Volume 5, Issue 1, December 2015

Douglas Schules

Rikkyo University

Abstract

Despite frequent reference in academic and fan work to the video game genre known as JRPG (Japanese role-playing game), little critical scholarship has been dedicated to understanding how to conceptualize the genre. Frequently, JRPGs are framed as a cultural curiosity, with the “J” operating as a cultural appendix to established and well-defined genre of RPGs. The coordination between government and industry central to soft power, however, offers insight into the construction of the genre by highlighting the role the market plays in promoting culture. Drawing from representations of and discourse about gender in the MEXT’s Cool Japan campaign, this paper argues that JRPGs should be framed as one elemental part of a larger creative ecology that comes to define Japan and its culture overseas.

Keywords: creative ecologies, Japanese Role-playing games (JRPGs), kawaii, media mix, soft power

Résumé en français à la fin de l’article

*****

Introduction

Few gamers would dispute that Tales of Xillia, the game from which Video 1 comes, is a role-playing game (RPG). It has all the trappings of the genre: randomness, quantification of characters, and a leveling system (Wolf, 2002). Most would further say that it is clearly a Japanese role playing game (JRPG), using a common fan term to describe the gaming experiences players encounter when playing this certain genre of video games from Japan.

The source of these differences, what ostensibly constitutes JRPG as a genre, however, remains a point of debate. For fans, the genre is typically framed as a foil to Western role-playing games (WRPGs), locating the differences between the two in some alchemical arrangement of narrative (story engagement), aesthetic (visuals), and ludic (sandbox vs. confinement) properties (doady, 2012, November 10; Extra Credits, 2012; Gyyrro, 2012, September 12; Ross, 2012, January 29; Weedston, n.d.). While video game historian Matt Barton (2008) references these as elements of the genre, he also argues that understanding JRPGs necessitates charting the country’s political, ideological, and cultural currents. If Tales of Xillia is an RPG by virtue of sharing certain gaming mechanics compositional to role-playing games, what makes it Japanese is plausibly located elsewhere.

Academic approaches to the subject have been mixed. While there is a small but growing literature using JRPGs, there is a significant gap in critical work about them. Building upon the insights of Darley (2000) and Azuma (2009), Glasspool (2013) notes that conceptualizing JRPGs as simulations of Japan and Japanese culture is useful not only for understanding how discourses about them are constructed, but also how these discourses circulate across and are transformed through media. The emphasis on the circulation of discourse across media in many ways parallels Marc Steinberg’s (2012) theory of the media mix, where synergy across media reinforce the narrative worlds formed by the Japanese creative industries to sell creative media. Approaching JRPGs in their capacity as creative media artifacts, then, offers an opportunity to understand the genre in relation to the systems of production and circulation in which they are a part, an important step in understanding how discourses of the country and its culture are consumed as well.

To that end, this paper takes Barton’s suggestion to heart by building off Steinberg’s concept of the media mix to position JRPGs within the larger media ecologies surrounding the creative industries. These industries are given a thoughtful, if unflattering, examination in Critical Theory, which examines the impact of the commodification of culture. The networks of production and consumption central to these processes inform not only the concept of the media mix, but form the basis of Joseph Nye’s (2005) theorization of soft power. The Cool Japan campaign, one ongoing Japanese exercise of soft power, presents a useful place to trace these relationships given the variety of media it brings together under its banner. Through traditional and new media, the campaign highlights how « distinctive » Japanese concepts are embodied in traditional and contemporary Japanese goods, thereby facilitating the commodification of Japanese culture. One of the more successful themes in the campaign has been the articulation of kawaii, or cute, as a representation of the culture, although the objective of Cool Japan as a branding tool ensures that only certain facets of kawaii—and certain media using those sanctioned facets—get exposure. Within this framework I argue that when speaking of the circulation of Japanese creative media such as JRPGs, particularly overseas, we should speak of a cultural media mix wherein the coordination between government and industry reinforces a cultural ecology premised on the consumption of commodified narratives across media objects. As a commodity in the cultural media mix, kawaii is thus fragmented into various parts, necessitating consumption across media to reconstruct the overall cultural narrative of Japan.

While Japanese games appear sporadically in the pages of the campaign’s official governmental publications, JRPGs still serve as a useful way to explore the vagaries of the cultural media mix because of their popularity and their capacity through downloadable content (DLC) to embody multiple representations important to the projection of soft power overseas. Focusing on the narrative of kawaii in Cool Japan, I explore how cuteness is constructed, and the implications of this construction, in JRPGs. Specifically, I examine scenes from the PS3 titles Tales of Xillia (2011) and Tales of Graces f (2010), having chosen this series because of its length (Tales of Phantasia, the first game in the series, was released for the Super Famicom in 1995) and its popularity (excluding Tales of Xillia 2, the series has sold over 13 million copies worldwide (Sony Computer Entertainment Inc., 2011). These titles are additionally useful due to their extensive use of DLC in the form of costumes, facilitating the circulation of—and engagement with— discourses about Japan and its culture compositional to the cultural media mix.

This essay is divided into three major sections. I begin with a theorization of the cultural media mix, linking the ecologies of production and consumption of the media mix to the operations of soft power and the commodification of culture. Next, I sketch the importance of video game DLC to these commodification processes as they relate to soft political discourses of and about Japan. Finally, I analyze the significance of these processes framing kawaii in the Cool Japan campaign, paying particular attention to its articulation of gender.

