanently die. The player-character is expected to take part in a sacrifice like the one described by Bataille, and in so doing, simultaneously becomes both killer and killed.

This narrative plays out in the function of player-character sacrifice in general gameplay. In player-character death, play as a fusing of belief and pretense, as well as the player’s identification with the player-character, are in alignment with Bataille’s description of the sacrificer’s identification with the object of sacrifice, and with the sacrificial weapon. It even incorporates the tragicomic element that Bataille identifies in ritual sacrifice before adding: “At least it would be a comedy if some other method existed which could reveal to the living the invasion of death” (1955, p. 195). Ritual sacrifice, which is the closest the sacrificer can come to experiencing death, is both comic and tragic. This is reflected in the tone of the many video game characters’ death compilation videos available on YouTube, with titles like The many ways Mario has been killed in his twenty-five years of gaming (2012). These compilations place various levels of emphasis on tragic and comic elements, combining deaths ranging from cartoonish to gory with the comedic device of portraying many deaths in quick succession and occasional accompaniment by a soundtrack. However, tragedy persists beneath the comic elements: laughing at death does not change its fundamental power over us.

The tragi-comic ritual sacrifice of the player-character is a long-running trope in the Tomb Raider series. From the series’ first installment in 1996 to its most recent in 2015, Lara Croft’s deaths have always been tinged with degrees of humour. Her early deaths are particularly funny: her screams as she falls to her death only accent the clunky collapse of her polygonal body. Throughout most of the franchise’s existence, Lara’s deaths have been comic rather than grisly, but the 2013 reboot of the series sharply changes the tone of Lara’s death scenes.

Spectacle and Death Animations

Since 2013, Lara’s deaths have been undeniably spectacular; they are crisply animated and the accompanying audio presents the sounds of injuries as they are inflicted, her cries of panic and pain, and her final gasps before dying. We can see minute movements as Lara fruitlessly tries to grasp at objects impaling her (as in Figure Two, where she has a pipe impaling her from the base of her head, well into her skull). The technical details of these deaths are matched by dramatic staging: Lara is impaled on branches and pipes, mauled by wolves, and strangled.

Figure 2: « Tomb Raider Definitive Edition Death Scenes Montage » (Youtube)

The changing ratio of comedy to drama and evolutions in technology have made Lara’s new death scenes some of the most eye-catching content ever produced by the franchise (this appeal can be seen in the view counts of Youtube compilations like Tomb Raider Definitive Edition Death Montage (2014), which has a relatively unimpressive roughly 257 000 views at the time of this writing, in contrast to the over 6 200 000 views of Tomb Raider All Death Scenes / Violent Deaths Compilation 18+ (2013) (Figure Two). Lara’s death scenes (be they funny, horrifying or both) have a great deal of precedent in games. Bataille writes in Hegel, death and sacrifice that “the spectacle of sacrifice makes his humanity manifest” (1955, p. 199). What distinguishes this spectacle for Bataille is the scale and force of the display: it overpowers us with gaiety and anguish. Historically, media has reacted to, and condemned, the violent spectacles presented in video games, particularly as a kind of overpowering visual seduction. Concern over the colourful flashing screen in the dark arcade has undertones of paranoia surrounding the power of spectacle. Violent spectacle in video games has also been the object of multiple moral panics, with concerns ranging from the violent driving in the arcade game Death Race (Exidy, 1976) to the match-ending fatalities of the Mortal Kombat series. However, it is the increasingly overt eroticism of Lara’s death throes that particularly connote Bataille; key feminist critiques of Bataille have frequently debated whether his depiction of erotic violence against women undercuts his usefulness to feminist thought (Dworkin, 1989) or in fact substantiates it (Sontag, 1967; Schultz, 1987). Here his unabashed celebration of the beautiful, brutalized female is useful specifically because it is an example of that eroticism at work. I say this not to undercut or devalue feminist critique of Bataille, but to draw parallels between this eroticism at work in philosophy, as it is in Bataille, and in video games, as it is in Tomb Raider (Crystal Dynamics, 2013), and more broadly.

Player-character death animations frequently invoke this power of violent spectacle. From the early days of commercial video games, player-character death has generally had two key distinguishing features: a special combination of animation and audio that signifies death, and a slowing and/or suspension of gameplay. Observing the death of Mario in the classic platform game Super Mario Bros. (Nintendo, 1985), we can identify a special animation sequence in which Mario’s body is thrown upwards before falling off the screen, accompanied by a musical cue still associated with Mario’s death in modern iterations of the franchise, followed by a Game Over screen and a minor key version of the Super Mario Bros. theme. Versions of this format in which the dead or dying player-character is shown to quickly rise and fall (the latter motion often taking them off-screen) have persisted in death animations for platform games ever since. Player-character death as a form of ritual sacrifice frequently contains within it an element of spectacle: from Mario falling off the screen to the gory demise of Lara Croft, the death of the player-character is both an interruption of play and an audiovisual display that characterizes the presentation of death in the game. Underneath these variations in tone, the scene of player-character death remains an eruption of spectacle in the course of game-play.

