Volume 7, Issue 1, November 2017

LEANDRO AUGUSTO BORGES LIMA

King’s College London

Abstract

The gendered marketing of videogames is an underexplored topic within the vast literature of games and gender. In this paper, I contribute to this body of literature a configurative analysis on gendered marketing strategies for the Mass Effect. I explore the genealogy of the configuration concept and propose an expansion of it based on communication theory. Subsequently, I analyse the configurative dynamics between marketing, company, and gamers that resulted in a shift from male to female focus in Mass Effect’s marketing materials in the course of 10 years since the first game’s release.

Keywords: Configuration, Mass effect, Marketing, Gender, Communication theory

Introduction

Originally, videogames were marketed as family entertainment aimed for everyone, and usually took place at arcades or at home (Kocurek, 2015; Lien, 2013). However, the videogames industry has been historically described as male-oriented and directed toward a technomasculine audience: an idealized male gamer who is technologically-savy, militaristic, and competitive (Kocurek, 2015, p.10). From an economic perspective, marketing to everyone was the right decision at first; videogames were still new and niche, and to succeed, the industry needed as many gamers as possible. But this has changed over the years; several researchers argue that the crash during the eighties was a turning point for the industry, where practitioners in every sector had to rethink their strategies (Kline et al, 2003; Kerr, 2006; Wolf, 2008). To rise again, companies realised their marketing should be targeted more precisely, given that the financial risk forced companies to evolve with a specific public in mind. According to Ian Bogost, in an interview for Tracey Lien (2013), Nintendo was the main company responsible for this marketing shift as it chose to focus on a young male demographic, a claim also made within historical videogames research (Kline et al, 2003, p.109-127; Wolf, 2008; Ryan, 2011).

Although videogame scholars often contend with matters of gender representation within games (Shaw, 2014; Leonard, 2006; Cassell & Jenkins, 1998), less work has been done regarding this political matter within videogames marketing material. Burgess et al’s (2007) study on videogame covers regarding presence/absence and portrayal of female characters, Ivory (2006) and Fisher’s (2015) studies on matters of representation within videogames review are three of the few examples of academic research in this field. This paper intends to fill this gap by considering gendered videogames marketing as part of a configurative circuit that affects companies’ marketing strategies and their relationships with the gamer community.

The first part of this paper argues that ‘configuration’ is a key concept to understanding videogames in three spheres: the medium-sphere relating to the materiality of videogames, the console, the software, the controller, and the contractual aspects of this “mediatic device” (Antunes and Vaz, 2006); the moment-sphere which is the playing of the game and what surrounds and informs the game itself; and the culture-sphere which encompasses the different aspects of everyday life that configure videogame play: politics, marketing, industry choices and cultural backgrounds, among others. The second part presents a case study of the Mass Effect franchise’s marketing strategies and the configurative dynamics put into play during a gender-oriented shift in those strategies. Although the game presents a customisable, non-canon[1] main character, who can be either male or female, the marketing for the two first games only portrayed a male version of the protagonist, Commander Shepard. In the campaign for the third game, Bioware incorporated the female character – Female Shepard or FemShep as referred to by Mass Effect’s community of players – within their marketing. However, the manner of this inclusion is also problematic according to the franchise players and fans, as the female character is perceived as very generic in terms of design. The shift to female-focused marketing persists in the campaign for the fourth game, Mass Effect: Andromeda. This case study relies on data collected from various sources, including interviews with Mass Effect players, official marketing material, and online conversations from Twitter, Reddit and BSN (Bioware Social Network – Unofficial). The data was organized and thematically coded using NVivo, and then analysed under the configurative framework presented further.

The exploration proposed here has two objectives: firstly, to uncover the configurative dynamics that occur when a company’s marketing discourse is contested by a share of its target audience, taking into account a gendered history of marketing and videogames. Due to the considerable penetration of Mass Effect as a mainstream game, understanding the marketing strategies adopted by Bioware and the reverberation of those strategies within its consumer base sheds light on industry practices, both in terms of repetition of strategies and its innovative, closer relationship with gamers. Secondly, the analysis seeks to present and test a theoretical framework – namely, a configurative circuit framework – to analyse videogames and the diverse elements that constitute this industry. The research fits within a broader spectrum of games and gender research, contributing to the critical analysis of the industry regarding its male-centric approach, focusing on the role of marketing in reinforcing hegemonic discourses to secure sales, and how these configurative dynamics affect videogames production and consumption.

1. Configurative Circuit: a praxeologic perspective of configuration

As a means of communication, videogames present certain intrinsic characteristics that tell of possible interactions and modes of meaning production that distinguish them from other media. In the search for a terminology that reflects what is unique in videogames, a useful theoretical contribution is the concept of configuration proposed by Steve Woolgar (1991). Within game and videogame studies, the concept was appropriated by other authors (Eskelinen 2004, Moulthrop 2004, Dovey and Kennedy 2006, Harvey 2015) and evolved from describing a close human-machine relationship, to one that explains the relationship between game and player which accounts for the network of social, cultural and political relations that configure gaming.

Woolgar’s work, an ethnographic study of the launch of a new computer, focuses on the usability testing of the product and how the perception of these differs in each sector of the company. He notes that alongside the understanding of the machine comes an understanding of its potential users (Woolgar, 1991, p. 61). The hypothesis is that the machine configures certain parameters that the user needs to adjust. In setting up the machine, the user must find the perfect way for the machine to work, taking into account the needs of not just one, but a myriad of possible users – one of the company’s biggest challenges (Woolgar, 1991, p. 68-69). Woolgar considers that this relationship is not unidirectional, since the machine also takes into account the capacity of the user (Woolgar, 1991, p. 68), but does not evolve to what we might call a dialogical perspective. There is therefore, according to Woolgar, a limit to the configurative dynamics between user and machine.

The subsequent use of Woolgar’s concept by Eskelinen & Tronstad (2003) considers the importance of the action and structure of the game system – typical elements to a ludological perspective – as vital components of a configurative performance in which “the game structure cues, guides, and constrains the player’s activities (or gameplay)” (Eskelinen and Tronstad, 2003, p. 208). Moulthrop (2004) points out that the concept must also be concerned with systems other than computational systems, and that subjects should have “active awareness of systems and their structures of control” (Moulthrop, 2004, p.57). Such systems would be, for example, social and political structures that may also confine the gaming experience. In this sense, heteronormativity, patriarchalism, and sexism are systems that configure certain aspects of the social for certain subjects, and as presented in this paper, can manifest themselves via the marketing discourse of a company and/or an individual game. Configuration, then, ceases to be a concept focused on technical aspects of human-computer interaction and begins to establish a dialogue with the social. This evolution also affects the analysis of play and game itself, reinforcing the dialogic aspects as part of a “feedback loop circuit” where the “player and the game” are “agents in the processes of gameplay” (Dovey & Kennedy, 2006, p. 105). In this sense, there is a network of relationships that circumscribes videogames as practice and complicates interactions that inform gaming practices.

I argue, therefore, that configuration cannot be limited to the moment of play, but is a communicational phenomenon that also occurs before and after playing. The interface between videogames, configuration, and communication proposed here takes place under a praxiological perspective of communication (Quéré, 1995) that builds on the work of pragmatists and symbolic interactionists alike (Mead, 1934; Dewey, 2005, 2012; Goffman, 1959, 1962), as applied to the study of everyday practices of communication and sociability in the context of media by França (2006, 2008). A praxeological perspective considers communication as a complex set of influences and experiences of everyday life, where we, as subjects in and of communication, are constantly mutually affected by the other, the media, the environment, the city, and a wide network of relations (França, 2006). These experiences shape how we interact with the world and interpret it (França & Quéré, 2003). The concept of configuration, therefore, refers to those meanings shared through experience and action, in which subjects are not only in interaction but « in discursively mediated interactions » (France, 2006, p. 77) with the other, with language, and with the symbolic.

