Numéro spécial, mars 2020 / Special Issue, March 2020

MARCO CARACCIOLO

Ghent University

Summary

The language of “immersion” in a fictional text lends itself to a dualistic reading that is, at best, unwelcome when attempting to think about narrative experiences ecologically. In this article, I argue for a model of narrative-audience interactions that privileges immersion as affective and temporal entanglement in stories over the containment model. I use Le quattro volte, a 2010 film by Italian director Michelangelo Frammartino, to exemplify this alternative understanding of audiences’ engagement with narrative and discuss its ramifications for recent work at the intersection of narrative theory and ecocriticism.

Keywords: Immersion, narrative, nonhuman turn, econarratology, affect

Introduction [1]

The “nonhuman turn”, in Richard Grusin’s (2015) account, is an interdisciplinary movement that seeks to go beyond worldviews and research practices that front-load human exceptionalism: instead, humanity is placed on a continuum with a broad range of nonhuman realities—from climatological patterns to biological evolution and technological devices—that interact with human societies in fundamental ways. As I suggest in Caracciolo (2019), one of the most striking points of convergence between this focus on the nonhuman and contemporary work in the philosophy of mind is their rejection of dualistic thinking. So-called “enactivist” philosophers in the wake of Francisco Varela, Evan Thompson, and Eleanor Rosch’s seminal The Embodied Mind (1991) have emphasized the “co-dependent arising” of subject and object: how the world does not pre-exist the mind, as in dualistic accounts, but emerges from patterns of embodied and affective interaction. The mind is, to quote philosopher Daniel Hutto, fundamentally “world-involving” (2012). On the other hand, thinkers affiliated with the nonhuman turn have destabilized binaries between human agency and the supposed passivity of matter (Bennett, 2010). What emerges from these debates is a notion of the fundamental entanglement—or enmeshment, in Timothy Morton’s (2010) terminology—of human subjectivity and nonhuman things and processes.

In this article, I argue that this conceptualization of the entanglement between human mind and world calls for a rethinking of the discourse of immersion: the idea, widespread in literary and media studies but also in discussions outside of academia, that a certain state of focused attention when engaging with narrative can be described as being “immersed” in a book or film. This rethinking is necessary to rule out an exclusively spatial reading of the phenomenon of immersion. Etymologically, immersion evokes the image of a solid object being plunged into a liquid. This spatial scenario can be understood dualistically: while the solid is surrounded by the fluid, the two remain fundamentally separate. When extended metaphorically to readers’ experience of fictional texts, this way of conceptualizing immersion can bring in a dichotomy between “immersive” and “non-immersive” ways of reading. In a chapter on metafiction, Merja Polvinen draws attention to how self-conscious writers “question the in/out model of spatial imagination in fiction that we have relied on for so long” (2016, p. 24). Polvinen targets this model of the spatial imagination because, she argues, it is bound up with a false dichotomy between awareness of fictionality and imaginative engagement with fiction—as if audiences were forced to choose between paying attention to the characters, events, and situations represented by fictional narrative and appreciating the artistry of their representation. My approach to immersion has different goals from Polvinen’s, but it stems from similar concerns about how the term can bias—more or less subtly—our thinking and talking about narrative experiences. I structure my critique around two points. First, the language of immersion aligns with what cognitive linguists in Lakoff and Johnson’s (1980) wake would call a “container” image schema: the notion that narratives are spatially bounded and that audience members can be positioned either inside or outside them. This conception has the unwelcome effect of separating, dualistically, narratives from readers’ consciousness, as well as narrative experiences from everyday reality. Second, through its inherently spatial nature, the discourse of immersion tends to play down the enmeshment of temporality, spatiality, and emotion in narrative experiences—how temporal patterns structure our engagement with narrative, and how the nature of these patterns is affective through and through.

These points require full consideration as literary and media studies explore the interplay between narrative and the environmental imagination. In her seminal The Storyworld Accord (2015), Erin James outlines an innovative research program at the intersection of ecocriticism, narrative theory, and cognitive approaches to literature. Immersion is the conceptual cornerstone of James’s “econarratology”:

Econarratological readings of narrative storyworlds, via their analysis of the textual cues that aid the immersion of readers into subjective spaces, times, and experiences, help us appreciate the fact that aesthetic transformations of the real really do stand to reshape individual and collective environmental imaginations. That reshaping is an essential role that literature can play in protecting the earth. (2015, p. 39)

This is a bold articulation of the link between the imaginative and emotional effects of narrative and its broader cultural function; the possibility of immersion is central to this kind of reasoning: narrative literature will realize its “essential role” of “protecting the earth” to the extent that it succeeds in eliciting a state of immersion in readers. Immersion is here described in terms of a “deictic shift” (cf. James, 2015, p. xi) from the reader’s physical surroundings to an imaginary domain that James, like most narrative theorists, conceptualizes as a textual “world” or “storyworld”.