Digging Up Tomb Raider: Putting the Series in Context

The particular game text that most clearly demonstrates this dual pleasure of specifically enacting female peril and rescue is the franchise reboot Tomb Raider (Crystal Dynamics, 2013). Since her first appearance in the original Tomb Raider (Core Design, 1996), Lara Croft has remained the subject of intense critical analysis because she is a gun-toting female protagonist, but one whose breasts are as famous as her twin pistols. Academic engagement with Lara’s potential feminist and anti-feminist implications (and analysis of the nature of that academic engagement) can be traced back to early references in Cassell and Jenkins’ From Barbie to Mortal Kombat; as noted by MacCallum-Stewart, references by authors of essays in their collection, including Jones, Subrahmnyam and Greenfield, and Cassell and Jenkins themselves, are often negative and identify Lara as innately anti-feminist even when quotations from interviewees and research subjects speak positively of her (MacCallum-Stewart, 2014, Cassell and Jenkins, 1998). MacCallum also notes two key pieces of criticism which have further explored Lara’s complexities, beyond her portrayal as a flatly misogynist character; Helen W. Kennedy’s Lara Croft: Feminist icon or cyberbimbo? On the limits of textual analysis (2002) and Diane Carr’s Playing with Lara (2002). MacCallum-Smith’s article Take that, bitches!: Refiguring Lara Croft in feminist game narratives (2014) examines the sex-negative, fan-discounting tone of much Tomb Raider criticism within game studies. These four points of reference – Cassell and Jenkins, Kennedy, Carr and MacCallum – show the progression of academic discussion on Lara. Popular cultural discussions of the character have shown less evolution, as noted in the descriptively-titled Two Decades of Breathtakingly Sexist Writing About Tomb Raider by Joseph Bernstein (2013). Bernstein’s article is tongue-in-cheek but it illustrates that even the most well-meaning attempt to discuss Lara risks retreading sexism both overt and subtle. What this signifies is that Lara remains an immensely fraught character, subject to a great deal of hotly debated gendered analysis that must be acknowledged prior to any further discussion.

Burnt Offerings: Tomb Raider (2013)

While the 2013 release of Tomb Raider ostensibly departs from the long-running trope of the sacrificial female, its use of female characters put in peril and rescued as a source of pleasure undercuts this innovation. In the reboot, Lara is a young archeologist at the beginning of her career. Lara’s youth and inexperience are emphasized through references to her age in dialogues, her fearful reactions to danger early in the game, and her increasingly exposed and injured body. She is trapped on the island of Yamatai after her research expedition is shipwrecked. The island is populated by a group of exclusively male cultists, the Solarii Brotherhood, who have littered the island with dead bodies, killing or converting men who come to the island and ritually sacrificing any women they come across. In this section, I will first look at the game’s narrative engagement with female sacrifice through two key characters – Lara’s friend Sam, and a priestess named Hoshi whose story is told in documents found by Lara. Then, I will look at the game’s thematic engagement with the sacrificial female in the animations in which Lara’s peril ends in death rather than survival.

In the script of Tomb Raider, the spirit of the ancient Sun Queen Himiko, ruler of Yamatai, is transferred from body to body through ritual female sacrifice. However, the interruption of this ritual many years prior to the events of the game trapped the Sun Queen’s spirit in the corpse of the most recent sacrifice. Since then, the Sun Queen’s spirit has caused storms around the island of Yamatai, trapping survivors, who eventually form the cult that kidnaps Lara’s friend Sam. The bulk of the game’s narrative is taken up by Lara’s efforts to find Sam and the other survivors from her ship’s crew, and rescue Sam before the cult sacrifices her to become the Sun Queen’s new host. In contrast to Sam, Hoshi is a long-dead princess who committed suicide after realizing she was intended to be a host for Himiko. The game ostensibly deviates from the standard trope of the sacrificial female in video games: the cult who kills women is the enemy, and Lara brutally kills its members throughout the game. Lara, our female lead, is the hero, not the damsel. But by looking more closely at the game, we can see the cracks in its apparent subversion of the trope. While Sam and Hoshi are candidates for sacrifice to the Sun Queen, Lara’s sacrificial role is more thematic. I will discuss each in turn and how they retread or insufficiently resist the damsel in distress trope that the game ostensibly rejects.