The Cultural Media Mix: Creative Media and the Japanese Brand

At the heart of the media mix are relationships. Originally developed to describe marketing practices, Steinberg (2012) argues that the term has become increasingly associated with practices of narrative circulation developed by the Japanese creative industries to promote anime. In this anime media mix, characters and the worlds they inhabit are developed across media with the goal of creating a media world wherein the consumption of one element drives the consumption of others (Steinberg, 2012, p. 141).

Eiji Ōtsuka’s (2010) theory of narrative consumption aids in this process by offering insight into one way this synergy is achieved. Rather than emphasizing the structural networks linking media objects together, narrative consumption—as the name implies—focuses on the role stories play in driving the consumption of discrete media. Motivating this consumption is the character-world relationship, where a grand narrative (or worldview) structures how smaller ones known as narrative fragments fit together.

These processes discussed by both Steinberg and Ōtsuka reflect the systems of relation central to the culture industry, which link the mass production and distribution of creative media to the commodification and homogenization of culture (Cook, 1996, p. 37). Like the relationships between media discussed by Steinberg or those across narrative fragments raised by Ōtsuka, the mass production of culture through creative media creates an interlocking system in which « each branch of culture is unanimous within itself and all are unanimous together » (Horkheimer & Adorno, 2002, p. 94). For Horkheimer and Adorno each “branch of culture” refers to media industries such as film and music, and the uniformity they create a function of how these forms rely on generic tropes or styles to structure a homogenous experience. Hollywood blockbusters, for example, generally adhere to a similar, predictable narrative structure that appeals to the largest audience possible. In terms of Japanese creative media, shōnen manga[1] like Fairy Tail or Magi adhere to a series of tropes wherein one title is nearly indistinguishable from another, while JRPGs deploy a standardized epic narrative wherein teenage-village-boy-leaves-hometown-and-saves-world. But such homogeneity occurs across these “branches of culture” as well, the result of neoliberal relaxation on ownership restrictions that allow companies to own media across industries. Through the media mix and strategies such as narrative consumption it is more useful to consider these “branches of culture” in terms of corporate spheres of influence, particularly considering the organization of the Japanese creative industries.

As the culture industry locates the production of culture in creative media, the ecologies in which they circulate—such as those of the media mix—also become ecologies of cultural circulation. It is in this context I would like to re-conceive of the character-world relationship as an element of a cultural media mix of which JRPGs are a part, although it requires an additional player invested in the circulation of creative media in their capacity as cultural exemplars. The theory of soft power (sometimes referred to as soft culture) is useful in this regard, as it already frames culture as a commodity whose real value lies in its ability to be exchanged to further political or social agendas.

According to Nye, soft power is « the ability to establish preferences [based on] intangible assets such as an attractive personality, culture, political values and institutions, and policies » rather than through force (Nye, 2005, p. 6). The aim of soft power is not to highlight one specific aspect of a country, but instead create a positive atmosphere surrounding it, a feat best accomplished through coordination between government and industry. Kenjiro Monji, former Director-General of the Public Diplomacy Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA), offers a glimpse into the logistics of this power when he asserts that “the wellspring of such soft power lies in the private sector, so any attempts to exercise this power at the national level should be premised on working closely with the private sector” (« Coordinated efforts to share Japanese culture, » 2009, p. 13). Through the Cool Japan campaign, Japan accomplishes this by drawing together resources in the creative industries, technology sector, culinary arena, and fine arts traditions to create a Japanese brand it projects overseas (Chiba, 2003; Daliot-Bul, 2009; Graves, 2012; Nye, 2005; Storz, 2008).

The coordination between government and industry invests the culture industry with a geographic dimension wherein (perceived) production-location plays a role in the authenticity of creative media to embody culture. Associating production-location with cultural expression allows for subgenres based on perceived cultural characteristics to be carved from existing genres. Within gaming, this only seriously applies to JRPGs—The Witcher or Gothic series are not described as PRGPs or GRPGs in homage to their Polish and German origins—as the Japanese qualifier taps into Orientalist discourses of the country’s cultural uniqueness (Gluck, 1985). The idea that a product reflects cultural values contingent upon its connections to Japan can be traced at least to discourse circulating in the Meiji era (historical examples can be found in Beale, 1888; de Wyzewa, 1890; Gardener, 1895; Lowell, 1887), with contemporary manifestations equating the consumption of creative media to understanding, in the words of former Japan Foundation President Kazuo Ogōra, “the Spirit of Japan through its arts and culture” (« Culture as a global asset, » 2009, p. 23).

By accentuating the centrality of production-location to the identity of Japanese creative media, soft political exercises such as Cool Japan direct the logic of commodification central to the culture industry to empower the country’s economic position. The coordination between government and industry central to soft power accomplishes this by locating the country’s culture in narrative fragments across multiple media and media platforms. The processes of commodification, however, complicate matters by additionally investing the media object, not just its content, with the status of cultural object. Culture is simultaneously a material thing (e.g. anime, manga, JRPG) and an idea (e.g. wabi-sabi, kawaii). The complexities of these relationships spanning the modes of production, circulation, and consumption across media within the context of soft power are what I mean by the cultural media mix.