Comprehending videogames (and videogame marketing) from a praxeological perspective understands it as a configurative medium inscribed into society as a cultural object and communication practice, configured of and by symbolic gestures and mutual affectation, and capable of affecting gamers and creating unique experiences influenced by past and future experiences. The subjects involved in such relationships are subjects in communication, organized in a network of relations that constitute “not (the) subject on singular, but on plural; and not only subjects in interaction, but in discursively mediated interactions” (França 2006, p. 77). It is through configuration that the videogaming public – the gamer – emerges as a subject in communication.

Configuration is therefore a unique mode of interaction and experience within videogames. Understanding videogames as a configurative media encompasses human-machine interaction, narrative and contractual (rule-based) aspects of gaming (Juul, 2005; Murray, 1999), and the broad network of relationships that informs videogames as a medium, a cultural token and practice of sociability.

1.1. Configurative Circuit: a framework of analysis

This paper contends that videogame studies can benefit from a triadic perspective of this configurative medium. Three spheres operate in this regard, separately and simultaneously: the medium-sphere, moment-sphere and culture-sphere. The medium-sphere relates to the videogame as a mediatic device, which is the specific materiality of texts and discourses, a process of meaning production, a means for interaction order and a process through which significant meanings are transmitted (Antunes e Vaz, 2006, p.47). Videogames’ medium-sphere is primarily concerned with hardware and software’s affordances (Gibson, 1979) of videogames, such as its ludic form, narrative capacity, the programmed code and its limitations.

The moment-sphere is what occurs during a gameplay session: the body connected to the machine, the feedback loop of actions and responses, and the haptic communication with the hardware. The moment-sphere also encompasses the experiences of the gamer before play, and the social discourses – the network of relations – configuring what Goffman calls the “gaming encounter”: an “organic system of interaction” (Goffman, 1961, p.33) where each decision made is informed by several external factors.

Finally, the culture-sphere expands the role the network of relations plays within videogames practice. It analyses videogames as part of the social tissue, an important element of digital culture, and their relationship to established discourses, products, and the organization of everyday life. It encompasses, among other issues, social discourse on gender and sexuality; everyday politics on a macro and micro level; the capitalist system and neoliberal ideology; the circuit of production, consumption and prosumption (Jenkins, 2006); and the marketing discourse of a console or game. All these aspects act as configurative elements of videogames practice and culture.

There are several high-quality studies published addressing each of these spheres individually, or with similar approaches, e.g. Taylor’s proposal of an assemblage of play (2009). This study instead proposes naming the framework as a configurative circuit, pointing to the need to adopt a more dynamic approach and focusing on videogames from a communicative perspective. Given that these three spheres operate simultaneously, analysis can be devoted to one of these spheres in isolation, which considers the mutual configuration with the others, but does not deepen its lone aspects. It can also search for the intersection of two or more spheres. For example, how choice of hardware may result on a particular type of game session. However, a cross-sectional analysis is ideal. The layering of the spheres creates complexity: at each moment, one or another element will have more prominence in the analysis of the phenomenon, but always being configured by and configurative of other aspects. It is crucial that analysis tries to capture as much of this configuration-reconfiguration dynamism as possible.

Configuration is a continuous action; videogames configure (subjects, industry, culture, society etc.) and are configured by (subjects, industry, culture, society etc.). Previous configurative models within games studies are restricted in their scope by their exclusive focus on self-sufficient ‘spheres’. This paper responds to those limitations by attempting to observe with a microscope one aspect of the cultural sphere (marketing) without isolating it completely; rather, the marketing discourse surrounding the Mass Effect franchise is connected to broader systems of belief, dominant discourses, personal experiences, market needs, capitalism, and the gendered history of videogames.

2. The Male Dominance in the Marketing Discourse

Maclaran’s (2012, 2015) feminist take on the relationship between marketing and gender is a good starting point for discussion. Based on a thorough review of marketing studies, she draws a parallel between the different waves of feminism and various readings of marketing made by feminists during each period. As claimed by Maclaran, marketing was an ally of the first and third waves of feminism. In the former, she argues that the suffragette movement benefited from a certain kind of high-class marketing discourse that transformed department stores into safe spaces for women to gather and discuss their actions (Maclaran, 2012 p. 463). However, this apparently beneficial relationship was not perfect, as it also sparked the first ideas surrounding ideals of femininity, dictating certain norms of conduct and beauty (Maclaran, 2012 p. 464). These issues were challenged by second wave feminism that considered “market as a patriarchal system that was all about manipulation and ideological control” (Maclaran, 2012 p. 465). Indeed, as Goffman’s (1979) analysis of advertising images indicate, women had a very particular role in marketing, either as a lascivious figure to attract the consumer, or as a reinforcing image and stereotype of femininity. Videogames marketing tends to fall within the same tropes, and as Kocurek (2015) argues, they contribute to the establishment of a gamer culture of “technomasculinity” that strongly defines videogames culture – albeit partially.

During the third wave, feminism was called upon to take a more intersectional perspective, taking into account other systems of oppression, multiple feminisms, and feminist voices beyond those of white middle-class women (Maclaran, 2015, p. 1733). The concept of gender was also thoroughly questioned by Butler’s (1990) ground-breaking work. Yet, stereotypically gendered marketing has been apparently substituted by identity-oriented marketing. Consumerism reconciles with feminism because purchase power, financial independence, and freedom to choose one’s own identity through consumption, becomes a form of empowerment (Maclaran, 2012 p. 466). Certainly, said changes do not come without criticism, but Maclaran considers that most of the academic critique was “subsumed into broader gender research” rather than handling the specifics of marketing and gender (Maclaran, 2015 p. 1734).

Curiously, Maclaran’s approach speaks directly to Richard’s (2013) account of the history of videogames and gender research, where three waves are identified. The first searches for differences in the experience of gameplay according to gender (Richard, 2013, p. 270); the second builds on the former to include the dynamics of broader social and cultural contexts, including industry discourses conveyed through marketing practices; and lastly the third wave is related to intersectionality and questioning of current takes on masculinity in games research. Despite certain temporal differences, these similarities can be explored, especially in the current wave of videogames and gender research that might be moving into a fourth wave, accompanying the “fourth wave” of feminism raised by Maclaran’s study (2015). This fourth wave is highly technological, using social media to campaign around women’s rights, blending “the micropolitics that characterised much of the third wave with an agenda that seeks change in political, social, and economic structures much like the second wave” (Maclaran, 2015 p. 1734). Maclaran argues that understanding this wave is fundamental for current marketing practices that must cater to this shift. Indeed, as this paper intends to demonstrate, videogames marketing is one of the areas that deals with this shift directly, as a highly gendered industry.

2.1. Videogames gendered marketing

Marketing strategies within the videogames industry are of utmost importance as evidenced by Kline, Dyer-Witherford and Peuter’s (2003) proposal of three circuits of interactivity. The fact that marketing deserves a circuit of its own in their model is strong evidence of the role it plays in shaping this industry. The authors argue that marketing is vital to videogames producers “for selling their own cultural and technological products, and for the revenue streams from advertising other products” (2003, p. 51). Marketing strategies may also set up a so-called base audience for videogames (Kerr, 2006, p. 98-101; Kline, Dyer-Witherford and Peuter, 2003), following thorough market research on their audience, as Nintendo did after the industry crash in the eighties, which re-branded videogames as a “boy toy”.