In Sam’s case, she rather neatly fits the role of damsel in distress. As a descendant of the Sun Queen, she is sought by the cult as an ideal candidate to become Himiko’s new host. She is kidnapped three separate times in the game and Lara’s mission is explicitly to save her from the cult. In a nod to the classic trope of the kidnapped romantic object, the nature of Lara and Sam’s relationship has some romantic overtones. In short, Sam is not particularly different in this regard from early incarnations of Princess Peach. She is a female romantic object the hero player-character must repeatedly save from peril. The game features a scene in which Sam argues with one of her captors that she doesn’t want to be sacrificed. He responds, “This is not about what you want. It’s about what you are” (Crystal Dynamics, 2013). He refers here to her bloodline, but his pronouncement also references her gender, her lack of agency as a character, her lack of opportunities to make choices, and her continuation of the tradition of the sacrificial female in media and video games, whose rescue is as much a ritual as her peril. “You saved me, I knew you would” says a white-robed and flower-crowned Sam to Lara at the close of the game, before Lara bridal-carries Sam to the boat on which they and a few other survivors will escape the island (Crystal Dynamics, 2013). The fact of the matter is that we all knew she would. This rescue arc is a ritual too. In a 2013 KillScreen interview Rhianna Pratchett says that because of the heterosexism typical of the damsel in distress trope, “It was interesting that with a female [protagonist] like Lara rescuing a female, people sort of projected that there was more going on to that relationship” (Tomb Raider Writer Rhianna Pratchett on why every kill can’t be the first and why she hoped to make Lara Croft gay, 2013). Consider this statement in light of Wittig’s deconstruction of oppressive heterosexuality (1981), mentioned by Trépanier-Jobin and Bonenfant (2017) in this issue of Kinephanos: the romantic heterosexual pull of the damsel in distress trope is so powerful that many fans reacted to the game by assuming Lara is in love with Sam. On one level, this reading is a challenge to the heterosexual rescue arc: the possibility of both rescuer and rescued being queer women seems like a powerful subversion of the trope. This reading also potentially integrates (we might say, domesticates) a threat to heteronormativity in the form of a strong, non-romantic female friendship, by pulling it back into the heteronormative framework that does not openly acknowledge queer identity or desire. I hesitate to fully endorse either position, but I think the combination of the game’s narrative and thematic emphasis on women in peril undercuts the game’s positive potential.

In contrast to Sam, the character Hoshi, whose story is told through ancient documents discovered by Lara, presents an alternative model for action as opposed to the inaction available to the sacrificial female. Realizing she is being groomed to be the Sun Queen’s next host body, Hoshi commits suicide during the ritual. She traps the Sun Queen’s spirit in her dying body, and Himiko spends centuries in Hoshi’s corpse, using her power to trap shipwrecked survivors on the island, building her cult, and trying to find another viable candidate for possession. Faced with her role as a female object of sacrifice in a cycle that shows no end in sight, Hoshi uses self-harm as a form of resistance, but one that we need to critique. In another document, one of the Sun Queen’s military officers writes, “The princess [Hoshi] knew only death could save her” (Crystal Dynamics, 2013). This begs the question as to whether self-harm is the only expression of agency offered to female characters other than the hero(ine), Lara? What are the implications of positioning self-harm as resistance when it is the only form of resistance available? I hesitate to provide an easy answer, but I question whether the use or enduring of violence as a character’s primary or only path to agency is an improvement on the trope of the sacrificial damsel; it may be a lateral move at best.

Gameplay: Lara on the Rocks (Mauled by a Wolf and Impaled on a Branch…)

Lara differs from Sam, Hoshi, and the many female corpses found burned in shrines around the island in the sense that she is never a candidate for sacrifice to the Sun Queen; her sacrificial role, however, is an offering to the very trope Lara is supposed to resist. The gruesome death animations common to the Tomb Raider series (particularly this edition) offer a higher-intensity version of the sacrificial female erotically chained to a rock and left for the monster. The game’s death scenes use the quick-time event as a moment of peril, heightened by the tension surrounding attempts to avoid death by pressing the correct buttons, or killing Lara on purpose with the desire of watching various possible deaths. The scenes depict our digital Andromeda not just chained up, but vividly killed in a spectacle offered up to the player.

I would suggest that the player is both observer and participant in these scenes, not just controlling and identifying with Lara, but also participating in her death even when it is unintentional. As previously discussed, Bataille sees the identity of the sacrificer, sacrificed and the sacrificial weapon as intertwined (1955, p. 195). In this edition of Tomb Raider, the player is not only given the opportunity to enact Lara’s exciting endangerment and potentially heroic survival or grisly death; the player also identifies with Lara in this process. Relating to Lara as avatar while holding the game controller, the player may also become the sacrificer through letting her be crushed by a boulder, experiencing the sacred horror and potential pleasure of either her peril and survival, or her peril and death, as both murderer and victim. I say this not to claim that all players will approach Lara’s deaths the same way, but that the text offers up this experience to each player.