My core claim in this article is that an ecologically informed understanding of audiences’ engagement with narrative has to move beyond the spatial isolation of storyworlds, embracing the temporally and affectively patterned nature of text-audience encounters. This could be achieved by reconceptualizing immersion not as containment in a text but as a form of entanglement with it. In media and game studies, scholars such as Gordon Calleja (2011) have already explored the multifaceted nature of immersion. For Calleja, immersion in video games involves six dimensions, only one of which is predominantly spatial. My account of immersion as entanglement focuses on Calleja’s affective dimension, which includes bodily sensations and feelings generated during the engagement with a narrative artifact. By addressing the spatial bias in immersion discourse in narrative theory (as opposed to Calleja’s home field of game studies), I seek to bridge the gap between the discussion of narrative experiences and contemporary debates on the nonhuman. Given that the notion of human-nonhuman entanglement is central to these debates in ecocriticism (e.g., Iovino and Oppermann, 2012), what kind of reading or viewing practices—and what theoretical models—are best suited to bring out this entanglement in narrative form? I argue below that a principled understanding of narrative engagement requires, first, distancing ourselves from the container image schema not just for narrative experiences but also for human-nonhuman interactions; and, second, it requires fully considering the way in which temporally patterned affect feeds into audiences’ interactions with narrative. Put baldly, immersive narrative experiences disrupt the conceptual distinction between a human subject and a physical artifact (the text) in a way that resonates deeply with insights into the imbrication of human and nonhuman realities within the nonhuman turn. The vehicle of this blurring of boundaries is the affective dimension of audiences’ temporally extended engagement with stories.

An important precedent in acknowledging the centrality of affective responses to narrative is Alexa Weik von Mossner’s Affective Ecologies (2017). Through its confrontation with embodied cognitive science, this book makes a key step towards a more comprehensive understanding of immersion, one whose ramifications for the environmental humanities Weik von Mossner charts with particular lucidity. My discussion in this article develops Weik von Mossner’s interest in the nexus of embodiment, affect, and the narrative imagination of the nonhuman. I use as case study a 2010 film by Italian director Michelangelo Frammartino. The film is titled Le quattro volte, translated into English as The Four Times (but we’ll see that the title can also mean “the four turns”). Frammartino’s film is set in and around a medieval town perched on the rural hills of Calabria, in the southern tip of the Italian peninsula. It is a slow, philosophical film, whose narrative weaves together a human character—an old goatherd—his goats, as well as the material world in which they are embedded. Human dialogue is scarce and mostly inaudible; goat bleats, dog barks, and rustling leaves take center stage. The film foregrounds the cyclical nature of life: we first experience the daily routine of the goatherd, who appears to be seriously ill; after the goatherd dies, a goat is born; the goat finds shelter under a fir tree, which is later felled and turned into a greasy pole, becoming the main attraction of a country festival; finally, wood from the tree is turned into charcoal. This fourfold structure suggests ancient notions of metempsychosis or Buddhist reincarnation; but the film is remarkably agnostic and evokes the interconnectedness of life through aesthetic form rather than religious belief. It is because of this formal interest in human-nonhuman entanglement that I single out Le quattro volte as a test bed for the reappraisal of immersion I want to propose in this article. I will thus explore how the film pushes back against the container image schema, problematizing claims about the viewers’ spatial position inside or outside the storyworld; and how the film uses affective patterning to entangle the audience in the narrative. Before that, however, I will explain why the concept of immersion, as it is used in narrative theory, lends itself to a dualistic reading.

Coming to Terms with Mixed Metaphors

One of the most sustained account of immersion in narrative theory can be found in Marie-Laure Ryan’s Narrative as Virtual Reality (2001). I won’t attempt to summarize the details of Ryan’s discussion; instead, I focus on a key passage in which Ryan highlights the metaphorical nature of the term “immersion”:

The notion of reading as immersive experience is based on a premise so frequently invoked in literary criticism that we tend to forget its metaphorical nature. For immersion to take place, the text must offer an expanse to be immersed within, and this expanse, in a blatantly mixed metaphor, is not an ocean but a textual world. (2001, p. 90)

Here Ryan discusses the metaphorical shift from immersion in an ocean to textual immersion. But she does not acknowledge the fact that “textual world” is in itself a metaphor, and that it implicates a particular image schema: that of the text as a spatial container into which readers may enter, or that they may refuse to enter. “Image schema” is a term used in cognitive linguistics (see, e.g., Hampe and Grady, 2005) to refer to proto-concepts based on perceptual templates or Gestalten. [2] Examples include path, balance, or container itself—all patterns derived from embodied experience but frequently employed to think and talk about abstract scenarios, often via metaphorical language. In the phrase “the balance of power between two nations”, for instance, the physical experience of equilibrium is invoked to conceptualize a much more abstract notion of economic or military power. In the case of immersion, the abstract process that is understood schematically is readers’ imaginative engagement with a text, which is equated with physical immersion in a containing medium (such as the ocean).