At that moment, women were partially erased: the marketing discourse no longer had them as a target, especially in the first wave of a campaign (Kerr, 2006, p.100). Female in-game representations turn into male-gaze appreciation designs, with lascivious bodies and little to no importance in-game, aside from tropes such as the damsel-in-distress. Initiatives such as “pink games” and the Purple Moon studio by Brenda Laurel in the nineties proved there was a female public interested in gaming, and focused their research and production to develop videogames thought to be exclusively tailored for girls (Kerr, 2006, p. 98; Lien, 2014). However, in the long run they failed to establish a niche market within the industry. Thornham (2008, p. 132) argues that the perception of videogame practice as a “boy thing” potentially affects women’s adherence to gaming. There appears to be a divide that puts men inside gaming culture while excluding women from this medium, which is partially configured by marketing discourse.

Furthermore, the establishment of a visual language oriented towards a specific demographic limits the consumer base. If in its early age videogames advertisement had a broader public in mind, using less gendered images, and focusing on fun and enjoyment rather than the content itself, then industry practice could have reconfigured these discourses. Visual language, especially focused on a young male audience, is often marked by military themes and sexualized female bodies on the marketing material of videogames, as evidenced by Burgess et al (2007). The same trope repeats itself in the analysis of videogames reviews, using images that appeal to the male gaze or to an ideal of masculinity (Ivory, 2006; Fisher, 2015). These findings are in tandem with Kocurek’s proposal of technomasculinity as a powerful identity discourse within videogames culture, one that is “allied with an idealized vision of youth, masculinity, violence and digital technology” (Kocurek, 2015, p. 21)

Therefore, it is no surprise that Mass Effect’s marketing for the first and second game in the series focused on the male protagonist, despite the game mechanics allowing for the creation of a female protagonist with a voice of her own, dubbed by Jennifer Hale. Bioware’s marketing strategy for a brand-new videogame universe, initially wanted to conquer space within the main gamer public of male players. The following case study demonstrates the configurative dynamics between constructed discourses of technomasculinity within videogames culture, gendered marketing pratices, and the sci-fi universe of Mass Effect.

3. A case study of the Mass Effect franchise

3.1. The universe of Mass Effect

The Mass Effect franchise, produced by Canadian company Bioware, released its first game in 2007, and its following sequels in 2009 and 2012. The original trilogy has as its main character Commander Shepard, a fully customizable avatar that can be either male or female, homosexual, heterosexual, or bisexual, conforming to the videogame’s configurative code. Gamers, however, went beyond the limitations of said configurative code and interpreted the game’s interpersonal relationships differently as gamers can “renegotiate, appropriate, bracket and reproduce those texts and marketing for their own purposes” (Kerr, 2006, p.8). The story follows Commander Shepard on a clash against an extra-terrestrial synthetic species, the Reapers, which threaten life throughout the universe. The story is set in a distant future where Earth has colonies scattered throughout the Milky Way and humans have established diplomatic relationships with other species. The protagonist’s mission is to gather troops from different species and unite them under the ideal of saving the universe. The protagonist faces social dilemmas (e.g. decisions to exterminate or save an entire species), political controversies (decisions can have implications for diplomatic relations between species), and personal quandaries (e.g. sub-plots of xenophobia among certain species hamper relations within the team).

In 2017, Bioware released a fourth game within the franchise, Mass Effect: Andromeda (ME:A) set in a distant future after the original trilogy. The game follows either Sara or Scott Ryder’s story as Pathfinders, responsible for colonizing new worlds for the Milky Way species that traversed from it to the Andromeda galaxy. The game has similar mechanics to the original trilogy, with choice and romance being important aspects of gameplay. This analysis presents shifts in the marketing campaign from the original trilogy to the release of ME:A.

The analysis presents two separate moments within the culture-sphere of configuration. Additionally, each of those moments relate to one or both other spheres, highlighting the dynamic nature of the conceptual-analytical framework. The first part analyses male dominance in Mass Effect’s marketing in relation to wider discourses categorising videogames as a “boy thing” (Thornham, 2008) and its gendered marketing history. The marketing materials for Mass Effect both reaffirm and challenge male dominance throughout the franchise’s evolution. The second part of the analysis looks at changes within Bioware’s marketing discourse regarding the female lead for Mass Effect 3 and Mass Effect Andromeda, and the role gamers played in this change.

3.2. Methods

For this analysis, the data collected varies in format, from text and image, to video and audio sources, all of which come from the official media, official marketing campaigns, and the players’ voices. Articles discussing Bioware’s marketing for Mass Effect were collected from gaming-related news websites, such as Rock,Paper, Shotgun, Kotaku and Polygon. Official marketing materials comprised of dedicated websites,[2] with high quality images of the game cover, wallpapers, and in-game footage both in image and video formats. For ME:A, the official YouTube channel provides the main locus of the overall discussions about the game’s marketing strategies.[3]

Regarding the players’ voices, a range of comments made on Reddit, Twitter, and the unofficial Bioware forum (BSN) were manually collected. On Reddit and BSN, a random sample of discussions on threads containing the keywords “marketing”, “advertisement”, “FemShep”, “Female Shepard” and “Ryder” were collected. The Twitter data gathered tweets with the hashtag #FemShep, alongside the keyword “marketing”, and the hashtag #FemShepFriday, to track an event/celebration on February 10th 2012 that was part of Bioware’s marketing strategy for the third game release. Over 2,300 tweets were collected, with the older tweets containing the #FemShepFriday hashtag dating back to August 5th 2011, suggesting the community created it before the company used it as part of its strategy.[4]

Finally, the data includes in-depth interviews with Mass Effect players, focusing on the original trilogy, as part of a larger research project I undertook discussing the role of videogames as a political medium (Lima, 2017a; Lima, 2017b). The interviewees were selected via an online questionnaire (N= 225) sent to mailing lists, posted on the Mass Effect Reddit forum and spread via Twitter and Facebook by several participants. From the initial sample, 15 were selected that fit our basic criteria of having played the three games extensively. The selection aimed for a diverse set of interviewees regarding gender, ethnicity and sexuality.[5] All the interviewees are identified here using pseudonyms.

3.3. Analysing a questionable marketing strategy: does it contest or reinforce a technomasculine public?

The first paragraph of Commander Shepard’s description, alongside the official Male Shepard avatar, ignores the possibility of playing as a Female Shepard, yet details many other potentially customisable elements:

Mass Effect allows you to create your own customizable version of Commander Shepard (or jump in and use the pre-created character) and plunge yourself into the centre of an epic science fiction story. Choose your squad-mates, your weapons, skills and abilities, and customize your vehicles, armour and appearance – you are in complete control over your experience.[6]

For a game – and a company – which relies on character customisation, emotional engagement, storytelling, and its innovative romance mechanic that presents same-sex relationships (Heineman, 2015; Adams, 2015; Condis, 2014), the erasure of a possible female protagonist from its campaign seems awkward. Much more so considering prior information released by the company that Commander Shepard’s avatar was originally female (Sarkar, 2015).