Play it Again, Lara: Rise of the Tomb Raider (2015)

Rise of the Tomb Raider presents a post-traumatic Lara Croft; her experiences in the previous game have shaped her into a competent adventurer and killer, but one who is prey to the psychological fallout of the events on Yamatai. This Lara is a less obvious sacrificial female at the level of plot, and the game’s fewer thematic connections to female sacrifice reflect this change. However, Lara’s death scenes remain both detailed and invasive, showing that her added experience and capability do not exempt her from being offered up to the player to kill or save. The game’s reduced thematic resonance with the idea of the sacrificial female is evident from its plot and primary characters. Lara’s mission is to locate an artifact that her father failed to find, rather than to avert the newest sacrifice in a long series; from this we can infer that this second game is concerned with inheritance, rather than sacrifice. At the level of character, the more hardened Lara is hurt by the absence of the oft-rescued Sam. In the interquel comics, Sam is portrayed as remaining partially possessed by Sun Queen Himiko, and is housed in a mental institution; the cover of the eighteenth issue depicts the scene where Sam refuses to continue seeing Lara (Pratchett, 2015, p. 19). Sam’s absence and the reason behind it indicate that the final sacrifice of Sam was not successfully averted in the reboot; Lara failed to save her friend, even though Sam’s rescue is what fed the scant positivity of Tomb Raider’s ending. In the Tomb Raider franchise, subsequent media has rendered the rebooted series’ most easily identifiable sacrificial female absent. The sequel, however, continues the reboot’s treatment of Lara’s deaths, which are violent and varied; over the course of the game she can be impaled on spikes, mauled by a bear, stabbed in the throat and drowned, among several other potential ends (Crystal Dynamics, 2015). As in the previous game, the death scenes are often prolonged as Lara’s dying spasms taper off and cease. The scenes’ intense technical detail and content are very similar across the two games. The greatest contrast between the first and second games’ death scenes is that the sequel features fewer incidences of Lara being impaled (particularly through the throat); the sequel also features fewer death scenes that linger on Lara’s anguished facial expressions as she dies. These changes seem to place less emphasis on the sexual connotations of the penetration of Lara’s body. One potential interpretation is the intention to show a less stark image of Lara’s death, though the difference between the two games is small. Despite Lara’s character evolution, her deaths remain the same.

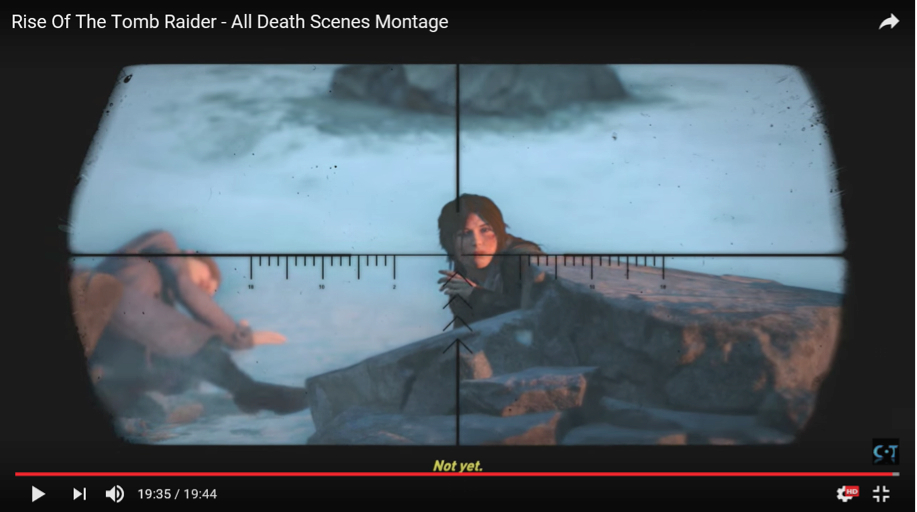

Ultimately, both Tomb Raider (Crystal Dynamics, 2013) and Rise of the Tomb Raider (Crystal Dynamics, 2015) present Lara as a figure imbued with vulnerability, positioned to be saved or sacrificed by the player. Rise of the Tomb Raider’s post-credits scene encapsulates the promise held out to the player: Lara interrogates Ana, the woman who appears to have betrayed Lara’s father; during the interview, a sniper kills Ana, robbing Lara of the answers Ana could have provided. The shot cuts to the sniper’s perspective as he reports the kill and asks what should be done with “Croft”. A mysterious voice instructs the sniper not to shoot, saying “No. Not yet” as the scope’s cross-hairs remain aimed at Lara’s face (Figure Three).