Downloadable content: gaming the media mix

Approaching creative media from the spaces they occupy as commercial products presents one way to map the relations between commodities and soft political discourses about them. In this regard, video games offer an important contribution to the formation of the cultural media mix because, unlike other creative media such as anime or manga, they can be easily adapted or altered after production to accommodate new narrative fragments.

While little academic work has been done on DLC, there is a body of literature on gaming modifications, or “mods,” that is useful in understanding its significance to games. Mods are “player-made alterations and additions to preexisting games” (Sotamaa, 2010, p. 240) that “can range from minor changes in the physics of the virtual world to total conversions in game play” (Postigo, 2007, p. 301). Such alterations offer players new ways to experience games by introducing additional challenges, characters, or even storylines to games. The mid-2000s saw the application of this concept to gaming consoles through the development of online stores such as Sony’s PlayStation Network (PSN), Microsoft’s Xbox Live Marketplace (XBLM), or Nintendo’s Wii Shop Channel. These stores, in conjunction with the increasing penetration of broadband technologies, allowed for the online distribution of games and related resources that collectively has come to be known as downloadable content (DLC). One common type of DLC is aesthetic, allowing players access to additional costumes, equipment, or other assets not normally included in the original game and which players can use to tailor the visual game experience to their own preferences.

There are some significant differences in the media ecologies of mods and DLC. First, while the producers of mods are typically fans or groups not affiliated with the developer of the title in question, DLC is produced by the original developer. Second, while mods are distributed through a variety of Internet channels, DLC is distributed through the official stores of each respective console. The proprietary software on which these consoles run makes it difficult for unofficial modifications to be executed. The closed ecosystems of the stores through which DLC is primarily acquired additionally makes it difficult for technologically uninclined fans to access and install these modifications. As a result, it appears that developers have slightly more control over the medium with respect to fan appropriation and alteration of content compared to other creative media.

In terms of the cultural media mix, however, the significance of DLC lies with its potential to restructure aspects of the gaming experience by changing how players perceive the diegetic space. In speaking of the relationships between narrative and game structuring, Juul (2001) mentions that while the narratives and gameplay across players of the same game will be roughly similar (excepting localization issues, which is a matter for another time), the interpretation or framing of these elements vary. Multiple players playing the same game, then, will interpret it differently based on their individual configuration of the gaming elements. This can be attributed to a variety of causes, although differences in players’ technical skills and background knowledge contribute to how their experiences are structured. Common examples include downloadable costumes that refer to other popular games or shows. Final Fantasy XIII-2: Lightning Returns, for example, includes costumes from previous games in the series, as well as other Square-Enix properties like Tomb Raider; potential DLC for Tales of Vesperia likewise includes costumes from other games in the Tales series, but the strangest is a costume from the anime Keroro Gunsō (Sergeant Frog),[2] seen in the after battle sequence of Video 2.

As a general practice, costumes do not alter in any significant way the gameplay or narrative of their respective games. Rather, the ability of these costumes to restructure a player’s gaming experience stems from their semiotic connections to other games. While these connections naturally rely on a player’s background knowledge and familiarity with the game being referenced, it is important to recognize that the types of costumes available as downloadable content frequently draw from properties either owned by the companies themselves or one of their parent companies. Although it is no surprise that the Final Fantasy or Tales games contain costumes from other games in their respective series, the availability of the keroro gunsō costume in Tales of Vesperia remains an enigma until we realize that Sunrise, the producer of the anime, is owned by umbrella company Bandai-Namco. Even the publisher of the original manga, Kadokawa, owns a stake in Bandai-Namco holdings. These connections across media properties parallel the practices of the media mix, with a player’s consumption of a company’s other creative media expanding the possible ways in which they can frame, and hence experience, the game.

As an element of the cultural media mix, however, costumes become additionally invested with the potential to reconfigure the gaming experience based on a player’s familiarity with Japanese cultural flows. As Jun Takeuchi says, « Because we market our video games to people from countries throughout the world, there’s this assumption that we design them on the basis of appealing to everyone, everywhere. But actually, that’s not the case. We make a conscious effort to create video games that will introduce foreign gamers to uniquely Japanese concepts and sensibilities. » (« Taking video games to the next level, » 2009, pp. 18-19). DLC provides one avenue for players to experience this Japanese “uniqueness” by embodying narrative fragments used in soft political discourse to project specific visions of the country overseas.

The extent to which the coordination between government and industry successfully draws together production-location, culture, and media object in branding Japan is best demonstrated through the words of the founder of The JRPG Club, a forum for players interested in the genre:

I consider a JRPG to be a game that was originally developed and released in Japanese. Even when Western developers try to make something « Japanese » or vice versa, there will always be aspects of the original culture informing the material contained within. A Western take on a JRPG (which makes up most of indie RPG development right now) or a Japanese take on the WRPG (Dragon’s Dogma, Dark Souls) wouldn’t necessarily change a game’s genre, nor would games that are designed with international release and easy localization; look at someone like Murakami Haruki, who writes with the English translation in mind. No one would say that his writing isn’t Japanese. (cappazushi, 2013)