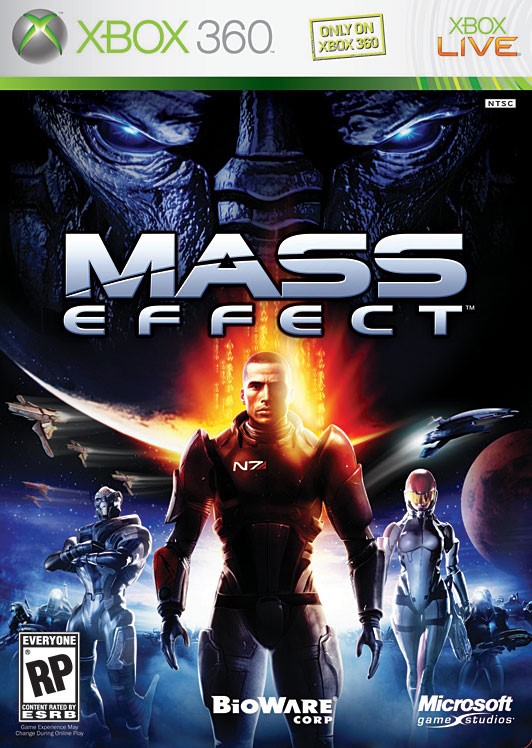

Figure 1: Mass Effect Xbox Cover

Mass Effect’s covers for Xbox 360 and PC place Male Shepard in the centre, followed by the alien teammate, Garrus, on his right side and female human teammate, Ashley, on the left side, with her face covered by a helmet but wearing a suit that closely contours her body shape (Fig. 1). This alignment of characters reflects Burgess et al’s (2007) findings on the portrayal of women on videogame covers, shown as secondary and sexualized characters, never in the spotlight when sharing cover space with male characters. Similar uses of female bodies are seen on the advertisements analysed by Goffman (1987), often showing subordinate roles through positioning in the frame, or with the prominence of certain positions and gestures of subordination (Goffman, 1987, p. 40-56). In the case of Mass Effect’s cover, the relative size of the female character indicates her lesser role in comparison to the first. Moreover, the sole exposure of a button nose and lips, and a curvilinear body is strikingly different from the main male and alien male characters that share the cover. The concealment of her eyes gives a vacant and passive impression which dehumanises the female character on first glance. This erasure of the female face and highlighting of stereotypically effeminate body features is a recurring issue in videogames adverts and a historical issue in marketing in general, such as in beer commercials (Iijima Hall and Crum, 1994). The same issue appears on the wallpapers available to download, none of which have a Female Shepard available. Other male characters have their own wallpapers, including less relevant male side characters, but only two female team members feature on their own wallpapers: human female, Ashley, and alien female, Tali.

The Gallery page has in-game screenshots, videos, and the first trailers of Mass Effect released at E3 (2007), a highly popular and influential videogames industry event. The game launch trailer and every other video available, features the standard Male Shepard avatar. The only videos that seem to portray FemShep are gameplay videos, where we see the character from the back, fully covered in armour. For seasoned players, it is possible to differentiate FemShep’s avatar from the Male Shepard, however this would be more difficult for those without previous knowledge of the game. It is worth noting that in none of the official marketing material available for analysis in their website is it possible to find an image of FemShep, nor an official statement about gender customisation.

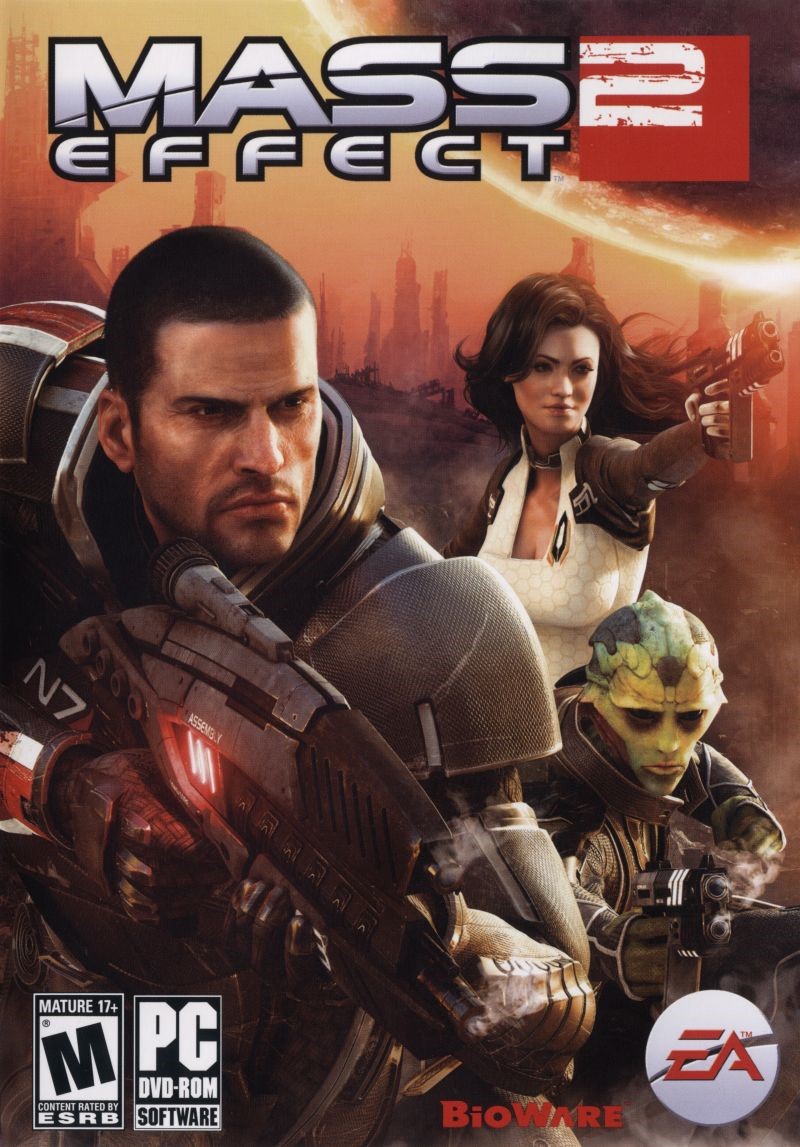

Figure 2: Mass Effect 2 cover

Mass Effect 2’s marketing repeats the same pattern of rendering FemShep invisible, albeit this time, including a female character as “eye candy” on the game cover and in other materials. Ashley, who may or may not appear during the second game, is substituted by Miranda Lawson, a controversial character due to her hypersexualisation. The facelesness of the female character disappears, and she is portrayed without a helmet and holding a gun, not as a defenseless character (Fig. 2.). She does however remain in the back of the picture, a subordinate position according to Goffman (1987). Moreover, this character portrayal in-game is met with controversy by fans, as she is developed as a genetically perfect woman and, as interviewee Rahna explains, “is there just to be hot”, which further explains her presence on the cover of the game as “eye candy” that appeals to the traditional technomasculine public.

A Female Shepard, however, remains absent. It is possible that most players of Mass Effect 2 were players of the first game, and therefore knew a female protagonist was possible even though the marketing continued to ignore it. However, as Kerr argues, marketing campaigns and the images that circulate in these “meta-texts” of a videogame “play an important role in situating the game for the fan and non-fan alike” (Kerr, 2006, p. 148). If Bioware sets Male Shepard as the canon protagonist, the Female Shepard loses its importance, and the company puts forward a certain discourse in detriment of another.