Figure 3: « Rise of the Tomb Raider – All Death Scenes Montage » (Youtube)

This typical post-credits scene, meant to present a hook for an upcoming sequel, presents Lara in danger, with her death only deferred – not prevented. The player is invited to solve the mystery of Lara’s father’s death and either save her from, or condemn her to, a shadowy threat that literally has her in its sights (the sniper’s scope circles her face in the final shot). Once again, it is the player’s intervention or inaction which will decide her fate. This final image of Lara presents her as endangered and at the mercy of the player, while simultaneously offering a means by which the player can experience the horror of being a sacrificial object; Lara’s final twitches and cries can become ours, at least temporarily. Even after the events of the two games, she remains a sacrificial offering to the player’s whims and vicarious thrills. We can contrast Lara’s erotic spasms with the heroic stoicism of grizzled helmsman Grim, capable mentor Roth, and computer geek Alex, all of whom sacrifice themselves to save Lara at different points in the first game. Their deaths are choices made to protect Lara; admirable, rather than erotic or inviting. Their death scenes are characterized by camera cuts to Lara’s anguished reactions, rather than a sustained focus on their dying moments.

Once More, With Bears: Repetition and Sacrifice

The ubiquity of Lara’s deaths, starting out with blocky polygonal collapses in Tomb Raider (1996) and evolving into slickly detailed cinematics of her death throes in 2013 and 2015, recalls the repetition of ritual sacrifice in games. The game Journey (thatgamecompany, 2012) seems to confront the criticism that repetition in games renders them meaningless. The game consists of a seemingly Sisyphean set-up and imbues that repetition with meaning. The hooded player-character begins its journey in a desert and proceeds toward the far-off light of a mountain. During the course of the game, the player-character endures difficulty and eventually dies partly up the side of the lit mountain. After dying, the hooded figure appears to be reborn and reaches the light at the summit; as it walks into the light, a shooting star falls back to the desert where the game began, and the player is invited to restart. In a game with virtually no written or spoken words beyond the invitation to play, the idea that the game must repeat is very clear. Instead of making the repetition into drudgery, the game reinforces the meaning of that repetition, highlighting the worth of the journey itself over the attainment of a goal. Journey specifically demonstrates how the repetition in games can be part of their strength. In the game Bioshock Infinite (Irrational Games, 2013), after dying, a new Booker appears to be another called forth from a fractal expanse of universes. The mechanism through which the player-character’s death is circumvented is not so much the classic instantaneous respawning, but the replacement of one iteration of the player-character with another. His daughter Elizabeth literally pulls a new Booker out of a ‘tear’ in the fabric of reality. Booker is repeatedly revived specifically because he must die at the climax of the story. He is a much-replaced player-character, saved only because he eventually has to die at the right time, in the right way. Multiple alternate-universe versions of Elizabeth hold him under water at the site of the religious conversion that turns some versions of Booker into the game’s villain Zachary Hale Comstock. Booker’s deaths model play as a temporary deferral of death, repeated as needed until death is no longer meant to be avoided.

In contrast to Journey (thatgamecompany, 2012) and Bioshock Infinite (Irrational Games, 2013), Tomb Raider (Crystal Dynamics, 2013) and Rise of the Tomb Raider (Crystal Dynamics, 2015) do not incorporate the player-character’s death and resurrection into the plot; Lara’s death scenes are vivid but exist outside the narrative of the game. Instead Lara’s deaths preface the opportunity to reload a save, effectively undoing the detailed death throes the player has so recently seen. The potent combination of the death animation’s technical detail and prurient content is immediately effaced once players regain the ability to input commands into the game through the controller, making Lara’s deaths more cinematic than ludic. To play Lara in her current incarnation is to constantly stave off bursts of her mortality. The fates of the robed figure, Booker, and Lara seem to literalize “The idea of death in the philosophy of Hegel,” which asserts that Man “differs from Nothingness only for a certain time” (Kojève, 1947, p. 71). Particularly in the case of Booker and Lara, their existence in between their deaths is a temporary lull rather than a life. But where Journey (thatgamecompany, 2012) and Bioshock Infinite (Irrational Games, 2013) invoke criticisms of repetitive player-character death and show how the repetition of player-character death can actually heighten that death’s significance, Tomb Raider (Crystal Dynamics, 2013) and Rise of the Tomb Raider (Crystal Dynamics, 2015) place the worth of Lara’s death spectacle outside the field of play as the player becomes both cause and victim of Lara’s vivid death. As in the case of fan interpretations of Lara and Sam’s relationship, I hesitate to describe this as revolutionary. However, the question arises: is the opportunity to become Lara in death a potentially feminist act, or does it merely recycle the scopophilic pleasure of watching her die? I argue that to some extent, it does both.