While this position does not accurately reflect the reality of production in a global market (see Consalvo, 2006), it does indicate the extent to which geographic considerations underlying soft power become enmeshed with the commodity quality of creative media. To originate in Japan implies that a product is somehow invested with a fragment of the country’s culture, a characteristic so intrinsic that it even applies to products imported into the country. “When Japan imports something from overseas,” according to Kazuhiko Tsutsumi of NHK Enterprises, “adjustments are made to cater to Japanese tastes. These twists…strike foreigners as being very Japanese—and very cool. » (« »Cool Japan » goes global, » 2009, p. 21). JRPGs are seen as following this trend by adapting earlier CRPG (computer role-playing game) series like Wizardry and Ultima with Japanese cultural elements. One of these « twists » or adaptations indicative of Japanese-ness in RPGs is the distinct visually aesthetic style, of which « kawaii » plays an oversized role (see Kohler, 2004).

Kawaii Japan: Branding in the Cultural Media Mix

Literally « cute, » kawaii is popularly associated with physical characteristics such as large eyes or smallness, or behavioral traits such as childishness or innocence. Academic work on the subject has explored how these impact politics (Chuang, 2011; Katō, 2006; Yang, 2010) and gender (Hasegawa, 2002), with Laura Miller’s work (2011a, 2011b) on Cool Japan useful in explaining how gendered systems of power guide the representation of females in the campaign. Her argument that only certain, highly gendered, aspects of kawaii are promoted in the campaign comes into sharper focus if we approach “cuteness” as commodity. In speaking of the commodification of kawaii in Hello Kitty, McVeigh (2000) argues that central to this process is the investment of discourses of cuteness (what he calls “a sort of fundamental aesthetic of the everyday” p. 230) in a variety of forms across material objects. In this section, I will examine how behavioral practices inform different variations of kawaii and how these are represented across characters in Tales of Xillia. These differences are then framed in terms of their relation to the character-world system, where their ability to reconstruct the cultural narrative of kawaii, let alone the grand cultural narrative of Japan, is questioned.

An examination of magazines, expos, and other Cool Japan campaign publicity strategies reveals that kawaii serves as one soft cultural theme to promote the country and its culture. In 2009, the campaign linked kawaii to various fashion trends in Japan and aggressively promoted this through the expos and events they helped sponsor overseas. To more efficaciously accomplish its goals of promotion, the campaign gave human faces to these fashion trends by appointing “kawaii ambassadors,” young women who promote these fashions through a combination of modeling the styles, holding conversations about them, and offering tips to improve ensembles. The kawaii ambassadors represent three specific Japanese fashion communities: Harajuku fashion, school girl uniform fashion, and Lolita fashion.

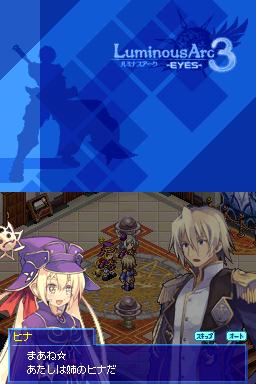

These styles frequently appear in the Tales series and other JRPGs, as both DLC and original character skins (Figures 1 and 2).

Elise, the girl wearing the black dress, sports a variation on Lolita fashion known as Gothic-lolita, or goth-loli for short. According to Misako Aoki, the Kawaii Ambassador of Lolita fashion, “It’s a style that incorporates lots of laces, ribbons, and frills—things that girls really have a fondness for” (« Japan’s pop culture broadens its international reach, » 2009, p. 11). These visual cues associate Elise to the concept of kawaii, although visual styles, of course, can be imitated. But the seduction of Cool Japan lies with the campaign’s ability to conflate culture and production-location by tapping into and recirculating discourses about the country’s cultural uniqueness. More than merely identifying visual tropes, they need to be meaningfully connected in the international imaginary with Japan. This position seems to have traction given the perception, common in fan communities and articulated concisely here by founder of The JRPG Club, of the importance culture plays in shaping representations in creative media:

[I]magine a European-made RPG, or some piece of European literature. By its very nature of being produced by someone with different cultural backgrounds than those writing or programming in the US, an ERPG would probably be, at some level, easily distinguishable from a USARPG.

In Japan, the differences are even more pronounced; the cultural divide between the West and East is much more pronounced than the one between the different regions that are considered part of « the West. » Furthermore, Japan is still a relatively untouched culture due to its history of isolation and homogeny, which in some respects continue to this day. Because of that, recognizing some piece of art or media as « Japanese » is not that difficult. (cappazushi, 2013)

While the global commodification of cute makes identification of Harajuku, schoolgirl, and Lolita fashions rather easy (Miller, 2011a, pp. 22-23), the styles reflect broader ideologies about gender and behavior essential to kawaii. More than a visual form, understanding kawaii necessitates understanding how discourses about it fit together across media and link with other discourses of and about Japan. Inuhiko Yomota’s (2006) book Cute Theory (Kawaii Ron) is informative in this regard as it recognizes that kawaii comprises a number of divergent practices while simultaneously providing a genealogy of their development.