There is, however, an imbalance between the company discourse and the gamer discourse in this regard. Similar to Woolgar’s argument that the machine he marketed to his colleagues was different than the “company machine” (Woolgar, 1991, p. 78), so the videogame marketed by Bioware differs from the game played by gamers. There are several “games”, configured differently according to a set of factors external to the game itself. The “company game” is one: the fully-fledged game developed with all its mechanics, including gender customisation. The “marketing game” is another: configured by broader industry discourse that pleases the imagined technomasculine public they must sell to and by heteronormative discourses of (hyper)masculinity ingrained in society.

Historically, this male-oriented marketing discourse can be “traced back to the origin of games in male-dominated laboratories” (Kerr, 2006, p.100). The disproportionate presence of men within development studios has produced a vocal and powerful male workforce within the industry. Several researchers indicate that the gendered ICT (Information and Communication Technology) scenario influences what happens within videogames, with some arguing that a more diverse composition of work-teams could promote diversity in content and attract a more heterogeneous public to gaming (Williams et al, 2009; Shaw, 2009; Johnson, 2013). Yet, a team’s diversity in gender, ethnical, or sexual composition alone is not sufficient enough to indicate a shift in the broader industry, and dominant discourses of masculinity nonetheless carry weight in the configurative dynamics of marketing materials.

The “marketing game” of Mass Effect tries to configure the kind of experience possible to a gamer, circumscribing it to the Male Shepard and focusing on usual tropes of masculine militarisation, by highlighting the use of guns and armour in a violent, action-packed scenario. Dynamics of configuration are, however, more complex and the “player game” is more plural than the “company game” imagines it to be. Although Bioware had not initially addressed this issue, some of my female interviewees considered the possibility of a female character a “must-have” in their gameplay, and only started playing Mass Effect because of this mechanic that they discovered through interactions with other gamers or online reviews. The online comments collected reinforce the same pattern, with female gamers reaffirming the importance of a female lead, and male users acknowledging the gender imbalance in the industry. Both opinions hint towards the importance of the female character to the base of players engaged enough with it to actively participate in online communities, even so far as to discuss the game over numerous years.

Furthermore, this mechanic allows gamers to access a larger spectrum of performances and gameplay with regards to both gender and sexuality: Ron, a gay male interviewee, highlighted that it feels “right” for him to play a lesbian FemShep as they share a similar identity regarding sexuality. For different reasons, Chester, a heterosexual male, found the possibility of playing as a female lesbian character interesting, not only because of the sex scenes depicted in the game but as a chance to experiment with otherness. He also played as a heterosexual male Shepard that engaged in a relationship with every female character, an experience he describes as “completely unethical, totally ‘I am the leader of this mission, let me hook up with all the girls’”, an approach that he is aware speaks to the strong masculinity discourses embedded within videogames culture.

If marketing strategies ought to ideally reach a wider public, Bioware’s strategy, especially from the first and second games, is outdated and does not speak directly with the preoccupations of fourth wave feminists, and current society-wide debates on gender and sexuality. As Maclaran proposes, marketers should now avoid the usual “middle-class heterosexual men and women” target of their marketing research, and focus instead on exploring “intersectionality in relation to multiple femininities and masculinities” (Maclaran, 2015 p. 1735).

For example, a transgender male interviewee told the story of his “genderless”, Commander Shepard, a head-canon[7] he created in order to blur the quasi-mandatory gender roles and sexual relations offered to the player by adding “something of my own world, where I am interpreting [or configuring] the game”. He complains about the invisibility of transgender people in Mass Effect and the forceful sexual intercourse to consume a romance; an issue raised by several other interviewees who identified with a variety of sexualities, including asexuality. His play is, to an extent, a political act opposing the configurative limitations that the machine and the company try to impose, based on conventions of gender as a social construct and the insistence on biological sex as romantic male/female interaction.

There are several experiences of gameplay configured by players, despite the efforts of a marketing strategy to not disclose these possibilities to the technomasculine public, in order to secure sales within that demographic. In this way, the human goes beyond the configuration the machine tries to impose on it. The culture-sphere of configuration acts as a network of relations that are involved in constant mutual affectations, simultaneously interfering with the moment-sphere by disrupting the expectations posed by the marketing campaign and the medium-sphere, by bending the code and rules of gameplay when creating and performing an “agender” character not predicted by the machine and its creators.

3.4. Configurative dynamics between gamers and Bioware: the cases of FemShep and Sara Ryder

There is an aspect of configuration within the culture-sphere that is inherently complex. Culture is a concept difficult to grasp and define; it speaks to the social embedded in society, and in our practices. It deals, among other matters, with the diversity of cultures, societies, genders and sexualities – a diversity often too large and complex for videogames development companies to acknowledge or to demonstrate the intricacies of during game development. For instance, a videogame like Mass Effect can be highly praised for its diverse set of characters – despite it not being part of the marketing discourse – while at the same time challenged by the lack of diversity in other aspects. As one interviewee, Angelina, stated, “Bioware works with a very utopian world. Gender issues are not addressed, sexuality is not addressed, these issues seem to not exist”, referring to the in-game erasure of social prejudice that minorities deal with in real life. She complains that despite not critically addressing these issues, the game still portrays strippers and sex workers solely as females, reflecting to an extent a problematic real-life situation.

Leaving the in-world game’s political matters aside, this analysis highlights one aspect of this complex cultural dynamic of configuration between the gamer and the developing company – the change in Mass Effect’s marketing strategies once the trilogy established itself as successful. It is only in the third game that Bioware listened to some of the community’s complaints on gender and sexuality in the game and acted on it: the lack of male same-sex romance and the absence of a canon Female Shepard being the main culprits.

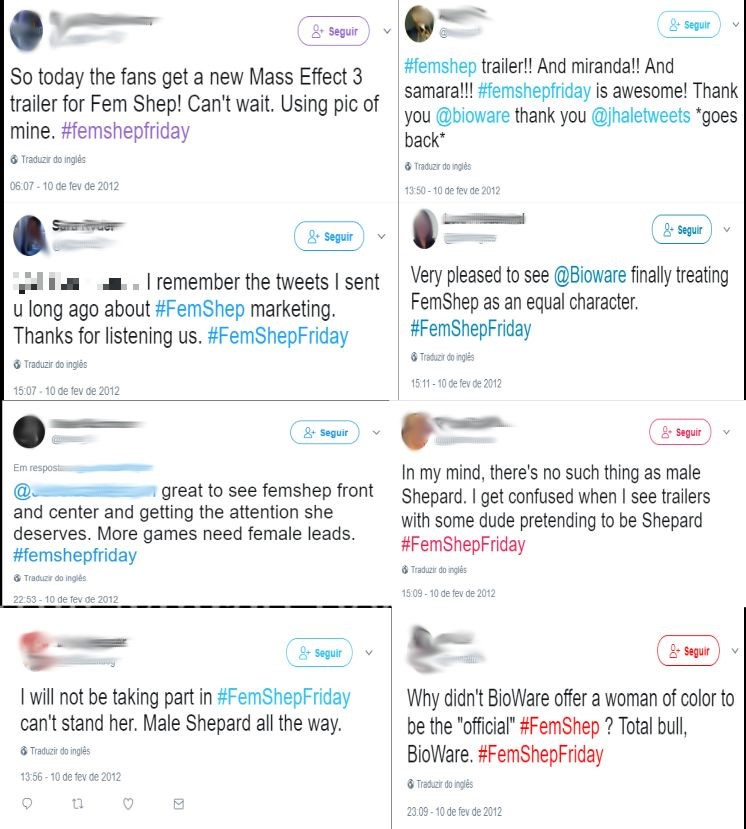

Figure 3: Twitter users demanding FemShep presence in marketing materials for ME3.