The problem is, of course, that texts are not containers, not even if we embrace the notion of storyworlds, or fictional words, to specify the target of the immersion, as Ryan and many narrative theorists do. Indeed, the notion of storyworlds, introduced by David Herman in Story Logic (2002), has become so entrenched in narrative theory that one of the field’s main journals (Storyworlds) is titled after it. But the “text as world” metaphor has not gone unchallenged. An effective critique can be found in a chapter by Richard Walsh (2017) that builds on his earlier The Rhetoric of Fictionality (2007). Walsh scrutinizes the ontological commitments that may creep in when we see texts as worlds: taken at face value, the metaphor implies that the narrated reality, like a world, must be ontologically complete and separate from the domain of everyday perception and social interaction. I have already discussed Walsh’s critique of storyworlds elsewhere (Caracciolo, 2018b), pointing out that the notion of worlds is perhaps not fundamentally flawed, but it has to be dramatically reconfigured to align with models derived from psychological research on narrative reading: the mental models we build in making sense of narrative are not stable ontological domains; they are ad-hoc, dynamic constructs that develop according to a predominantly affective logic.

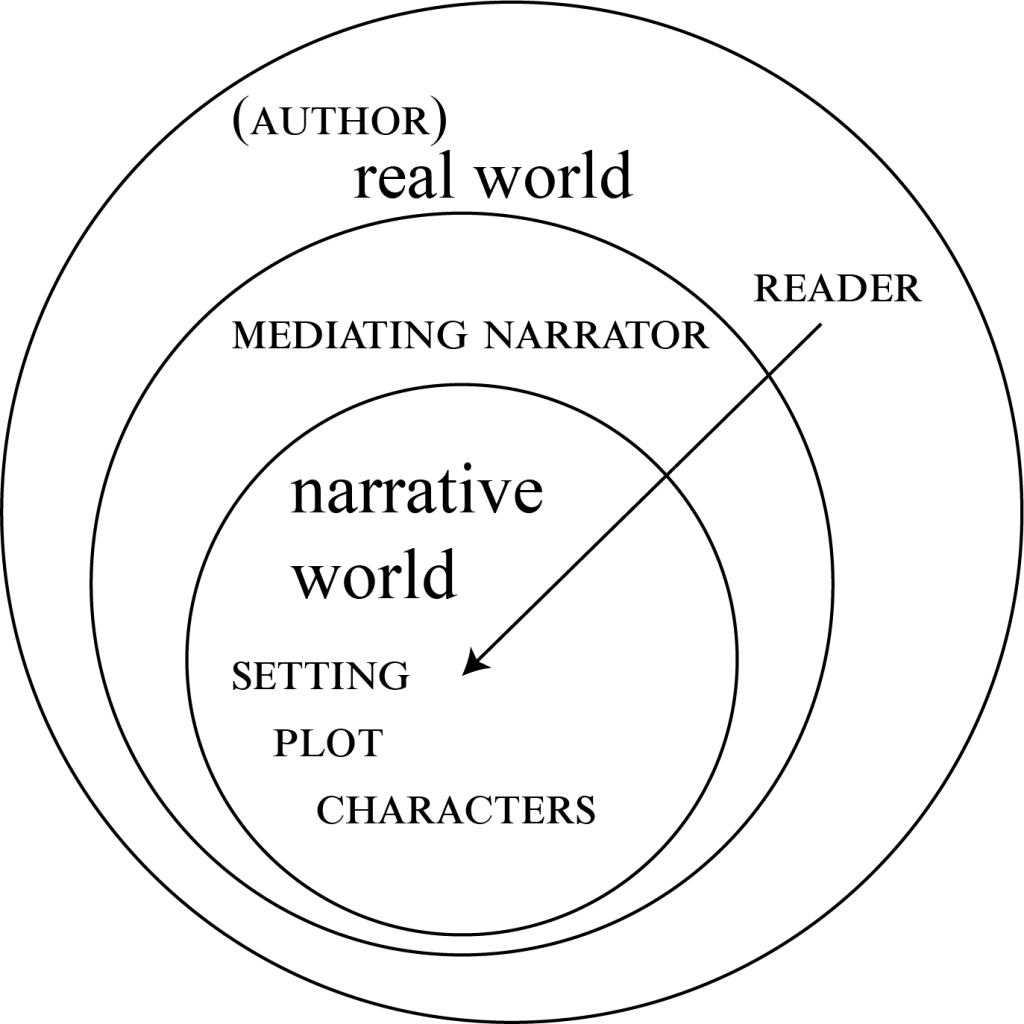

This point has important consequences for theories of immersion. Current work on immersion in cognitive approaches to narrative capitalizes on the spatial nature of the metaphor. For instance, Hilary Dannenberg sees immersion as the crossing of an ontological boundary—that of the fictional world. Dannenberg (2008, p. 24) uses the diagram in Figure 1 to represent the reader’s “journey” from the real world to the narrative world—where the multiple circles suggest separation but also containment. Accordingly, Dannenberg opposes immersion to the readerly “expulsion” caused by metafictional narratives: “The shock tactics of metafiction bring about expulsion, and the reader is forcefully ejected from her mental sojourn within the narrative world and jolted back to her own ontological level” (2008, p. 23). This statement is a clear illustration of how easy it is for accounts of immersion to tip over into the dualistic language of being “inside” or “outside” a container-like text.