The scene with Elise fits the profile of what Yomota identifies as a strain known the child-like (kodomorashisa). Although Elise looks like a child, it is not necessarily her appearance that makes her cute. Rather, these visual cues tap into a larger set of expectations with respect to her behavior and the viewer’s position to it. What makes the child-like cute are its associations with innocence and purity. In what could be termed an aesthetic of potentiality, the child-like is additionally cute due to the pleasure the viewer derives from imagining the possible futures of that which one is viewing. While one of the central flaws in his discussion of this subject is the absence of critical analysis in fleshing out his claims, Yomota advances these claims through the example of the kabuki drama Shiranami Gonin Otoko (lit, The Five Men of the White Waves). Here, he argues that versions of the play purposefully cast boys in the lead roles to capitalize on the idea of potentiality inherent in childishness wherein “Japanese people enjoy imagining the future when these boys will become adults and proud actors” (Yomota, 2006, p. 122). Underlying Yomota’s framing of the child-like is a generic Buddhist world-view wherein innocence and purity are essential characteristics of children. Through experience, we become inured to the suffering of others and develop attachments; it is the world and experience in it that corrupts, and children, by virtue of their age have not yet been « tainted. » In this fashion, viewing that which is child-like produces a sense of pleasure at imagining the possibilities available to the object under consideration, not unlike Kant’s theorization of pleasure derived from the free play of imagination.

To understand Elise’s cuteness in the scene, we need to know a little bit more about her character and the context of the scene. Briefly, Elise is a 12 year old girl who possesses a gift for summoning magic. At an early age, her parents were murdered and shortly thereafter she was taken to a research facility where she became the subject of experiments. The isolated environment and lack of significant human interaction forced her to create a companion in the form of Tipo, the floating purple bean-like thing seen next to her. Tipo acts as her psychological guardian and sometimes id, serving as a proxy through whom she articulates sarcastic comebacks and inappropriate comments. Elise’s fractured psychological state is not revealed until the middle of the game; until that point the two characters are framed as separate, albeit interdependent, ones.

What drives Elise’s cuteness is her lack of concern for the gravity of the situation, instead focusing on her own needs. While Tipo is the one who exclaims that he is hungry, at this point in the game both the player and the party are aware of Elise’s psychosis, so everyone involved recognizes that she is the one who is making the statement. The party turns to her, and she blushes. It is her psychosis that drives her cuteness, as she is able to deflect any behavior outside the scope of our expectations on cuteness to her proxy; that she continues to do this even when her secret is revealed is cute in and of itself due to the innocence of trying to maintain appearances. Her blushing indicates that she realizes the ploy has failed, a child caught, as it were, trying to shift blame to the cat for breaking the expensive china. Given the gravity of her past, Elise’s psychosis operates as a way for her to exhibit the behavioral traits expected from this form of kawaii, signaled by the visual cues of her character and costume.

We must keep in mind, however, that it is behavior that drives kawaii. Milla, one of two main characters players can select to when starting the game, fits the child-like profile because of her actions rather than physical form (Figure 3).

Playing as her in the prologue to the game, we quickly note that her abilities significantly exceed those of our opponents. We discover that she is the reincarnation of Maxwell, a savior-like figure in the game world who controls the four great elemental spirits, here to stop the mechanizations of an evil empire. As the prologue concludes, however, she is struck by a weapon that divests her of all her power, and separates her from the great elemental spirits.

Milla’s purity, so to speak, emerges in various points across the game narrative as she experiences aspects of life for the first time without help from her elemental guardians. Her helplessness at wielding a sword becomes a narrative plot device, and extra narrative events known in the series as « skits » occur at various points in the game to discuss her first experiences of being hungry (sustenance was provided by the earth spirit Gnome), tired (the spirit Sylph eased her fatigue), and so on with other little mundane experiences.

In game terms, she is rendered back to level one and stripped of all her skills and abilities. Her cuteness, following Yomota’s logic, emerges from the player’s projection of her potential—that she will once again become this powerful and perhaps more so by endgame. The gender dynamics operating here are significant, as the same situation happening to Jude (it doesn’t) would not be « cute ».

As a slice of the larger cultural media mix promoted by Cool Japan, this one game demonstrates the variability in tropes used to advance the campaign. In this one Tales game, we have the same trope operating differently in different characters. Relying on Elise or Milla alone to base an understanding of kawaii, however, produces an underexposed picture. A longer exposure of kawaii across JRPGs reveals other details, some of which do not fit into the category of the child-like just discussed. In fact, it appears that kawaii can be expressed in multiple visual and behavioral forms. Consider the following examples in Figures 4 through 7:

Each of these screenshots speaks to a different version of cuteness Yomota identifies and visible across Japanese creative media. That each of these images represents kawaii differently reflects values within both specific communities in Japan and the public sphere. This heterogeneity aids the cultural media mix envisioned through Cool Japan by pre-packaging its culture into multiple, autonomous lifestyle fragments that can be united through media consumption. Each individual expression of kawaii appearing in a medium, in other words, functions as a narrative fragment containing a sliver of the discourse about that particular type of kawaii. Tales of Xillia is by no means the only JRPG to flirt with the trope of the child-like. The multiple variations of kawaii additionally compound representative plurality; coupled with the continued production of creative media which utilize these representations and the ever evolving nature of popular culture, completing the narrative is nothing short of a Sisyphean task.