Regarding the presence of FemShep in the marketing campaign, several interviews and news sources indicate that such a decision came from community pressure on Twitter and other online spaces (Fig. 3). In an interview for videogames portal VG24/7, Bioware’s marketing representative, David Silverman, affirmed that he was “taken aback” by the vocal manifestations of passion towards the FemShep (Hillier, 2011). Despite the numbers showing huge preference for Male Shepard (Bioware’s official statistics is that only 18% of players opted for a Female Shepard on Mass Effect 3)[8] the highly engaged community of Mass Effect fans used the, at the time of writing, defunct Bioware forum and Twitter to manifest their voice. Although small in comparison to the overall buyers of the game, these die-hard fans are capable of affecting decision-making on a company level. Bioware’s marketing department opted to listen to these fans, who are often under-represented in the industry (women and LGBTQA+ players), and implemented changes in the third instalment of Mass Effect. On February 10th 2012, Bioware released a trailer for the third game using FemShep’s official design for the first time. The marketing action was accompanied by a hashtag on Twitter, #femshepfriday, that gathered more than 2000 tweets of support and acknowledgement of having their voices heard, with very few demonstrating a degree of dissatisfaction with the campaign (Fig. 4). This action represents one of marketing’s definitions, that of “communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large” (American Marketing Association, 2013), and offering successful solutions in response to their complaints. These tweets, regardless of content, were valuable consumer feedback for Bioware, resulting in their taking a carefully orchestrated marketing action, which can, ideally, be re-evaluated for future company activities.

Figure 4: Twitter user responses to the inclusion of FemShep in marketing materials for ME3

On the other hand, this shift cannot be approached uncritically. According to my interviewees, they often pointed out that videogame companies behave as if they are entitled to a ‘cookie’[9] for their good deeds regarding representation. Yet, Bioware’s strategy must be understood under a capitalist logic of production and consumption, where reaching new consumers is needed to survive. Condis (2014) points to this in her discussion on Bioware’s choice to keep same-sex romance in their games despite the ire of the traditional, technomasculine public:

BioWare ended up deciding that the business they could gain from explicitly reaching out to and including game elements requested by queer players and their allies would outweigh the business they stood to lose from straight male fans who were upset at losing their privileged status as the sole demographic game developers tried to please. This scenario complicates the usual positions of corporations and users in accounts of convergence cultures, where users are assumed to be a homogenous group pushing for more inclusive, more democratic, more open media environments and corporations are assumed to be reluctantly capitulating to the virtuous demands of the enlightened masses (Condis, 2014, p.3)

Adrienne Shaw (2014) argues that minorities are only included when “they are marketable … profitable audiences”, and when their representation in cultural products such as videogames can benefit the market logic by bringing in new consumers (Shaw, 2014, p 17-18). In this way, we see that Bioware could be criticised or praised for listening to their community, and that same community could be criticised or praised for challenging the time it takes for effective changes to happen within videogames. When changes do happen, they are not always as expected, or for the reasons assumed, as the case of Female Shepard design demonstrates.

The choice of FemShep’s official design happened through what some fans considered a “beauty contest”, where the marketing discourse helped propagate tropes of femininity – reinforcing a kind of marketing research that Maclaran condemns, one focused on typical representations of men and women (Maclaran, 2015). Bioware opened a contest for gamers to choose FemShep’s face. Six options were given with some having only a few differing features – eye or hair colour for instance – but two were in the spotlight during the contest. One was a woman of colour which ranked second in the contest. Bioware’s move to give the power of choice to the community was a double-edged sword; it reinforced open dialogue with gamers, but also enacted what Shaw (2014) considers the transference of burdens typical to neoliberalism where “subjects are responsible for them and, thus, are responsible for their own media representation” (Shaw, 2014, p. 35). In fact, the second ranked character was representative of this reluctance to diversify the lead character not only in terms of gender but also ethnicity, which is why the loss to a typical blonde character became a controversial issue.

Kirk Hamilton (2011) from Kotaku wrote a story on the case, gathering several points of view; some criticised the beauty pageant feeling to the contest, while others suggested the choice for a blonde reinforces the male audience’s preference regarding women. The final choice, however, was made by Bioware, who opted to keep the blonde winner’s facial characteristics and switch the hair colour to the red, as used in standard FemShep designs from previous games. Regardless, it is a controversial marketing decision; indeed, the fan community clamoured for a canonical Female Shepard and this is significantly important in an industry that produces noticeably few powerful female leads. However, the decision can also be merely “reduced to aesthetic pluralism” (Shaw 2014, p.36) with false power attributed to community choice as Male Shepard still dominates most of the marketing content.

A more significant shift happened with the marketing for Mass Effect: Andromeda. One of the first promotional videos released in 2015 had Jennifer Hale, the voice of Female Shepard, leaving a message to future generations, thereby assuming the role of Commander Shepard. Launched again as a prime marketing action on the well-established N7 Day,[10] the trailer received positive feedback from those concerned with gender equality. Online, comments praising the action also demonstrated hope towards the new game, expecting a better share of importance to the female character. Rahna, an interviewee that first highlighted this issue, felt that the unexpected video spoke to her feelings: “I felt very emotional”. The use of Jennifer Hale’s voice gave her the sense that Bioware’s FemShep – or rather, her Shepard – was a canonical character and survived the fatal ending of Mass Effect 3, describing the experience as “thrilling”.

This is the opposite of what official material has done so far, where Male Shepard always ends up in the spotlight. Focusing on the female lead as the transition voice between the trilogy and the new universe of Andromeda is a response not only to fans’ complaints, but also to a social justice discourse that gained prominence since Mass Effect 3’s release in 2012: the call for diversity in the industry and creation of strong female leads. The decision evolved from a simple aesthetic change to appease the community, to one that is an integral part of the marketing strategy for the new game, putting women in the spotlight. Michael Gamble, producer of ME:A, responded to a fan discussion on Twitter about the marketing choices for the game, explaining that their strategy is to switch the main character for each trailer. Unlike the first trilogy, where the main character was Commander Shepard regardless of gender, the new game has two different main characters, known as the Ryder twins, to choose from: one male and one female. Although the actions available to the player for either gender are the same throughout the story, their twin will appear as a character you can interact with. Therefore, this apparent 50/50 divide in their marketing appearance is both a nod towards gender balance and the game’s proposal for the main characters.

Bioware’s official YouTube channel for ME:A posted 14 videos since the 2015 video with Jennifer Hale until the game’s release. Each main character has an equal number of appearances in these videos, with five videos for each character.[11] It is worth noting, however, that content-wise, Sara Ryder is more present in gameplay videos and the launch day cinematic trailer, while the male character, Scott Ryder, features in two “official cinematic reveal” trailers and the first official launch trailer, suggesting that despite their apparent equal status in gameplay, the female character is still being side-lined in favour of marketing discourses highlighting her male counterpart. This garnered some backlash from the community that wanted more Sara Ryder for the main advertising pieces. Discussions on the unofficial BSN forum said that “they fucked up her marketing, and now they have the audacity to show this poor, very short trailer when the game is already out and nobody cares about new promotional materials”; comments followed up with a comparison to the original games, stating that “femshep had better marketing.”[12] Some users calculated the exact time and amount of words that Sara and Scott Ryder had in these videos, with Scott being the first in both situations, contradicting the official discourse of gender parity in marketing. Other users however support Bioware’s marketing approach for ME:A, pleased that unlike FemShep, Sara does play a central role in advertising the game.