Contrast Dannenberg’s model with Calleja’s already mentioned account, which focuses on the multidimensional nature of immersion in video games. In game studies, a nuanced understanding of immersion has been advanced by many commentators (see, e.g., Arsenault). In literary studies, however, immersion is still largely bound up with spatial metaphors that suggest a physical relocation of the reader from the actual to a fictional world. Among these spatial metaphors are Richard Gerrig’s (1993) “transportation” and Ryan’s (2001) own “recentering,” which also figures in Werner Wolf’s (2004, p. 325) definition of “aesthetic illusion” (a concept closely related to immersion). [3] Even when space is not foregrounded explicitly, as in Jean-Marie Schaeffer and Ioana Vultur’s (2005) discussion, it enters the picture through the “text as world” metaphor, which is—as argued by Walsh (2017)—primarily spatial: worlds are spatial domains that remain relatively stable despite changes occurring over time.

This does not mean that literary scholars are unaware of the non-spatial dimensions of immersion, of course. For instance, Anežka Kuzmičová’s (2012) cognitively inspired account of “presence” in reading acknowledges that the experience of being physically part of a fictional space is an important factor in narrative engagements. But Kuzmičová also points out that immersion is a multifaceted concept, and that spatial presence is only one of its components, along with “affective appraisal […] emotional response […], suspense […], or rhythm and flow of inner speech” (2012, p. 24). Yet, when spatial metaphors and especially metaphors of relocation and containment become too rigid (as they do in Dannenberg’s discussion), the risk is that the discourse of immersion will shortchange the temporal and affective nature of audience’s entanglement with narrative. This is the risk I want to identify and warn against in this article as I develop a concept of immersion attuned to human-nonhuman entanglements in narrative audiences. My suggestion is to factor in the role of embodied-affective experience in responding immersively not just to individual elements of the narrative (such as spaces and characters) but to the aesthetic form of narrative itself. This is where the model of immersion as corporeal entanglement comes into play. Entanglement is related to image schemata discussed by cognitive linguists under the rubric of “linkage” and “cycle” (see Evans and Green, 2006, p. 190), and is thus opposed to the closure and in-out logic of containment and relocation: in entanglement, the attention of audience members becomes deeply interlinked with the stylistic and narrative form of a story through cycles of imaginative and affective engagement. I will unpack this idea in the next two sections, using Le quattro volte as a guide text.

Beyond Containment

Metaphors of physical containment and relocation position the audience as interacting with narrative across an ontological divide that may be bridged—in immersion—but whose existence remains an underlying assumption of the model: from this perspective, the fundamental separateness of the real and the fictional, and of the audience’s subjectivity and the narrative, is preserved.

This is not the only available conceptualization of immersion, however. I’m interested in the possibilities of thinking about narrative as an affective and embodied experience that entangles audiences members with a certain perspective on the world. [4] From this standpoint, which is inspired by enactivist philosophy (Varela, Thompson, and Rosch, 1991), there is no need for a proliferation of worlds: narrative is always about the real world, even if this aboutness tends to involve a great deal of indirectness. Stories can and do represent states of affairs that are non-actual and even, in some cases, technologically or physically impossible (think science fiction or fairy tales). But the stakes of this representation are always determined by affective, cultural, or ethical values that are grounded in social interactions and practices. To put the same point more succinctly, every narrative is entangled in a web of assumptions about reality (see Gibson, 2007; Caracciolo, 2014).

This does not mean that narrative is bound to replicate those assumptions, of course. In an ecocritical context, Hubert Zapf (2001) has provided us with sophisticated concepts to discuss literary narrative’s active role in questioning and bridging cultural values. The point is that narrative, including fictional narrative, is always embedded in, and never separate from, the real world: the container schema and the language of “transportation” and “recentering” risk creating an artificial barrier between readers’ everyday life and their narrative experiences. Instead, we should shift the focus from containment and relocation to the incorporation of narrative as a fundamentally entangled metaphor that foregrounds the embodiment and situatedness of text-audience encounters. [5]

Of course, I am aware that some audience members enjoy that artificial separation: the discourse of immersion can dovetail with an escapist or hedonistic way of engaging with narrative, where stories provide shelter from the worries of the quotidian (see Victor Nell’s classic study of escapism in pleasure reading; Nell, 1988). But this practice is, it seems to me, a problematic position that should be resisted—especially from an ecocritical perspective. Instead, we should foster practices of narrative engagement that reject simplistic notions of immersion-as-containment and call for a recognition of narrative’s participation in networks of human-nonhuman interaction. The binary between the real and the fictional in traditional accounts of immersion can be neatly mapped onto the binary between human subjectivity and nonhuman animals, things, and processes. Both binaries should be questioned if we approach immersion ecocritically—and this, I claim, is what a film like Le quattro volte encourages us to do.