Pleasure and Horror in Video Games, Or, The Grisly Fate of Pac-Man

Whatever the worth ascribed to sacrifice by games that contain it, the ritualized killing of an individual is a key aspect of player-character death, fusing the exciting risk of the self and the horrific death of the other. Bataille writes:

The excitement of which I speak, is definable; it is sacred horror: the richest and most agonizing experience, which does not limit itself to dismemberment but which, contrary, opens itself, like a theatre curtain, onto a realm beyond this world, where the rising light of day transfigures all things and destroys their limited meaning. (1955, p. 194)

In Bataille’s estimation, the act of sacrifice transfigures the scope of our experience to include a glimpse of the unknowable; namely, death. The sacrifice of the player-character by the player is similarly perspective-altering because it allows the player to enact her own death by proxy in the player-character. It is only half-jokingly that I bring up the eponymous hero of Pac-Man as a figure of sacrifice (Midway, 1980). Upon death, Pac-Man’s mouth traditionally opens so wide that the black space of his mouth engulfs the yellow space of his being. Looking at this representation closely, it is a horrific figure; in a game about the act of eating, Pac-Man’s final act is to eat himself, performing the kind of auto-cannibalism that Bataille might discuss with glee. Reading the death animation with this level of seriousness may sound ridiculous, but the fact that Pac-Man’s self-swallowing is at first glance so banal, yet upon consideration, so horrifying, was one of the earliest inspirations for this article’s close look at player-character death as an act of sacrifice performed by the player through the player-character, representing a sacrifice of the self. Pac-Man’s death and Lara’s death are not so different; both contain pleasure and horror that the player can observe and experience firsthand.

Every player-character death resembles ritual sacrifice to the extent that it contains some combination of pleasure and horror. The ratio of these elements to one another characterizes the particular player-character death, from the cyclic, ritualized deaths of Journey to the excruciating spectacle of Tomb Raider. Bataille writes that “…sacrifice, like tragedy, was an element of a celebration; it bespoke a blind, pernicious joy and all the danger of that joy, and yet this is precisely the principle of human joy; it wears out and threatens with death all who get caught up in its movement” (1955, p. 198). In the ritual sacrifice of the player-character, the player is threatened with being caught up in the dangerous joy of the ritual, imagining her own death as she sacrifices her in-game double. The sacrifice of the player-character is often rather closer to the surface than it may (or may not) be in Pac-Man (Midway, 1980). As I have previously claimed, the deaths of Lara Croft in the 2013 version of Tomb Raider (and to a lesser extent, in its 2015 sequel) explicitly and implicitly address the theme of sacrifice, specifically ritual female sacrifice. Recurring references to sacrifice, particularly of women, recurs in the work of Bataille; he portrays a female victim in the hands of a male sacrificer that could easily stand in for Lara Croft in her role as victim and proxy sacrifice to a presumed male player in the detailed death scenes of the two most recent Tomb Raider games. Furthermore, that the image of a woman in danger and pain functions as a common erotic spectacle unavoidably calls to mind the ongoing public harassment of women in gamer culture, including but certainly not limited to Leigh Alexander, Anita Sarkeesian, and Zoe Quinn by the online hate movement known as Gamergate (Cross, 2014).

Questioning Player Culpability

This leads me to the question of player culpability in the sacred horror of female sacrifice, both in Tomb Raider’s player-character deaths and in the broader trope of women in peril. In The notion of expenditure, Bataille writes that “…sacrifice is nothing other than the production of sacred things” (1933, p. 120). The ubiquitous trope of the imperiled sacrificial female is both a cliché and a sacred cow of video game culture and history. Its stature is reinforced not only every time Peach is kidnapped by Bowser, but every time Lara’s struggles eventually diminish after being impaled on a pipe. I should note here that the prospect of the sacrifice of a non-player-character (as in the case of Peach or Sam) entails a less degree of player identification than the player-character herself being killed by a non-player-character, another player-controlled character or even an environmental hazard (as in Lara’s impalements). What unites them is the shared visual spectacle of a woman in pain and peril, even as their degree of player identification differs. Across platforms and genres, these female characters are not just sacrificed to Bowser or the Sun Queen, but to the player’s pleasure and the popularity of the trope itself. The many tropes that feature women under threat in less obvious ways are similarly self-perpetuating and damaging, no matter how noble and beautiful the woman is said to be. Wittig writes of the category woman that “In order to be aware of being a class and to become a class we first have to kill the myth of ‘woman’ including its most seductive aspects. (I think about Virginia Woolf when she said the first task of a woman writer is to kill ‘the angel in the house’)” (1981: 106). Ironically, the many deaths of the damsel and her ilk have only further sustained the trope under which they operate; killing the princess (or angel) has only strengthened the myth. What, therefore, is the responsibility of the player with regards to the proliferation of the trope? Is the responsibility of the player not to play, and in so doing, avoid reiterating the predicament of the sacrificial female? How might player responsibility extend to the harassment of women by the Gamergate movement and its insistence on terrorizing real, living women and non-binary people, offering them up as unwilling sacrifices to toxic masculinity in game culture? I am unsure as to how player culpability must ultimately be negotiated in regards to these issues, but I believe that we, as players, must acknowledge the scopophilic pleasures offered to us by games, admit to what degree we enjoy the thrill of sacrifice of our virtual and real Andromedas (whatever our political and moral alignments), and finally recognize how game culture tacitly facilitates the spillover of these into everyday life through failing to adequately disavow harassment campaigns like Gamergate.