The choice to view the optional female main character in ME:A’s dominant marketing campaign points to the configuration of the company’s policy and strategies by the gamer community, no longer silent about the dominance of the imagined technomasculine public. This shift also reflects Maclaran’s (2015) claims of a current marketing practice that increasingly accounts for diverse masculinities and femininities. In an interview with Todd Philips from Eurogamer.net, vice-president of Bioware, Aaryn Flynn, emphasised that during the release of the first game they “drew inspiration from traditional marketing” – the one oriented towards the ‘mythic’ technomasculine demographic – but now believes that the whole videogames industry has moved beyond a traditional approach towards embracing diversity (Philips, 2016).

Conclusion

In the space of 10 years, Bioware’s marketing strategy has changed, configured by: a cultural sphere where the social discourses on gender are in constant (and rising) debate; by the action of players demanding more representation; and by the company’s need to adapt its discourse to attract a wider public and, consequentially, increased profit. As Condis (2014) demonstrates, Bioware’s inclusive policy is not purely out of a sense of social justice and progressive policies, but carries a strong financial need as well. The wider picture is more complex, as the current social context is marked by an intense clash of conservative and social justice discourses, so companies are forced to choose and defend a stance (see controversies such as GamerGate and activists like Anita Sarkeesian[13] as examples of this within videogames culture). For Bioware this is even more important as their public image is that of a progressive company that praises diversity rather than dismissing it. This broader context is highly influential in the configurative circuit, and the dimension of marketing explored in this paper is one of many examples of how these dynamics work in a process of mutual affectation.

These shifts in Bioware’s marketing strategy are configurative. The crucial role that the community of gamers played in this shift and their vocal discourse on social media configured the company’s own discourse about their female characters, Shepard and Sara Ryder. Players’ personal experiences continue to challenge the pre-conceived configuration of marketing and the company’s discourse. These complex dynamics are in tandem with the difficulties presented by Woolgar (1991) in the understanding (and acknowledgement) of the plurality of audiences by corporations. The shift to a partial female presence in Mass Effect 3 results from a set of configurative interactions between different nodes in the network of relations – namely, the different gamers, blogs, forums, Bioware employees, and others that participated in this reconfiguration process. The reverberation of this shift is felt in Mass Effect: Andromeda’s marketing campaign, which demonstrates the persistence of configurative interactions in the cultural sphere affecting decisions made in the medium-sphere, which may cause new configurations of play once the game is out. For instance, community pressure for more male same-sex romance within the squad made Bioware change the game months after its release to allow romance with squad-mate Jaal, a male alien character.[14]

The role of marketing in the configuration circuit remains true to its core purpose: to provide a channel for customers to understand the company’s goals and world view; to create and maintain a platform for its expanding consumer base; to sell a product or service; and to uphold a public reputation. However, once marketing is inserted into such a complex configurative circuit within videogames culture, marketing strategies do not, and cannot, work alone. It is a psychologically persuasive tool, and the claim for inserting a female lead in the campaign proves how persuasive it can be; people want to feel represented in the sphere of consumption where marketing operates. Consumption practices can be, to a certain extent, empowering to minorities but it is questionable, as Shaw (2014) argues, to what extent such representation within consumption practices is the one claimed by minority groups, or just a neoliberal response towards increase of capital. Maclaran’s proposal of a marketing practice that caters to a more diverse audience reflects both an academic and professional critique of a historically-biased approach to gendered marketing; but it also presents an opportunity to exploit those consumers by adhering to their expectations. On making FemShep and Sara Ryder more prominent, Bioware reinforces their public image of inclusiveness by nodding towards an often unheard audience, and taking a somewhat political stance in the context of GamerGate and the rise of conservative political forces worldwide. However, their strategic shift has its downsides as it has stirred anger among a more traditional community of gamers that constitute a considerable part of their profits. The different subjects in communication and their experiences in this configurative circuit seem to configure Bioware to their will, while simultaneously being enticed by Bioware’s public image as an inclusive company that creates videogames that respect diversity and are not – or at least, no longer – marketed only to an imagined technomasculine audience. In the case of Mass Effect, the subjects in communication that form its community, even in their clash of interests, ideologies, experiences, and desires, were capable of configuring back that which was imposed on them, the predilection for male heteronormativity. Whether said new marketing strategy will endure is unknown; but the configurative force of gamers in this circuit assuredly persists.

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, CNPq-Brazil.

References

American Marketing Association (2013), Definition of Marketing. Available from: https://www.ama.org/AboutAMA/Pages/Definition-of-marketing.aspx (Acessed 3 June 2017).

ADAMS, M. (2015), Renegade Sex: Compulsory Sexuality and Charmed Magic Circles in the Mass Effect series. Loading… The Journal of the Canadian Game Studies Association. 9 (14), 40-54.

ANTUNES E. & VAZ P. (2006), Mídia: um aro, um halo e um elo. V. FRANÇA & C. GUIMARÃES. Na mídia na rua: narrativas do cotidiano. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica.43-60

BURGESS, M. et al. (2007), Sex, Lies, and Video Games: The Portrayal of Male and Female Characters on Video Game Covers. Sex Roles. [Online] 57 (5-6), 419-433.

BUTLER, J. (1990), Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. New York: Routledge

CASSELL, J., & JENKINS, H. (1998), From Barbie to Mortal Kombat: Gender and computer games. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press

CONDIS, M. (2014), No homosexuals in Star Wars? BioWare, ‘gamer’ identity, and the politics of privilege in a convergence culture. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies. [Online] 21 (2), 198-212.

DEWEY, J. (2012), The public and its problems. University Park, Pa: Pennsylvania State Univ. Press.

______ (2005), Art as experience. New York: Berkley Pub. Group.

DOVEY, J. & KENNEDY, H. (2006), Game cultures. Maidenhead, Berkshire, England: Open University Press.

ESKELINEN M. (2004), Towards Computer Game Studies in Wardrip-Fruin, Noah and Harrigan, Pat (eds.) First Person: New Media as Story, Performance and Game. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2004

ESKELINEN, M. & TRONSTAD, R. (2003), “Video games and configurative performance”, in Mark Wolf & Bernard Perron (ed.) The Video Game Theory Reader. 1st edition New York: Routledge. pp. 195-220.

FISHER, H. (2015), “Sexy, Dangerous–and Ignored: An In-depth Review of the Representation of Women in Select Video Game Magazines”, Games and Culture. [Online] 10 (6), 551-570

FRANÇA V. and QUÉRÉ L. (2003), “Dos modelos da comunicação” [On the models of communication]. Revista Fronteira, vol 5, n.2 p. 37-51.

FRANÇA V. (2008), “Interações comunicativas: a matriz conceitual de G. H. Mead” [Communicative Interactions: the conceptual matrix of G.H. Mead.] in: A. Primo, A. Oliveira, A. Nascimento and V. Ronsini (ed.). Comunicação e Interações. Porto Alegre, Ed. Sulina p. 71-91.

______ (2006), “Sujeitos da comunicação, sujeitos em comunicaçã”, in: V. França & C. Guimarães. Na mídia na rua: narrativas do cotidiano. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica. 61-88

GIBSON, J. (1979), The ecological approach to visual perception. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

GOFFMAN, E. (1961), Encounters. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill.