The film repeatedly foregrounds the impossibility of containing the natural. We see the goatherd—effectively, the film’s only human character—collecting snails and placing them in a large pot: the goal, we infer, is to purge them until they are edible. A brick weighs down the lid to keep the snails from escaping. But when the man returns home, he finds the snails all over the kitchen table; he patiently collects them and puts them back in the pot. In a later scene, a long static shot displays the road winding off one of the town gates, with the goatherd’s house in front and the enclosure where the goats are kept on the left-hand side. A pickup truck is parked on an incline on the right (see Figure 2). In this scene, a particularly fractious herding dog unexpectedly removes the wheel chock that keeps the truck in place, so that the vehicle rolls backward, smashing into the fence and thus freeing the goats. The animals then flood the road and enter the goatherd’s apartment. One of them, standing on the kitchen table (see Figure 3), intentionally topples the pot with the captive snails.

The pot and the goat pen evoke the container image schema—they are images of the human desire to contain and master the nonhuman world. Frammartino’s narrative highlights the autonomous agency of animals that sabotage the human world order. But this destabilization of containment goes hand in hand with the interpretive stance promoted by the film as a whole. At one level, Frammartino’s film explores material life in a rural community in Calabria—from religious practices to the traditional method of charcoal-making—so as to blur the boundary between documentary and fiction film: any strict ontological separation between reality and the fictional events of the narrative is defused. Even more importantly, Frammartino unsettles the idea that film narrative is driven by human interests and goals: through the dog’s or the goats’ apparently spontaneous mischief, the progression of the film is closely coupled with the agency of nonhuman animals. We may wonder how long Frammartino had to shoot to capture the dog removing the wheel chock, or the goat toppling the snail pot in that nonchalant way. But in considering those questions, we are simultaneously in the film’s “world” and outside it, reflecting on the conditions of its production. The narrative thus conveys a sense of entanglement between the human world, including the practice and technology of film, and the foregrounded nonhuman agency. We will see in the next section that this entanglement is closely linked to the film’s formal articulation of temporality.

Affective Form and Temporal Patterning

The latent spatiality of much immersion discourse should not overshadow the role that temporal dynamics play in narrative engagement. After all, the experience of physical immersion itself—when diving, for instance—is patterned in temporal and affective terms. How do we factor in such patterns in developing an account of immersion as entanglement? The relationship between narrativity and temporality is one of the tenets of narrative theory, and has been discussed by such influential commentators as Paul Ricoeur and Harald Weinrich (Ricoeur, 1984; Weinrich, 1985; see Fludernik, 2005). What recent work in cognitive literary studies adds to the picture is that this relationship between time and narrative is fundamentally affective. Narrative is not just the representation of a temporal sequence, it involves the affective articulation of time. Philosopher David Velleman puts this point as follows:

A story […] enables its audience to assimilate events, not to familiar patterns of how things happen, but rather to familiar patterns of how things feel. These patterns are not themselves stored in discursive form, as scenarios or stories: they are stored rather in experiential, proprioceptive, and kinesthetic memory—as we might say, in the muscle-memory of the heart. (2003, p. 19)

The key word here is “patterns”: narratives build and elaborate on forms of affective experience, which underlie the representational content of narrative—“how things happen”—and constitute story structure. At a basic level, the macro-form of narrative or its “cadence” (as Velleman calls it) is “the arousal and resolution of affect” (2003, p. 13). But a large number of variations on this basic emotional cadence are possible.

Andrew Reagan and his collaborators (Reagan et al., 2016) have analyzed emotional language in a large corpus of narratives drawn from Project Gutenberg. They processed these narratives with a computer algorithm capable of sentiment analysis—that is, of identifying the patterning of emotion in each of these stories. The analysis shows that narratives tend to be organized around six “basic shapes”, in Reagan and colleagues’ terminology, depending on the affective trajectory traced by different genres: for instance, a constant rise (in prototypical “rags to riches” stories), or a steady downward trajectory (in tragedy), or a sequence of rise, fall, and rise. Narrative form (in this case, genre) is aligned with emotional dynamics that develop in the course of the narrative, as Reagan et al.’s sentiment analysis suggests, and thus unfold during the audience’s temporal engagement with the text. The take-away is, from my perspective, less Reagan’s typology than the suggestion that narrative is organized according to a recognizable affective-temporal logic. This logic is an elaboration of Velleman’s “arousal and resolution of affect”.