The medium, essentially, becomes a lens thorough which fragments Japanese culture, in this case kawaii, can be divined by the trained eye. Being able to identify and reassemble the narrative fragments conveys (sub)cultural capital, where possessing this specialized knowledge can be exchanged for prestige or status within the proper communities (see Bourdieu, 1984; Thornton, 2005). That knowledge of the character-world relationship comprising the cultural media mix functions as a commodity is really a symptom of the evolving role exchange value plays in the culture industry. As it matures, « the culture industry no longer even needs to directly pursue everywhere the profit interests from which it originated. These interests have become objectified in its ideology and have even made themselves independent of the compulsion to sell the cultural commodities which must be swallowed away. » (Adorno, 2001, p. 100). The pursuit of profit underlying the commodification of culture, in other words, integrates into broader societal ideologies wherein its coercive power becomes sublimated to less overt and more appealing forms. In their capacity as soft political tools, Japanese creative media function as ambassadors whose value lies in their ability promote positive interest in the country and the Japanese brand. The development of hierarchies wherein knowledge systems about Japan, its culture, and its popular media drive consumption practices and vice-versa, of which otaku culture seems most (in)famous, charts these processes. The sublimation of commodification is significant, as it elevates the processes of exchange central to the commodification of culture from tangible material goods to intangible systems of relations surrounding it.

Kawaii in this sense functions in a similar way with respect to understanding the « world » of Japan it presumably represents: in order to complete the narrative of kawaii, itself only one component of the cultural content comprising the larger world of Japan, consumers must constantly play games in which different versions of the concept are articulated. Elise’s costume signifies a play on kawaii and guides our expectations, but it represents one facet of how the trope can be expressed. The concept of kawaii therefore functions across media in multiple ways, with no specific game or anime containing representations of all possibilities. As a result, in order to « complete » the kawaii narrative, fans must constantly pursue and consume representations in other media—JRPGs or otherwise—to make sure their account matches that of the larger whole. Parallel to the theory of narrative consumption (Steinberg, 2012, p. 182), the cultural narrative can never be completed because the creative industries are constantly releasing new products which tap into and refine how the discourse is articulated.

Video game DLC offers a prime example of this process through its ability to restructure the gaming experience. In addition to the cosmetic alterations previously discussed, DLC can also easily add additional content to the game. One hallmark of the Tales series, for example, has been after battle dialogue. After each victory, the characters who participated in the battle interact with each other; DLC can change these dynamics by injecting different narrative fragments into the game, as shown in the Video 3 and Video 4:

The addition of the idol costumes for the female players produces a different visual approach to the after battle dialogue. In order to trigger this variant dialogue, all of the female characters must wear the costume. The close-ups on their faces coupled with the surreal appearance of stars as they pose for the camera are meant to invoke the kawaii associated with the Japanese phenomenon of purikura, photo booths that allow people to alter the photos taken of them by adding frames, sparkles, and a host of other aesthetic choices. DLC enables players to draw from and engage with the various narratives about Japan and its culture articulated in Cool Japan, offering a platform from which players can experiment with the cultural tropes linked across Japanese media. In so doing, DLC offers a digital modification to the “interplay” McLuhan (1994, p. 240-241) states is essential to games.

Unfortunately, despite the ability of players to alter some aspects of games and experiment rearranging narrative fragments, there is little opportunity for them to resist, reconstruct, or challenge these narratives. Much like Miller suggests regarding how the commodification of femininity prevents challenging gender roles in Cool Japan, the limited fragmentary resources from which players can draw, coupled with their inability to actually restructure the gaming world, are confined by the commodification of culture.

Conclusion

While JRPGs share the same ludic traits with RPGs, what constitutes the “J” of genre remains harder to pin down. While at times defined in terms of their aesthetic traits and at others in terms of their narrative or even ludic dimensions, in this article I have argued that one way to understand the Japanese qualifier of JRPGs is through its position in a larger framework of creative media brought together under the aegis of soft power. Despite soft political discourse to the contrary, JRPGs are Japanese not because of any intrinsic quality they possess; rather, they are Japanese by virtue of their relation to other creative media.

The commodification of culture that appears through the exercise of Japanese soft power, witnessed in the Cool Japan campaign, charts these processes. Building upon the character-world relationship of narrative consumption, cultural elements such as kawaii are treated as characters in a larger world constructing the country, one that can only be completed through consumption across multiple creative media. In this cultural media mix, each discrete element in the network contains a portion of the grand cultural narrative that consumers are challenged to assemble through fragments found across multiple media, genres within these media, and individual differences between objects of the same genre. Kawaii, for example, appears in Cool Japan magazines as an expression of gendered fashion, and although these appear in Tales of Xillia kawaii is framed more prominently in terms of behavioral traits.

Like the media mix, this cultural media mix is an open system whose narrative is ever expanding—consumers can never assemble the whole story, can never get closure, as the culture industry constantly churns out new exemplars that are absorbed into the narrative. JRPGs, and more broadly video games, aid in this regard through DLC, which allows players to purchase additional content that potentially restructures the gaming experience. The addition of idol costumes, school costumes, and other skins in the Tales series enables players to draw from discourses external to the game and, in so doing, interact with broader themes expressed across the cultural media mix.