Conclusion

The game industry’s reliance on the female sacrifice’s presumed appeal should be critiqued and resisted. Tomb Raider (2013) appears to do just that, but the game’s use of Sam, Hoshi and Lara as sacrificial victims undercuts its subversive potential. Its sequel, Rise of the Tomb Raider (2015), lacks the overt trope of female sacrifice, but retains the same type of death cinematics and emphasis on Lara’s vulnerability as its predecessor. This continuation suggests that the mainstream game industry may not be able to resist relying on the potential pleasures of enacting the damsel’s peril and rescue/death. As a result, the game industry may continue to eroticize the figure of the woman in peril even in ostensibly feminist games.

If players continue to be offered pleasure via observation, enactment, and (through the proxy of female player-characters like Lara) identification with sacrifice, the next step in this research is to look more deeply at player participation in this trope at narrative, ludic and cultural levels. How do players of various identities respond to being offered these pleasures, and how can players resist or critique these tropes? These are the questions we must ask, even/especially if mainstream game developers cannot, or will not.

Bibliography

ADAMS M. B. (2015), “Renegade sex: Compulsory sexuality and charmed circles in

Mass Effect”, Loading…: The journal of the Canadian game studies association, vol. 9, 14 (Autumn), p.40-54.

BATAILLE G. (1985), “The notion of expenditure [1933]”, trans. by A. Stoekl, C. R. Lovitt, and D. M. Leslie, Jr., in A. Stoekl (ed.), Visions of excess: Selected writings, 1927-1939, Minneapolis, MN, University of Minnesota Press, p. 116-129.

BATAILLE G. (2004), “Hegel, death and sacrifice [1955]”, in D. King Keenan (ed.), Hegel and contemporary continental philosophy, New York, SUNY Press, p. 187-204.

CARR D. (2002), “Playing with Lara”, in G. King and T. Krzywinska (eds.), ScreenPlay: cinemas/videogames/interfaces, London: Wallflower Press, p. 171-180.

CASSELL J. and H. JENKINS (eds.) (1998), From Barbie to Mortal Kombat: Gender and computer games, Cambridge, MA, The MIT Press.

CONSALVO M. (2003), “Hot dates and fairy-tale romances: Studying sexuality in video games”, in M. J.P. Wolf and B. Perron (eds.), The video game theory reader, New York, Routledge, p. 171-194.

CROSS K. (2014), “We Will Force Gaming to be Free: On Gamergate and the Licence to Inflict Suffering”, First Person Scholar, <http://www.firstpersonscholar.com/we-will-force-gaming-to-be-free/>.

DORÉ G. (1869), Andromeda, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Paul_Gustave_Dore_Andromeda.jpg>.

DWORKIN A. (1989), Pornography: Men Possessing Women, New York, Penguin.

FLYNN-JONES E. (2015), “Don’t Forget to Die: A Software Update is Available for the Death Drive”, in T.E. Mortenson and J. Linderoth (eds.), Dark Play: Difficult Content in Play Environments, Florence, KY, Routledge, p. 50-66.

GALLOWAY A. (2006), Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture, Minneapolis, MN, University of Minnesota Press.

JUUL J. (2005), Half-Real: Video Games Between Real Rules and Fictional Worlds, Cambridge, MA, The MIT Press.

JUUL J. (2013), The Art of Failure: An Essay on the Pain of Playing Games, Cambridge, MA, The MIT Press.

KENNEDY H. W. (2002), “Lara Croft: Feminist icon or cyberbimbo? On the limits of textual analysis”, Game studies: The international journal of computer game research, vol. 2, no. 2 (December).

KOJÈVE A. (2004), “The idea of death in the philosophy of Hegel [1947]”, in King Keenan (ed.), Hegel and the Contemporary Continental Philosophy, New York, NY, State of University of New York Press, p. 27-74.

LEJACQ Y. (2013), “Tomb Raider writer Rhianna Pratchett on why every kill can’t be the first and why she hoped to make Lara Croft gay”, Kill Screen, <https://killscreen.com/articles/tomb-raider-writer-rhianna-pratchett-why-every-kill-cant-be-first-and-why-she-wanted-make-lara-croft-gay/>.

MACCALLUM-SMITH E. (2014), “Take that, bitches!: Refiguring Lara Croft in feminist game narratives”, Game studies: The international journal of computer game research, vol. 14, 2, (December). <http://gamestudies.org/1402/articles/maccallumstewart>.

MULVEY L. (1975), “Visual pleasure and narrative cinema”, Screen, vol.16, no. 4 (Autumn), p. 803-816.

PRATCHETT R. (2015), Tomb Raider #18: Cold Light of Day, Milwaukie, OR, Dark Horse Comics.

SARKEESIAN A. (2013), “Damsel in Distress: Part 1 – Tropes vs. women in video games” <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X6p5AZp7r_Q>.