We could go even further, analyzing the emotional patterning of individual narratives and how it involves an interplay of what film theorist Ed Tan (1996; Visch, Tan, and Molenaar, 2010) calls Artifact and Fictional World emotions: the former are directed at formal features of the narrative text, the latter at the represented characters and situations. The coherence and novelty of the affective pattern that results from the combination of Artifact and Fictional World emotions are a crucial factor in producing the state of attention that we refer to as “immersion”. Again, the language of spatial containment is less useful than a language of entanglement: this affective pattern implicates readers or viewers in the narrative; it activates what Velleman calls the audience’s “muscle-memory of the heart” and prompts them to resonate with the text’s formal-temporal patterning. This affective resonance breaks down distinctions between the audience’s subjectivity and the presumed objectivity of the fictional world: it does not simply draw them into a pre-existing, container-like world but asks them to bring this world forth—to use enactivist terminology—with their bodies. It thus becomes impossible to draw a sharp line between spatiality and temporality: the feeling of spatial presence in an imaginary reality is intimately connected to the temporally patterned affect that enfolds audience members into a narrative. Not all narratives entangle readers and viewers to the same extent, of course. The audience’s predispositions play an important role, but so does the text’s capacity to generate a distinctive affective cadence.

Le quattro volte offers a particularly convincing example of affective form. As the title suggests, the film has four parts, each with its own protagonist: a goatherd, a young goat or kid, a fir tree, and charcoal. The passage of time is foregrounded—for instance, in a sequence that shows the fir tree silhouetted against a winter landscape, then the close-up of a tree trunk, then the fir tree surrounded by lush vegetation. The film’s temporality is articulated not by way of explicit causal linkage, but through two formal devices, which bring the film’s four parts together: a focused affective pace and a carefully orchestrated movement from the human to the animal domain (the goats) to the vegetal (the fir tree) and finally to the mineral and inanimate (the charcoal).

The pace of the narrative can be described as stately and contemplative. Its main effect is to flatten differences between, for instance, a herd of vivacious goats and the religious practices of a rural community in southern Italy. The film progressively distances audience members from the human-scale world of everyday interaction, inviting them to perceive similarities across the human-nonhuman divide. However, that aesthetic distance is never devoid of compassion: Frammartino explores the fragility of human and nonhuman animals vis-à-vis a vast nonhuman world. Thus, the experience of watching Le quattro volte cannot be accounted for in terms of a simple opposition between immersion and expulsion: as we become entangled in the affective pace of the film, we are also released from an anthropocentric view of the world.

This is the formal movement I’ve alluded to: the film starts with a human protagonist—the goatherd—but ends with a nonhuman one—the charcoal. The narrative shifts along what philosophers have discussed, following Plato and Aristotle, as the “great chain of being” (Lovejoy, 2001). However, Frammartino’s film resists the hierarchical organization of that chain, the idea that intrinsic value decreases as we move from the human to the nonhuman. This resistance is closely tied to the film’s aesthetics: Frammartino’s style suggests, pointedly, that there is aesthetic texture and value throughout the chain. This interest in the textural complexity of the nonhuman world is demonstrated by frequent close-ups—for instance, of charcoal pieces or a tree trunk. The linear movement from the human to the nonhuman is also complicated by the film’s circular form: charcoal making was already shown in the film’s preamble, but at the end of the film we approach it in a way that is much more attuned to the nonhuman world, because we are closely familiar with the material history of the wood that is being burned. The image schema that emerges is not the container but the cycle: the film’s repeated shifts from one domain of reality to another open up a shared, communal space between the human and the nonhuman—almost like metempsychosis, but minus the mind-body dualism that metempsychosis seems to imply. In other words, what the film performs is not a negatively connoted “descent” into the nonhuman, but a circular movement that displays the ecological interdependency of human societies and nonhuman things and processes.

The human, the film’s starting point and the home field of narrative itself (see Caracciolo, 2018a), is finally reabsorbed into a formal pattern that destabilizes the human-nonhuman binary. Audience members are invited to experience this formal pattern, in their bodies, through affective pace. It is perhaps not too far-fetched to conjecture that this embodied substrate of the narrative is implied by the title, which translates as both “the four times” and “the four turns”, in the sense of the physical action of turning. Read in this way, the title captures the film’s affective organization of time and, concurrently, the marked embodied quality of the conceptual transitions it reveals.

Conclusion

My goal in this article was to push back against a certain understanding of the experience we refer to as “immersion”, one that capitalizes on spatial metaphors, and particularly metaphors of spatial containment in and relocation to storyworlds. I do not claim that all narrative scholars subscribe to a predominantly spatial conception of immersion. Yet spatial metaphors may still implicitly bias our ways of thinking about narrative experiences, suggesting a dualistic separation between subjectivity and narrative, or the real world and fictional “worlds”. This is the risk I tried to address in these pages. To overcome this bias, I proposed conceptualizing the experience of immersion as affective entanglement with story. The result of this entanglement is a heightening of attention that is modulated by stylistic and narrative form, and that transcends a mere sense of spatial containment in a world: rather, in immersive experiences the audience’s imagination resonates with a material artifact in a way that destabilizes the text-world dichotomy.