There are some important limitations to the cultural media mix presented here that deserve attention. The first relates to the efficacy of soft power from the perspective of the country it is exported to. Despite the ability to shape soft political narratives through the selective promotion of media, the Japanese government does not have control over what media get taken up overseas or how the discourses of and about Japan get articulated on these shores. While goth-loli or school uniforms may be expressions of kawaii in Japan, for example, the commodification of the young girls represented in them may strike different chords in different cultures. This may explain why galge and eroge,[3] other genres of games in which kawaii is prominent, make disturbing ripples when they surface in mainstream Western media.

The second matter is related to this in that, given the global flows of capital, the cultural media mix touches upon multiple international shores. It may be appropriate, then, to consider how foreign media ecologies facilitate the commodification of Japanese culture, whether this be by inscribing their own cultural fragments upon imported media to construct narratives of Japan (as a variation on Said’s Orientalism) or through how Japanese soft political discourse gets interpreted within these ecologies. The processes of localization–not only what gets localized but also how, such as their translations and the audiences these creative media are aimed at–form one potential area through which we can better understand to what extent international discourses frame Japanese creative media such as JRPGs as extensions of the country and its culture.

Works Cited

ADORNO T. W. (2001), The culture industry: Selected essays on mass culture, New York, Routledge.

AZUMA H. (2009), Otaku: Japan’s database animals (J. E. Abel & S. Kono, Trans.), Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

BARTON M. (2008), Dungeons & desktops, Wellesley, MA, A K Peters, Inc.

BEALE S. (1888, April 21). Japanese pictures, The American Architect and Building News, p. 190-191.

BOURDIEU P. (1984), Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste (R. Nice, Trans.), Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

CAPPAZUSHI (2013, May 23), Extra Credits: JRPG vs. WRPG, 2013, from <http://jrpgclub.com/community/thread-41.html?highlight=jrpg>.

CHIBA H. (2003), “Cool Japan”, Look Japan, 49 (566).

CHUANG Y. C. (2011), “Kawaii in Taiwan politics”, International Journal of Asian and Pacific Studies, 7(3), p. 1-17.

CONSALVO M. (2006), “Console video games and global corporations: Creating a hybrid culture”, New Media & Society, 8(1), p. 117-137.

COOK D. (1996), The culture industry revisited: Theodore W. Adorno on mass culture, Lanham, Maryland, Roman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

« Cool Japan » goes global (2009), Highlighting JAPAN through articles, 3(7), 21-23.

Coordinated efforts to share Japanese culture (2009), Highlighting JAPAN through articles, 3(5), p. 12-13.

Culture as a global asset (2009), Highlighting JAPAN through articles, 3(5), p. 23.

DALIOT-BUL M. (2009), “Japan Brand Strategy: The Taming of ‘Cool Japan’ and the Challenges of Cultural Planning in a Postmodern Age”, Social Science Japan Journal, 12(2), p. 247-266.

DARLEY A. (2000), Visual Digital Culture: Surface Play and Spectacle in New Media Genres, London, Routledge.

DE WYZEWA T. (1890), “Japanese Art”, The Chautauquan, XI, p. 736-740.

DOADY. (2012, November 10), “jRPG vs. wRPG (definitions)”, Retrieved 4 December, 2012, <http://www.unikgamer.com/forums/jrpg-vs-wrpg-definitions-273-p15.html>.

Extra Credits (Producer) (2012, 24 November), “Western & Japanese RPGs (Part 3)”, <http://penny-arcade.com/patv/episode/western-japanese-rpgs-part-3>.

GARDENER H. H. (1895), “Japan: Our little neighbor in the East”, In The Arena, B. O. Flower (Ed.), Vol. XI, Boston, Arena Publishing Company, pp. 176-191.

GLASSPOOL L. H. (2013), “Simulation and database society in Japanese role-playing game fandoms: Reading boys’ love « dōjinshi » online”, Transformative Works and Cultures, 12.

GLUCK C. (1985), Japan’s modern myths: ideology in the late Meiji period, Princeton, Princeton University Press.

GRAVES C. (2012), “Branding Japan: cool is not enough”, Market Leader, p. 36-38.

GYYRRO (2012, September 12). “WRPGs Vs. JRPGS: Can’t we all just get along?”, <http://www.ign.com/blogs/gyyrro/2012/09/12/wrpgs-vs-jrpgs-cant-we-all-just-get-along>.

HASEGAWA Y. (2002), “Post-identity kawaii: Commerce, gender and contemporary Japanese art” In Consuming bodies: Sex and contemporary Japanese art, F. Lloyd (Ed.), London, Reaktion Books.

HORKHEIMER M. & ADORNO T. (2002), Dialectic of enlightenment (E. Jephcott, Trans.), Stanford, Stanford University Press.

Japan’s pop culture broadens its international reach. (2009), Highlighting JAPAN through articles, 3(5), p. 10-13.

JULL J. (2001), “Games telling stories? A brief note on games and narrative”, Game studies, 1(1), <http://www.gamestudies.org/0101/juul-gts/#top>.

KATOU N. (2006), “Goodbye Godzilla, Hello Kitty”, American Interest, 2(1), p. 72-79.

KOHLER C. (2004), Power-up: How Japanese video games gave the world an extra life, Brady Games.

LOWELL P. (1887), “The soul of the Far East: Art”, The Atlantic Monthly, LX ,p. 614-624.

MCLUHAN M. (1994), Understanding media: The extensions of man, Cambridge, MIT Press.