SCHULTZ K.L. (1987), “Bataille’s L’Erotisme in Light of Recent Love Poetry”, Pacific Coast Philology, vol. 22, no 1/2, p. 78-87.

SHERMAN S. R. (1997), “Perils of the princess: Gender and genre in video games”, Western Folklore, vol. 56, no 3/4 (Summer), p. 243-258.

SONTAG S. (1967), “The Pornographic Imagination”, The Partisan Review, (Spring), p. 181-212.

TOCCI J. (2008), “You are Dead. Continue?: Conflicts and Complements in Game Rules and Fiction”, Eludamos: Journal for Computer Game Culture, vol. 2, no. 2, p. 187-201.

TRÉPANIER-JOBIN G. and M. BONENFANT (2017), « Bridging Boundaries Between Game Studies and Feminist theories », Kinephanos, Special Issue: Gender Issues in Video Games (July).

UNKNOWN AUTHOR (2012), The many ways Mario has been killed in his twenty-five years of gaming (Original), <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WLx1Ozrtad8>.

UNKNOWN AUTHOR (2013), Tomb Raider All Death Scenes / Violent Deaths Compilation 18+, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9qfDiULrnjI>.

UNKNOWN AUTHOR (2014), Tomb Raider Definitive Edition Death Montage, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WeG9MuzUppM>.

UNKNOWN AUTHOR (2015), Rise of the Tomb Raider – All Death Scenes Montage, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q2VkxygqZ4o>.

VANDERVEES C. (2014), “Complicating Eroticism and the Male Gaze: Feminism and

Georges Bataille’s Story of the Eye”, Studies in 20th and 21st Century Literature, vol. 38, no 1.

WESTFAHL G. (1996), “Zen and the Art of Mario Maintenance: Cycles of Death and Rebirth in Video Games and Children’s Subliterature”, in G. Slusser, G. Westfahl and E.S. Rabkin (eds.), Immortal Engines: Life Extension and Immortality in Science Fiction in Science Fiction and Fantasy, Athens, Georgia, University of Georgia Press, p. 211-220.

WITTIG M. (1981), “One is not born a woman”, Questions Féministes (Nouvelles Questions Féministes & Questions Feministes), vol. 8, p. 75-84.

Games Cited

Bioshock Infinite. Irrational Games. 2013. PC game.

Death Race. Exidy. 1976. Arcade game.

Donkey Kong. Nintendo. 1981. Arcade game.

Dragon Age: Origins. Bioware. 2009. Xbox 360 game.

Journey. Thatgamecompany. 2012. PS3 game.

Legend of Zelda. Nintendo EAD. 1985. NES game.

Mortal Kombat. Midway Games. 1992. Arcade game.

Pac-Man. Namco. 1980. Arcade game.

Tomb Raider. Core Design. 1996. PlayStation game.

Tomb Raider. Crystal Dynamics. 2013. PS3 game.

Rise of the Tomb Raider. Crystal Dynamics. 2015. Xbox One game.

Super Mario Bros. 1985. Nintendo R&D4. NES game.

WATCH_DOGS. Ubisoft. 2014. PS3 game.

Meghan Blythe Adams is a PhD candidate at the University of Western Ontario. Their research interests include death and difficulty in games, as well as depictions of genderqueerness and non-normative sexuality in media more broadly. They can be contacted at madams42@uwo.ca or @mblytheadeams.

Résumé

Cet article s’articule autour d’analyses textuelles détaillées des jeux Tomb Raider (2013) et Rise of the Tomb Raider (2015), à la lumière des textes de Georges Bataille portant sur le rôle du sacrifice rituel, afin de mieux comprendre les représentations de la demoiselle en détresse véhiculées dans l’industrie du jeu vidéo. Le jeu Tomb Raider (2013) et sa suite présentent la mise en danger, le secours et la mort des femmes comme une source de plaisir pour le joueur. De plus, le joueur peut à la fois expérimenter le rôle de sacrificateur et celui de sacrifié. Ultimement, cet article cherche à interroger la culpabilité du joueur par rapport à la prolifération du stéréotype de la femme sacrifiée dans les jeux vidéo.

Mots-clés : Tomb Raider, sacrifice rituel, demoiselle en détresse, jeux vidéo, culpabilité

Notes

[1] Further analysis on the heterosexual rescue arc has been done in Sherman’s Perils of the princess: Gender and genre in video games (1997), Consalvo’s Hot dates and fairy tale romances: Studying sexuality in video games (2003), and Adams’ Renegade sex: Compulsory sexuality and charmed circles in Mass Effect (2015).

[2] The use of Mulvey to positively connect Bataille’s theories of eroticism to feminist critique can be found in Chris Vanderwees’ Complicating Eroticism and the Male Gaze: Feminism and Georges Bataille’s Story of the Eye (2014).