Once this definition of immersion is in place, we can see how the notion of entanglement—and the experience it captures—can be used to probe another kind of entanglement: namely, humanity’s deep imbrication with the nonhuman world. Understood in this way, immersion is a state of consciousness that troubles dualistic binaries, confronting audience members with their fundamental interrelation with the material and nonhuman world. The concept of entanglement echoes recent work within the nonhuman turn that confronts the realities of climate change and the Anthropocene. For instance, it is one of the core concepts of Karen Barad’s (2007) quantum physics-inspired account of what she calls the “intra-action” of matter and subjectivity. Similarly, “entangled humanism” is the term chosen by William Connolly for the ambitious political philosophy he outlines in Facing the Planetary (2017). At the same time, entanglement ties in with an enactivist understanding of how minds bring forth or enact a world: reality does not pre-exist the mind, but is enacted through patterns of sensorimotor, embodied activity, at the level of perception and basic emotions (Noë, 2004; Hutto and Myin, 2012); and through patterns of intersubjective coordination, at the level of more advanced, socio-culturally acquired skills (De Jaegher and Di Paolo, 2007). The nonhuman turn and enactivist philosophy thus converge on the idea that the mind is deeply entangled with the world. Frammartino’s Le quattro volte brings out this entanglement by fostering a specific immersive mode of spectatorship: one that detaches spectators from the human-centered world of prototypical narratives and asks them to confront a tapestry of nonhuman characters and events. The vehicle of this immersion is affect: the fourfold temporal structure of the film creates a contemplative pace, which gradually acclimatizes the spectator to the slow twists and turns, or “volte”, of the nonhuman world. Clearly, this is only the beginning of a cross-fertilization of the mind sciences and ecocriticism—a prospect rich in societal implications. As I argued in this article, careful reflection on narrative experience and the concepts and metaphors we use to talk about it is key to this interdisciplinary encounter.

References

Arsenault, D. (2005), “Dark Waters: Spotlight on Immersion”, in Game On North America 2005 International Conference Proceedings, Ghent, Eurosis, pp. 50–52.

Balint, J., and Tan, E. S. (2015), “‘It Feels Like There Are Hooks Inside My Chest’: The Construction of Narrative Absorption Experiences Using Image Schemata”, Projections, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 63–88.

Barad, K. (2007), Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning, Durham, Duke University Press.

Bennett, J. (2010), Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things, Durham, Duke University Press.

Calleja, G. (2011), In-Game: From Immersion to Incorporation, Cambridge, MA, MIT Press.

Caracciolo, M. (2014), The Experientiality of Narrative: An Enactivist Approach, Berlin, De Gruyter.

——— (2018a), “Posthuman Narration as a Test Bed for Experientiality: The Case of Kurt Vonnegut’s Galápagos”, Partial Answers, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 303–14.

——— (2018b), “Ungrounding Fictional Worlds: An Enactivist Perspective on the ‘Worldlikeness’ of Fiction”, in Bell, A. and Ryan, M.-L. (eds.), Possible Worlds Theory and Contemporary Narratology, Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, pp. 113–31.

——— (2019), “Islands of Mind and Matter: Challenging Dualism in J. G. Ballard’s ‘The Terminal Beach’ and The Chinese Room’s Dear Esther”, CounterText, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 341–61.CONNOLLY, W. E. (2017), Facing the Planetary: Entangled Humanism and the Politics of Swarming, Durham, Duke University Press.

Dannenberg, H. P. (2008), Coincidence and Counterfactuality: Plotting Time and Space in Narrative Fiction, Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press.

De Jaegher, H., and Di Paolo, E. A. (2007) “Participatory Sense-Making: An Enactive Approach to Social Cognition”, Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 485–507.

Evans, V., and Green, M. (2006), Cognitive Linguistics: An Introduction, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Fludernik, M. (2005), “Time in Narrative”, in Herman, D., Jahn, M. and Ryan, M.-L. (eds.), Routledge Encyclopedia of Narrative Theory, London, Routledge, pp. 608–612.

Gerrig, R. J. (1993), Experiencing Narrative Worlds: On the Psychological Activities of Reading, New Haven, Yale University Press.

Gibson, J. (2007), Fiction and the Weave of Life, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Grusin, R., ed. (2015), The Nonhuman Turn, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

Hampe, B., and Grady, J. E. (2005), From Perception to Meaning: Image Schemas in Cognitive Linguistics, Berlin, De Gruyter.

Herman, D. (2002), Story Logic: Problems and Possibilities of Narrative, Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press.

Hutto, D. D. (2012), “Exposing the Background: Deep and Local”, in Radman, Z.(ed.), Knowing without Thinking: Mind, Action, Cognition and the Phenomenon of the Background, Basingstoke, Palgrave, pp. 37–56.

Hutto, D. D., and Myin, N, E. (2012), Radicalizing Enactivism: Basic Minds without Content, Cambridge, MA, MIT Press.

Iovino, S., and Oppermann, S. (2012), “Theorizing Material Ecocriticism: A Diptych”, Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 448–75.

James, E. (2015), The Storyworld Accord: Econarratology and Postcolonial Narratives, Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press.