MCVEIGH B. J. (2000), “How Hello Kitty Commodifies the Cute, Cool and Camp: ‘Consumutopia’ versus ‘Control’ in Japan”, Journal of Material Culture, 5(2), p. 225-245.

MILLER L. (2011a), “Cute Masquerade and the Pimping of Japan”, International Journal of Japanese Sociology, 20(1), p. 18-29.

——— (2011b), “Taking Girls Seriously in ‘Cool Japan’ Ideology”, Japan Studies Review, 15, p. 97-106.

Namco Bandai (2010), Tales of Graces f [Playstation 3], Tokyo, Namco Bandai Games.

Namco Bandai (2011), Tales of Xillia [Playstation 3], Tokyo, Namco Bandai Games.

NYE J. (2005), Soft power: The means to success in world politics, New York, Public Affairs.

OTSUKA E. (2010), “World and variation: The reproduction and consumption of narrative” (M. Steinberg, Trans.), In Mechademia 5: Fanthropologies, F. Lunning (Ed.), Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, p. 99-116.

POSTIGO H. (2007), “Of Mods and Modders: Chasing Down the Value of Fan-Based Digital Game Modifications”, Games and Culture, 2(4), p. 300-313.

ROSS (2012, January 29), Western RPGs vs JRPGs: My Opinion. Retrieved 2 December, 2012, <http://www.giantbomb.com/profile/ross/western-rpgs-vs-jrpgs-my-opinion/30-90553/>.

Sony Computer Entertainment Inc. (2011, May 28), “ ‘Pureisuteeshon 3’(HDD160GB)ni PS3 senyou sofutowea ‘teiruzu obu ekushiria’ wo settonishita tokubetsu genteishouhin ‘PlayStation3 TALES OF XILLIA X(kurosu) Edition’” (Playstation 3 Tales of Xillia X (Cross) edition: Special limited edition 160GB PS3 with Tales of Xillia software set), <http://www.scei.co.jp/corporate/release/110528.html>.

SOTAMAA O. (2010). “When the game is not enough: Motivations and practices among computer game modding culture”, Games and Culture: A Journal of Interactive Media, 5(3), p. 239-255.

STEINBERG M. (2012), Anime’s media mix: Franchising toys and characters in Japan, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

STORZ C. (2008), “Innovation, Institutions and Entrepreneurs: The Case of ‘Cool Japan’”, Asia Pacific Business Review, 14(3), p. 401-424.

Taking video games to the next level (2009), Highlighting JAPAN through articles, 3(7), p. 18-20.

THORNTON S. (2005), “The social logic of subcultural capital”, In The subcultures reader, K. Gelder (ed.), New York, Routledge, p. 184-192.

WEEDSTON L. (n.d.), “Western RPGs vs. Japanese RPGs”, retrieved 2 December, 2012, <http://web1.cheatcc.com/extra/westernrpgsvsjrpgs.html>.

WOLF M. J. P. (Ed.) (2002), The medium of the video game, Austin, University of Texas Press.

YANG H. (2010). Re-interpreting Japanomania: transnational media, national identity and the restyling of politics in Taiwan, PhD thesis, University of Iowa, Iowa City.

YOMOTA I. (2006), Cute Theory, Tokyo, Chikuma shobō.

Douglas Schules is an Assistant Professor at Rikkyo University in Tokyo, where his research interests focus on the intersections between the creative industries, fandom, and new media networks. He is currently working on a book about the network logic of anime fansubbing, and wishes he had more time to play JRPGs for fun.

Résumé

Malgré de fréquentes références au genre vidéoludique connu sous le nom de JRPG (Japanese role-playing game ou jeu de rôle à la japonaise) dans les travaux académiques et des fans, très peu de recherches rigoureuses furent dédiés à comprendre comment conceptualiser ce genre. Fréquemment, les JRPGs sont présenté comme une curiosité culturelle, le « J » opérant comme annexe culturel vers le genre du RPG lui-même établi et bien définit. La coordination entre gouvernement et industrie, centrale au « soft power », offre, par contre, un aperçu de la construction de ce genre en mettant l’accent sur le rôle joué par le marché au niveau de la promotion de la culture. S’inspirant de la représentation et du discours relié au sexe dans le programme Cool Japan du MEXT, cet article propose que le JRPG doit être comprit comme une partie élémentaire d’une écologie créative plus vaste qui vient à définir le Japon et sa culture outre-mer.

Mot-clés: écologie creative, Jeux de Rôles Japonais (JRPGs), kawaii, média mix, puissance douce

Notes

[1] A genre of Japanese comics marketed primarily towards pre-teen and teenage boys. The term “shōnen manga” literally means “boys’ comics”.

[2] Keroro Gunsō was first published as a shōnen manga in 1999; it later made the transition to anime in 2004 and ran until 2011. The series is episodic, and the plots revolve around the attempts of a team of alien frogs, acting as advance scouts, to weaken Earth’s defenses for full-scale military invasion. The group is led by title character Sergeant Keroro.

[3] While the terms are often used interchangeably, galge (short for “girl game”) refers to games that feature beautiful girls and often contain dating sim elements; they are sometimes called bishōjo (lit. beautiful girl) games. Eroge (short for “erotic game”), on the other hand, are games that contain sexually explicit material.