______ (1987), Gender advertisements. 1st edition. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI.

HAMILTON, K. (2011), “Fans Picked the Blonde in a Controversial Video Game Beauty Contest, But That’s Not a Bad Thing”, Kotaku, Available at: http://kotaku.com/5826702/fans-picked-the-blonde-in-a-controversial-video-game-beauty-contest-but-thats-not-a-bad-thing.

HARVEY, C. (2015), Fantastic transmedia: narrative, play and memory across science fiction and fantasy storyworlds. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

HEINEMAN, D. (2015), Thinking about video games: interviews with the experts. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

IIJIMA HALL, C. & CRUM, M. (1994), “Women and “body-isms” in television beer commercials”, Sex Roles. [Online] 31-31 (5-6), 329-337.

IVORY, J. (2006), “Still a Man’s Game: Gender Representation in Online Reviews of Video Games”, Mass Communication and Society. 9 (1), 103-114.

JOHNSON, R. (2013), “Toward Greater Production Diversity: Examining Social Boundaries at a Video Game Studio”, Games and Culture. [Online]

JUUL, J. (2005), Half-real: videogames between real rules and fictional worlds. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

KERR, A. (2006), The business and culture of digital games. London: SAGE.

KLINE, S. et al. (2003), Digital play: The interaction of technology, culture and marketing. Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

KOCUREK, C. (2015), Coin-operated Americans: rebooting boyhood at the video game arcade. 1st edition. Minneapolis – London: University of Minnesota Press.

LEONARD, D. (2006), “Not a Hater, Just Keepin’ It Real: The Importance of Race- and Gender-Based Game Studies”, Games and Culture. [Online] 1 (1), 83-88.

LIEN, T. (2013), “No girls allowed: Unraveling the story behind the stereotype of video games being for boys.” Polygon, Available from: http://www.polygon.com/features/2013/12/2/5143856/no-girls-allowed

LIMA, L. (2017a), “O potencial político dos videogames para o debate sobre gênero e sexualidade”, Revista Fronteiras. [Online] 19 (1), 129-143.

______ (2017b), “Videogames as a political medium: the case of Mass Effect and the gendered gaming scene of dissensus”, in: Tosoni et al. Present scenarios of media production and engagement. Bremen: Edition Lumière. pp. 67-80

MACLARAN, P. (2015), “Feminism’s fourth wave: a research agenda for marketing and consumer research”, Journal of Marketing Management. [Online] 31 (15-16), 1732-1738.

______ (2012), “Marketing and feminism in historic perspective”, Journal of Historical Research in Marketing. [Online] 4 (3), 462-469.

MEAD, G. H. (1934), Mind, self & society from the standpoint of a social behaviorist. Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press.

MOULTHROP, S. (2004), “From Work to Play”, in Wardrip-Fruin, Noah and Harrigan, Pat (eds.) (2004) First Person: New Media as Story, Performance, Game. Massachusetts: MIT Press

MURRAY, J. H. (1999), Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. Massachusetts: MIT Press

PHILIPS, T. (2016), “Why BioWare showed Mass Effect Andromeda’s female hero first”, Eurogamer.net, available at: http://www.eurogamer.net/articles/2016-06-24-why-bioware-showed-mass-effect-andromedas-female-hero-first.

QUÉRÉ, L. (1995), “From an epistemological model of communication to a praxeological approach”, Reseaux. The French Journal of Communication, vol. 3, n. 1, pp. 111-133

______ (2003), « Le public comme forme et comme modalité d’experience », in Cefai, D; Pasquier; D. Les sens du public, publics politiques, publics médiatiques. Paris: PUF. pp. 113-134.

RYAN, J. (2011), Super Mario. New York: Portfolio Penguin.

SARKAR, S. (2015), “Mass Effect’s Commander Shepard was created as a woman”, Polygon, available at: http://www.polygon.com/2015/1/9/7520965/mass-effect-commander-shepard-woman-animation.

SHAW, A. (2014), Gaming at the edge: sexuality and gender at the margins of gamer culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

______ (2009), Putting the Gay in Games: Cultural Production and GLBT Content in Video Games. Games and Culture. [Online] 4 (3), 228-253.

SLABAUGH, B. (2013), “See how your Mass Effect choices compare to everyone else’s”, Escapist Magazine, available at: http://www.escapistmagazine.com/news/view/122880-See-How-Your-Mass-Effect-Choices-Compare-to-Everyone-Elses

THORNHAM, H. (2008), “It’s A Boy Thing”. Feminist Media Studies. [Online] 8 (2), 127-142.

WILLIAMS, D. et al. (2009), “The virtual census: representations of gender, race and age in video games”, New Media & Society. [Online] 11 (5), 815-834.

WOLF, M. (2008), The video game explosion. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press.

WOOLGAR, S. (1991), “Configuring the User: the Case of Usability Trials” in Law, John (ed) (1991) A Sociology of Monsters: Essays on Power, Technology and Domination. London: Routledge

Leandro Augusto Borges Lima is a PhD candidate at King’s College London, department of Culture, Media and Creative Industries, recipient of a CNPq/Brazil scholarship. His research explores the uses of videogame as a medium for political conversation, focusing on matters of gender and sexuality through a case study of the game Mass Effect.

Notes

[1] Canon is a term used to describe stories, plots, characters, and events officially accepted as part of a certain universe’s story.

[2] Mass Effect 1: http://masseffect.bioware.com/me1/ ; Mass Effect 2: http://masseffect.bioware.com/me2/; Mass Effect 3: http://masseffect.bioware.com

[3] https://www.youtube.com/user/biowaremasseffect

[4] Due to the timeframe of this research, several tweets were likely lost either from deleted accounts, privacy policies adopted by users and the lack of proper resources to collect older tweets. Nonetheless, the volume of tweets collected is significant for the purposes of this paper.

[5] Geographical limtations were an issue due to budgetary constraints. Therefore, despite the questionnaire being open to anyone, the selected interviewees were mainly from two Brazilian cities – Belo Horizonte and Rio de Janeiro – and London.

[6] Mass Effect website, available at: http://masseffect.bioware.com/me1/gameinfo/index.html

[7] A head-canon is when an individual has his/her own readings or elements inserted into a fictional universe that are unsupported by the official canon.

[8] Source: http://www.escapistmagazine.com/news/view/122880-See-How-Your-Mass-Effect-Choices-Compare-to-Everyone-Elses

[9] A ‘cookie’ is sarcastic slang utilised when a person, institution or company wants to be praised for something they did. Often used when they behave accordingly to a certain politically correct agenda, but do it poorly or with secondary intentions other than actual support.

[10] To celebrate the fifth anniversary of Mass Effect’s release, Bioware created N7 Day, a day of celebration for the fans, annually celebrated on the 7th of November since 2012. Bioware commemorates N7 Day by providing fans “everything from online events, in-game rewards, behind-the-scenes peeks, N7 Day exclusive assets, and much, much more!” Since its first occurrence, every N7 day is met with expectation regarding big announcements for the Mass Effect franchise. Source: http://masseffect.bioware.com/community/n7day/

[11] Four videos had secondary characters and one of those focused on an important female non-playable character, Dr. Lexi T’Perro, voiced by Game of Thrones actress Nathalie Dorner. She was the only other character to have a video of her own on the YouTube channel.

[12] Source: http://bsn.boards.net/post/454803/thread

[13] https://feministfrequency.com/

[14] Source: https://www.pcgamesn.com/mass-effect-andromeda/mass-effect-andromeda-jaal-male-romance