Kuzmičová, A. (2012), “Presence in the Reading of Literary Narrative: A Case for Motor Enactment”, Semiotica, vol. 189, no. 1/4, pp. 23–48.

Lakoff, G., and Johnson, M. (1980), Metaphors We Live By, Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Lovejoy, A. O. (2001), The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press.

Morton, T. (2010), The Ecological Thought, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press.

Neimanis, A., and Walker, R. L. (2014), “Weathering: Climate Change and the ‘Thick Time’ of Transcorporeality”, Hypatia, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 558–75.

Nell, V. (1988), Lost in a Book: The Psychology of Reading for Pleasure, New Haven, Yale University Press.

Noë, A. (2004), Action in Perception, Cambridge, MA, MIT Press.

Polvinen, M. (2016), “Enactive Perception and Fictional Worlds”, in Garratt, P.(ed.), The Cognitive Humanities: Embodied Mind in Literature and Culture, London, Palgrave, pp. 19–34.

Reagan, A. J., Mitchell, L., Kiley, D., Danforth, C. M. and Sheridan Dodds, P. (2016), “The Emotional Arcs of Stories Are Dominated by Six Basic Shapes”, in EPJ Data Science, vol. 5, no. 31, https://doi.org/10.1140/epjds/s13688-016-0093-1.

Ricoeur, P. (1984), Time and Narrative: Volume 1, Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Ryan, M.-L. (2001), Narrative as Virtual Reality: Immersion and Interactivity in Literature and Electronic Media, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press.

Schaeffer, J. M., and Vultur, I. (2005), “Immersion”, in Herman, D., Jahn, M. and Ryan, M.-L. (eds.), Routledge Encyclopedia of Narrative Theory, London, Routledge, pp. 237–39.

Tan, E. S. (1996), Emotion and the Structure of Narrative Film: Film as an Emotion Machine, Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum.

Varela, F. J., Thompson, E., and Rosch, E. (1991), The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience, Cambridge, MA, MIT Press.

Velleman, J. D. (2003), “Narrative Explanation”, The Philosophical Review, vol. 112, no. 1, pp. 1–25.

Visch, V. T., Tan, E. S., and Molenaar, D. (2010), “The Emotional and Cognitive Effect of Immersion in Film Viewing”, Cognition and Emotion, vol. 24, no. 8, pp. 1439–45.

Walsh, R. (2007), The Rhetoric of Fictionality: Narrative Theory and the Idea of Fiction, Columbus, Ohio State University Press.

——— (2017), “Beyond Fictional Worlds: Narrative and Spatial Cognition”, in Hansen, P. K., Pier, J., Roussin, P., and Schmid, W.(eds.), Emerging Vectors of Narratology, Berlin, De Gruyter, pp. 461–78.

Weik Von Mossner, A. (2017), Affective Ecologies: Empathy, Emotion, and Environmental Narrative, Columbus, Ohio State University Press.

Weinrich, H. (1985), Tempus: Besprochene und erzählte Welt, Stuttgart, Kohlhammer.

Wolf, W. (2004), “Aesthetic Illusion as an Effect of Fiction”, Style, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 325–51.

Zapf, H. (2001), “Literature as Cultural Ecology: Notes Towards a Functional Theory of Imaginative Texts, with Examples from American Literature”, REAL – Yearbook of Research in English and American Literature, vol. 17, pp. 85–100.

Marco Caracciolo is Associate Professor of English and Literary Theory at Ghent University in Belgium, where he leads the ERC Starting Grant project “Narrating the Mesh” (NARMESH). Marco’s work explores the phenomenology of narrative, or the structure of the experiences afforded by literary fiction and other narrative media. Currently, his work investigates narrative strategies for figuring humanity’s entanglement with a more-than-human world in times of ecological crisis. He is the author of three books, including most recently Strange Narrators in Contemporary Fiction: Explorations in Readers’ Engagement with Characters (University of Nebraska Press, 2016).

[1] Research for this article has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement No 714166).

[2] See also Evans and Green (2006, p. 190) for an inventory of image schemata.

[3] It is worth noting that spatial metaphors are also widely used by lay audiences to describe immersive experiences. See Bálint and Tan (2015).

[4] The upshot of this idea is that immersion as entanglement is not limited to audiences’ responses to fiction but can be elicited by non-fictional narratives as well, provided that the presentation is affectively and formally sophisticated. However, this line of thinking falls beyond the scope of this article.

[5] Incorporation is, of course, a centerpiece of Calleja’s (2011) model of immersion. In a very different context, Astrida Neimanis and Rachel Loewen Walker articulate an “entangled” notion of the body that puts human societies on a continuum with the nonhuman world (a position that Neimanis and Walker refer to as “weathering”). Interestingly for our purposes, Neimanis and Walker also privilege incorporation over spatial notions of containment: “Nuanced this way—as incorporation that engenders differences that matter, rather than contiguity or immersion—transcorporeal relations reveal the enactments of weathering” (2014, p. 566).